Moral Essays (also known as Epistles to Several Persons) is a series of four poems on ethical subjects by Alexander Pope, published between 1731 and 1735.

Moral Essays (also known as Epistles to Several Persons) is a series of four poems on ethical subjects by Alexander Pope, published between 1731 and 1735.

The four poems were first published under the name Moral Essays by William Warburton (Pope’s literary executor) in 1751, not in the chronological order in which they were first written, but in the order:

Along with An Essay on Man , which was written during the same period, they were inspired by Pope’s affection for Bolingbroke, and it seems (from what Pope told his friend Jonathan Swift) that he intended the entire work to be part of his ‘opus magnum’, a ‘system of ethics in the Horatian way’. [1] It was Pope himself who described them as Epistles to Several Persons.

The subtitle of this poem, initially Of False Taste, was changed to Of the Use of Riches. It covers the subject of the use of wealth in both a tasteless and a proper manner, and particularly deals with landscaping, gardens and architecture, specific interests of Lord Burlington, who had been a friend of Pope since about 1715. [2]

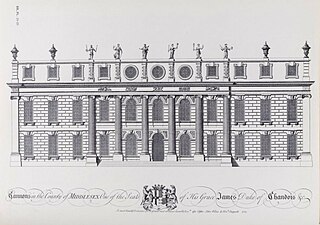

The key to good taste when designing an estate, Pope says, is to ‘Consult the Genius of the Place in all’ (l. 57), a precept followed by Bathurst and others, but not by the superficial, ostentatious landowner identified as ‘Timon’. Although his description of Timon’s villa is a synthesis of details from different sites, it was soon widely criticised as an attack on the Berkshire estate of the Duke of Chandos, damaging Pope’s own reputation and career. This also put an end to any relationship between him and Sir Robert Walpole, Bolingbroke’s main political opponent. [2]

Like Burlington, this epistle is subtitled Of the Use of Riches. It deals with the use of money, arguing that both greedy and wasteful people misapply it, and so derive no happiness from it, though its target is more the rising commercial class, rather than the ruling aristocracy as in Burlington. [2] Pope presents a series of satirical portraits of wasteful or parsimonious characters, but in particular he describes ‘The Man of Ross’ (John Kyrle), who was generous with his wealth, and ‘Sir Balaam’, whose riches lead him into penury.

The Man of Ross had given generously to the town of Ross-on-Wye, though Pope may have exaggerated his benevolence. After suggesting that Bathurst might ask what vast means he had to achieve all this, the poet replies: ‘Of debts and taxes, wife and children clear, This man possest – five hundred pounds a year.’ (ll. 275-80) Though this is disclosed as if some remarkable achievement, that amount might be well into six figures in current terms, and at a time when workmen’s wages were very meagre. Nonetheless, the point was made.

Sir Balaam, by contrast, is a religious, sober (but parsimonious) tradesman of the City of London where ‘London’s column, pointing at the skies Like a tall bully, lifts its head and lyes’. (ll. 339-40) - Pope’s famous attack on the blame falsely cast on Catholics for starting the Great Fire of London by the inscription on The Monument.

Balaam in the Bible was corrupted from his pious conduct by bribery, as Pope’s readers would have known, [2] and so Sir Balaam, having risen to great wealth and success, subsequently overreaches himself, commits various offences and crimes, and is eventually hanged. The poem’s conclusion requires no moral additional to: ‘The Devil and the King divide the prize, And sad Sir Balaam curses God and dies.’ (ll. 401-2)

Addressing this poem to Viscount Cobham, Pope considers the knowledge and personality of various people, discussing the difficulty in reading the character of men. He visited Cobham’s house at Stowe in the summer of 1733, shortly after its owner had been dismissed by Walpole for writing a protest about Government policy. He then produced the poem, praising independence of mind as a fine public virtue. [2]

Pope points out that books do not assist in reading character, while observation is misled, and our judgements are influenced by our own prejudices and tastes. Even a person’s actions may derive from something other than actual intention. He concludes that the best way to assess character is by discovering a ‘ruling passion’ (an idea previously found in An Essay on Man), [2] which may appear most significantly at a person’s death, and which ‘clue once found unravels all the rest’ (l. 178). The ideal of this is, predictably, the recipient of the poem: ‘And you! Brave COBHAM, to the latest breath Shall feel your ruling Passion strong in death:’ (ll. 262-3)

Martha Blount was one of two sisters who had been friends of Pope since 1707. Like him, she was from a Catholic background, and over the years he had visited the family frequently. His poem looks into the characters of women, in particular by describing four, supposedly pseudonymous, portraits. In three cases, however, the identity was fairly clear. Philomodé was Henrietta, Duchess of Marlborough, and Atossa was either Henrietta’s mother, Duchess Sarah, or else Catherine, Duchess of Buckingham, the illegitimate daughter of James II, while Cloe was the Countess of Suffolk, George II’s mistress.

The poem starts by apparently quoting Martha Blount: ‘Nothing so true as what you once let fall, “Most Women have no characters at all.”’ (ll. 1-2)

In fact, that view is disputed, first by reference to different portraits painted of ladies, and more importantly by varied aspects of female personality: ‘Ladies like variegated Tulips show; ‘Tis to their Changes half their charms we owe.’ (ll. 41-2) Philomedé talks of romance, but does not act it out. Atossa is angry and violent, but is eventually: ‘Sick of herself thro’ very selfishness!’ (l. 146) Cloe is the converse of this, a woman who ‘wants a Heart’, and hides in the formal social code, ‘Content to dwell in Decencies forever.’ (l. 164)

Martha herself, in contrast, is of a finer character altogether. God, he concludes, has given her ‘Sense, Good-humour, and a Poet’ (l. 292) to immortalise her.

It was not until 1744, when Pope died, that the portrait of Atossa was included in the published epistle, and it was alleged by Bolingbroke that Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, had sought to suppress it, paying Pope £1,000 [2] (perhaps £250,000 in current value).

Alexander Pope was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, Pope is best known for his satirical and discursive poetry including The Rape of the Lock, The Dunciad, and An Essay on Criticism, and for his translations of Homer.

Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke was an English politician, government official and political philosopher. He was a leader of the Tories, and supported the Church of England politically despite his antireligious views and opposition to theology. He supported the Jacobite rebellion of 1715 which sought to overthrow the new king George I. Escaping to France he became foreign minister for James Francis Edward Stuart. He was attainted for treason, but reversed course and was allowed to return to England in 1723. According to Ruth Mack, "Bolingbroke is best known for his party politics, including the ideological history he disseminated in The Craftsman (1726–1735) by adopting the formerly Whig theory of the Ancient Constitution and giving it new life as an anti-Walpole Tory principle."

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1731.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1733.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1735.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1742.

Edward Young was an English poet, best remembered for Night-Thoughts, a series of philosophical writings in blank verse, reflecting his state of mind following several bereavements. It was one of the most popular poems of the century, influencing Goethe and Edmund Burke, among many others, with its notable illustrations by William Blake.

Richard Temple, 1st Viscount Cobham was a British soldier and Whig politician. After serving as a junior officer under William III during the Williamite War in Ireland and during the Nine Years' War, he fought under John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, during the War of the Spanish Succession. During the War of the Quadruple Alliance Temple led a force of 4,000 troops on a raid on the Spanish coastline which captured Vigo and occupied it for ten days before withdrawing. In Parliament he generally supported the Whigs but fell out with Sir Robert Walpole in 1733. He was known for his ownership of and modifications to the estate at Stowe and for serving as a political mentor to the young William Pitt.

Charles Gildon, was an English hack writer and translator. He produced biographies, essays, plays, poetry, fictional letters, fables, short stories, and criticism. He is remembered best as a target of Alexander Pope in Pope's Dunciad and his Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot and as an enemy of Jonathan Swift. Due to Pope's caricature of Gildon as well as the volume and rapidity of his writings, Gildon has become the epitome of the hired pen and literary opportunist.

James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos, was an English landowner and politician who sat in the English and British House of Commons from 1698 until 1714, when he succeeded to the peerage as Baron Chandos, and vacated his seat in the House of Commons to sit in the House of Lords. He was subsequently created Earl of Carnarvon, and then Duke of Chandos in 1719.

"An Essay on Man" is a poem published by Alexander Pope in 1733–1734. It was dedicated to Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke, hence the opening line: "Awake, my St John...". It is an effort to rationalize or rather "vindicate the ways of God to man" (l.16), a variation of John Milton's claim in the opening lines of Paradise Lost, that he will "justifie the wayes of God to men" (1.26). It is concerned with the natural order God has decreed for man. Because man cannot know God's purposes, he cannot complain about his position in the great chain of being (ll.33–34) and must accept that "Whatever is, is right" (l.292), a theme that was satirized by Voltaire in Candide (1759). More than any other work, it popularized optimistic philosophy throughout England and the rest of Europe.

The Epistles of Horace were published in two books, in 20 BC and 14 BC, respectively.

The Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot is a satire in poetic form written by Alexander Pope and addressed to his friend John Arbuthnot, a physician. It was first published in 1735 and composed in 1734, when Pope learned that Arbuthnot was dying. Pope described it as a memorial of their friendship. It has been called Pope's "most directly autobiographical work", in which he defends his practice in the genre of satire and attacks those who had been his opponents and rivals throughout his career.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

Cannons was a stately home in Little Stanmore, Middlesex, England. It was built by James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos, between 1713 and 1724 at a cost of £200,000, replacing an earlier house on the site. Chandos' house was razed in 1747 and its contents dispersed.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

Martha Blount (1690–1762) was an English woman, a friend of many English literary figures, especially Alexander Pope.

Nathaniel Hooke was an English historian.

George Sewell was an English physician and poet, known as a controversialist and hack writer.