The Stikine River is a major river in northern British Columbia (BC), Canada and southeastern Alaska in the United States. It drains a large, remote upland area known as the Stikine Country east of the Coast Mountains. Flowing west and south for 610 kilometres (379 mi), it empties into various straits of the Inside Passage near Wrangell, Alaska. About 90 percent of the river's length and 95 percent of its drainage basin are in Canada. Considered one of the last truly wild large rivers in BC, the Stikine flows through a variety of landscapes including boreal forest, steep canyons and wide glacial valleys.

The Columbia Basin Project in Central Washington, United States, is the irrigation network that the Grand Coulee Dam makes possible. It is the largest water reclamation project in the United States, supplying irrigation water to over 670,000 acres (2,700 km2) of the 1,100,000 acres (4,500 km2) large project area, all of which was originally intended to be supplied and is still classified irrigable and open for the possible enlargement of the system. Water pumped from the Columbia River is carried over 331 miles (533 km) of main canals, stored in a number of reservoirs, then fed into 1,339 miles (2,155 km) of lateral irrigation canals, and out into 3,500 miles (5,600 km) of drains and wasteways. The Grand Coulee Dam, powerplant, and various other parts of the CBP are operated by the Bureau of Reclamation. There are three irrigation districts in the project area, which operate additional local facilities.

The Coquitlam River is a tributary of the Fraser River in the Canadian province of British Columbia. The river's name comes from the word Kʷikʷəƛ̓əm which translates to "Red fish up the river". The name is a reference to a sockeye salmon species that once occupied the river's waters.

Hells Gate is an abrupt narrowing of British Columbia's Fraser River, located immediately downstream of Boston Bar in the southern Fraser Canyon. The towering rock walls of the Fraser River plunge toward each other forcing the waters through a passage only 35 metres (115 ft) wide. It is also the name of the rural locality at the same location.

The Columbia River Treaty is a 1961 agreement between Canada and the United States on the development and operation of dams in the upper Columbia River basin for power and flood control benefits in both countries. Four dams were constructed under this treaty: three in the Canadian province of British Columbia and one in the U.S. state of Montana.

The Bridge River is an approximately 120 kilometres (75 mi) long river in southern British Columbia. It flows south-east from the Coast Mountains. Until 1961, it was a major tributary of the Fraser River, entering that stream about six miles upstream from the town of Lillooet; its flow, however, was near-completely diverted into Seton Lake with the completion of the Bridge River Power Project, with the water now entering the Fraser just south of Lillooet as a result.

The Stave River is a tributary of the Fraser, joining it at the boundary between the municipalities of Maple Ridge and Mission, about 35 kilometres (22 mi) east of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, in the Central Fraser Valley region.

The Nechako River arises on the Nechako Plateau east of the Kitimat Ranges of the Coast Mountains of British Columbia, Canada, and flows north toward Fort Fraser, then east to Prince George where it enters the Fraser River. "Nechako" is an anglicization of netʃa koh, its name in the indigenous Carrier language which means "big river".

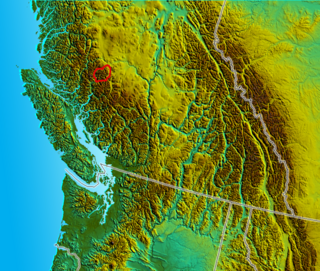

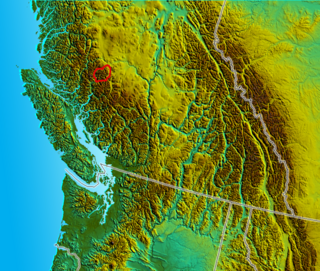

The Niut Range is 3600 km2 in area. It is a subrange of the Pacific Ranges of the Coast Mountains of British Columbia, although in some classifications it is considered part of the Chilcotin Ranges. The Niut is located in the angle of the Homathko River and its main west fork, Mosley Creek. It is isolated, island-like, by those rivers from its neighbour ranges, as both streams have their source on the Chilcotin Plateau in behind the range. Razorback Mountain is its highest peak.

The Bridge River Power Project is a hydroelectric power development in the Canadian province of British Columbia, located in the Lillooet Country between Whistler and Lillooet. It harnesses the power of the Bridge River, a tributary of the Fraser, by diverting it through a mountainside to the separate drainage basin of Seton Lake, utilizing a system of three dams, four powerhouses and a canal.

The Kenney Dam is a rock-fill embankment dam on the Nechako River in northwestern British Columbia, built in the early 1950s. The impoundment of water behind the dam forms the Nechako Reservoir, which is also commonly known as the Ootsa Lake Reservoir. The dam was constructed to power an aluminum smelter in Kitimat, British Columbia by Alcan, although in the late 1980s the company increased their economic activity by selling excess electricity across North America. The development of the dam caused various environmental problems along with the displacement of the Cheslatta T'En First Nation, whose traditional land was flooded.

The Nechako Reservoir, sometimes called the Ootsa Lake Reservoir, is a hydroelectric reservoir in British Columbia, Canada that was formed by the Kenney Dam making a diversion of the Nechako River through a 16-km intake tunnel in the Kitimat Ranges of the Coast Mountains to the 890 MW Kemano Generating Station at sea level at Kemano to service the then-new Alcan aluminum smelter at Kitimat. When it was constructed on the Nechako River in 1952, it resulted in the relocation of over 75 families. It was one of the biggest reservoirs built in Canada until the completion of the Columbia Treaty Dams and the W.A.C. Bennett Dam that created Lake Williston. The water level may swing 10 feet between 2790 and 2800 feet.

According to the International Hydropower Association, Canada is the fourth largest producer of hydroelectricity in the world in 2021 after the United States, Brazil, and China. In 2019, Canada produced 632.2 TWh of electricity with 60% of energy coming from Hydroelectric and Tidal Energy Sources).

The Iskut River, located in the northwest part of the province of British Columbia is the largest tributary of the Stikine River, entering it about 11 km (6.8 mi) above its entry into Alaska.

The Bridge River Rapids, also known as the Six Mile Rapids, the Lower Fountain, the Bridge River Fishing Grounds, and in the St'at'imcets language as Sat' or Setl, is a set of rapids on the Fraser River, located in the central Fraser Canyon at the mouth of the Bridge River six miles north of the confluence of Cayoosh Creek with the Fraser and on the northern outskirts of the District of Lillooet, British Columbia, Canada.

The Cheslatta Carrier Nation or Cheslatta T'En, of the Dakelh or Carrier people (Ta-cullies, meaning "people who go upon water" is a First Nation of the Nechako River at the headwaters of the Fraser River.

The Stung Treng Dam is a proposed hydroelectric dam on the Mekong River in Stung Treng Province, Cambodia. It would be located on the mainstream of the Lower Mekong River. The project is controversial for several reasons, including its possible impact on the fisheries, as well as other ecological and environmental factors.

The Pacific Salmon Commission is a regulatory body run jointly by the Canadian and United States governments. Its mandate is to protect stocks of the five species of Pacific salmon. Its precursor was the International Pacific Salmon Fisheries Commission, which operated from 1937 to 1985. The PSC enforces the Pacific Salmon Treaty, ratified by Canada and the U.S. in 1985.

Ruskin Dam is a concrete gravity dam on the Stave River in Ruskin, British Columbia, Canada. The dam was completed in 1930 for the primary purpose of hydroelectric power generation. The dam created Hayward Lake, which supplies water to a 105 MW powerhouse and flooded the Stave's former lower canyon, which ended in a small waterfall approximately where the dam is today.