In neuroscience, an F wave is one of several motor responses which may follow the direct motor response (M) evoked by electrical stimulation of peripheral motor or mixed nerves. F-waves are the second of two late voltage changes observed after stimulation is applied to the skin surface above the distal region of a nerve, in addition to the H-reflex which is a muscle reaction in response to electrical stimulation of innervating sensory fibers. Traversal of F-waves along the entire length of peripheral nerves between the spinal cord and muscle, allows for assessment of motor nerve conduction between distal stimulation sites in the arm and leg, and related motoneurons (MN's) in the cervical and lumbosacral cord. F-waves are able to assess both afferent and efferent loops of the alpha motor neuron in its entirety. As such, various properties of F-wave motor nerve conduction are analyzed in nerve conduction studies (NCS), and often used to assess polyneuropathies, resulting from states of neuronal demyelination and loss of peripheral axonal integrity.

A motor neuron is a neuron whose cell body is located in the motor cortex, brainstem or the spinal cord, and whose axon (fiber) projects to the spinal cord or outside of the spinal cord to directly or indirectly control effector organs, mainly muscles and glands. There are two types of motor neuron – upper motor neurons and lower motor neurons. Axons from upper motor neurons synapse onto interneurons in the spinal cord and occasionally directly onto lower motor neurons. The axons from the lower motor neurons are efferent nerve fibers that carry signals from the spinal cord to the effectors. Types of lower motor neurons are alpha motor neurons, beta motor neurons, and gamma motor neurons.

A motor nerve is a nerve that transmits motor signals from the central nervous system (CNS) to the muscles of the body. This is different from the motor neuron, which includes a cell body and branching of dendrites, while the nerve is made up of a bundle of axons. Motor nerves act as efferent nerves which carry information out from the CNS to muscles, as opposed to afferent nerves, which transfer signals from sensory receptors in the periphery to the CNS. Efferent nerves can also connect to glands or other organs/issues instead of muscles. In addition, there are nerves that serve as both sensory and motor nerves called mixed nerves.

A motor unit is made up of a motor neuron and all of the skeletal muscle fibers innervated by the neuron's axon terminals, including the neuromuscular junctions between the neuron and the fibres. Groups of motor units often work together as a motor pool to coordinate the contractions of a single muscle. The concept was proposed by Charles Scott Sherrington.

Muscle spindles are stretch receptors within the body of a skeletal muscle that primarily detect changes in the length of the muscle. They convey length information to the central nervous system via afferent nerve fibers. This information can be processed by the brain as proprioception. The responses of muscle spindles to changes in length also play an important role in regulating the contraction of muscles, for example, by activating motor neurons via the stretch reflex to resist muscle stretch.

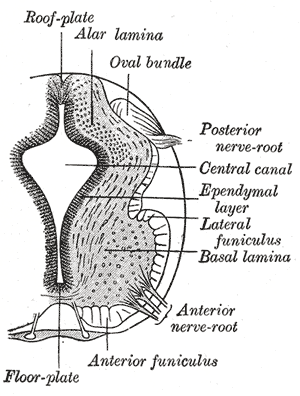

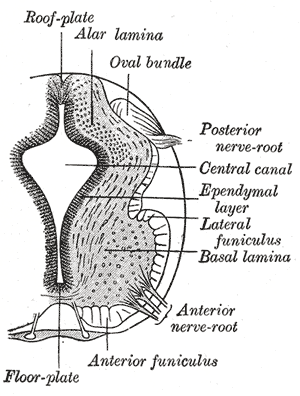

The grey column refers to a somewhat ridge-shaped mass of grey matter in the spinal cord. This presents as three columns: the anterior grey column, the posterior grey column, and the lateral grey column, all of which are visible in cross-section of the spinal cord.

A reflex arc is a neural pathway that controls a reflex. In vertebrates, most sensory neurons do not pass directly into the brain, but synapse in the spinal cord. This allows for faster reflex actions to occur by activating spinal motor neurons without the delay of routing signals through the brain. The brain will receive the input while the reflex is being carried out and the analysis of the signal takes place after the reflex action.

Lower motor neurons (LMNs) are motor neurons located in either the anterior grey column, anterior nerve roots or the cranial nerve nuclei of the brainstem and cranial nerves with motor function. Many voluntary movements rely on spinal lower motor neurons, which innervate skeletal muscle fibers and act as a link between upper motor neurons and muscles. Cranial nerve lower motor neurons also control some voluntary movements of the eyes, face and tongue, and contribute to chewing, swallowing and vocalization. Damage to the lower motor neurons can lead to flaccid paralysis, absent deep tendon reflexes and muscle atrophy.

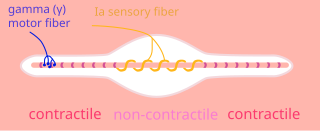

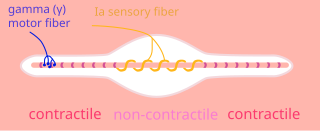

A gamma motor neuron, also called gamma motoneuron, or fusimotor neuron, is a type of lower motor neuron that takes part in the process of muscle contraction, and represents about 30% of (Aγ) fibers going to the muscle. Like alpha motor neurons, their cell bodies are located in the anterior grey column of the spinal cord. They receive input from the reticular formation of the pons in the brainstem. Their axons are smaller than those of the alpha motor neurons, with a diameter of only 5 μm. Unlike the alpha motor neurons, gamma motor neurons do not directly adjust the lengthening or shortening of muscles. However, their role is important in keeping muscle spindles taut, thereby allowing the continued firing of alpha neurons, leading to muscle contraction. These neurons also play a role in adjusting the sensitivity of muscle spindles.

Motor unit recruitment is the activation of additional motor units to accomplish an increase in contractile strength in a muscle. A motor unit consists of one motor neuron and all of the muscle fibers it stimulates. All muscles consist of a number of motor units and the fibers belonging to a motor unit are dispersed and intermingle amongst fibers of other units. The muscle fibers belonging to one motor unit can be spread throughout part, or most of the entire muscle, depending on the number of fibers and size of the muscle. When a motor neuron is activated, all of the muscle fibers innervated by the motor neuron are stimulated and contract. The activation of one motor neuron will result in a weak but distributed muscle contraction. The activation of more motor neurons will result in more muscle fibers being activated, and therefore a stronger muscle contraction. Motor unit recruitment is a measure of how many motor neurons are activated in a particular muscle, and therefore is a measure of how many muscle fibers of that muscle are activated. The higher the recruitment the stronger the muscle contraction will be. Motor units are generally recruited in order of smallest to largest as contraction increases. This is known as Henneman's size principle.

Intrafusal muscle fibers are skeletal muscle fibers that serve as specialized sensory organs (proprioceptors). They detect the amount and rate of change in length of a muscle. They constitute the muscle spindle, and are innervated by both sensory (afferent) and motor (efferent) fibers.

Motor control is the regulation of movement in organisms that possess a nervous system. Motor control includes reflexes as well as directed movement.

The stretch reflex, or more accurately "muscle stretch reflex", is a muscle contraction in response to stretching within the muscle. The reflex functions to maintain the muscle at a constant length. The term deep tendon reflex is often wrongfully used by many health workers and students to refer to this reflex. "Tendons have little to do with the response, other than being responsible for mechanically transmitting the sudden stretch from the reflex hammer to the muscle spindle. In addition, some muscles with stretch reflexes have no tendons ".

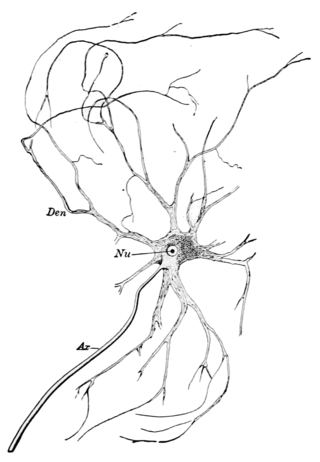

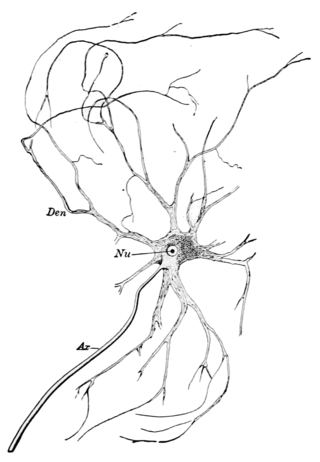

Alpha (α) motor neurons (also called alpha motoneurons), are large, multipolar lower motor neurons of the brainstem and spinal cord. They innervate extrafusal muscle fibers of skeletal muscle and are directly responsible for initiating their contraction. Alpha motor neurons are distinct from gamma motor neurons, which innervate intrafusal muscle fibers of muscle spindles.

The axon reflex is the response stimulated by peripheral nerves of the body that travels away from the nerve cell body and branches to stimulate target organs. Reflexes are single reactions that respond to a stimulus making up the building blocks of the overall signaling in the body's nervous system. Neurons are the excitable cells that process and transmit these reflex signals through their axons, dendrites, and cell bodies. Axons directly facilitate intercellular communication projecting from the neuronal cell body to other neurons, local muscle tissue, glands and arterioles. In the axon reflex, signaling starts in the middle of the axon at the stimulation site and transmits signals directly to the effector organ skipping both an integration center and a chemical synapse present in the spinal cord reflex. The impulse is limited to a single bifurcated axon, or a neuron whose axon branches into two divisions and does not cause a general response to surrounding tissue.

The Golgi tendon reflex (also called inverse stretch reflex, autogenic inhibition, tendon reflex) is an inhibitory effect on the muscle resulting from the muscle tension stimulating Golgi tendon organs (GTO) of the muscle, and hence it is self-induced. The reflex arc is a negative feedback mechanism preventing too much tension on the muscle and tendon. When the tension is extreme, the inhibition can be so great it overcomes the excitatory effects on the muscle's alpha motoneurons causing the muscle to suddenly relax. This reflex is also called the inverse myotatic reflex, because it is the inverse of the stretch reflex.

Beta motor neurons, also called beta motoneurons, are a kind of lower motor neuron, along with alpha motor neurons and gamma motor neurons. Beta motor neurons innervate intrafusal fibers of muscle spindles with collaterals to extrafusal fibers - a type of slow twitch fiber. Also, axons of alpha, beta, and gamma motor neurons become myelinated. Moreover, these efferent neurons originate from the anterior grey column of the spinal cord and travel to skeletal muscles. However, the larger diameter alpha motor fibers require higher conduction velocity than beta and gamma.

Henneman’s size principle describes relationships between properties of motor neurons and the muscle fibers they innervate and thus control, which together are called motor units. Motor neurons with large cell bodies tend to innervate fast-twitch, high-force, less fatigue-resistant muscle fibers, whereas motor neurons with small cell bodies tend to innervate slow-twitch, low-force, fatigue-resistant muscle fibers. In order to contract a particular muscle, motor neurons with small cell bodies are recruited before motor neurons with large cell bodies. It was proposed by Elwood Henneman.

Group A nerve fibers are one of the three classes of nerve fiber as generally classified by Erlanger and Gasser. The other two classes are the group B nerve fibers, and the group C nerve fibers. Group A are heavily myelinated, group B are moderately myelinated, and group C are unmyelinated.

A spinal interneuron, found in the spinal cord, relays signals between (afferent) sensory neurons, and (efferent) motor neurons. Different classes of spinal interneurons are involved in the process of sensory-motor integration. Most interneurons are found in the grey column, a region of grey matter in the spinal cord.