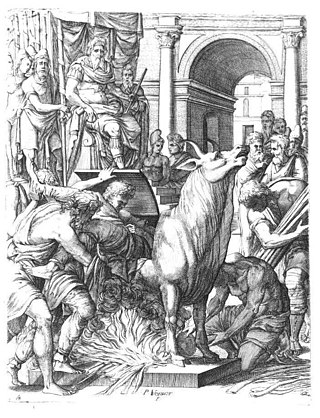

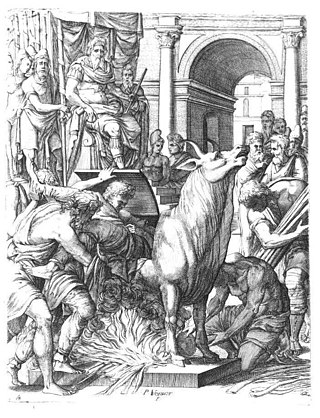

Phalaris was the tyrant of Akragas in Sicily in Magna Graecia, from approximately 570 to 554 BC.

Chariot racing was one of the most popular ancient Greek, Roman, and Byzantine sports. In Greece, chariot racing played an essential role in aristocratic funeral games from a very early time. With the institution of formal races and permanent racetracks, chariot racing was adopted by many Greek states and their religious festivals. Horses and chariots were very costly. Their ownership was a preserve of the wealthiest aristocrats, whose reputations and status benefitted from offering such extravagant, exciting displays. Their successes could be further broadcast and celebrated through commissioned odes and other poetry.

A quadriga is a car or chariot drawn by four horses abreast and favoured for chariot racing in Classical Antiquity and the Roman Empire. The word derives from the Latin quadrigae, a contraction of quadriiugae, from quadri-: four, and iugum: yoke. In Latin the word quadrigae is almost always used in the plural and usually refers to the team of four horses rather than the chariot they pull. In Greek, a four-horse chariot was known as τέθριππον téthrippon.

The Charioteer of Delphi, also known as Heniokhos, is a statue surviving from Ancient Greece, and an example of ancient bronze sculpture. The life-size (1.8m) statue of a chariot driver was found in 1896 at the Sanctuary of Apollo in Delphi. It is now in the Delphi Archaeological Museum.

The Battle of Himera, supposedly fought on the same day as the Battle of Salamis, or at the same time as the Battle of Thermopylae, saw the Greek forces of Gelon, King of Syracuse, and Theron, tyrant of Agrigentum, defeat the Carthaginian force of Hamilcar the Magonid, ending a Carthaginian bid to restore the deposed tyrant of Himera. The alleged coincidence of this battle with the naval battle of Salamis and the resultant derailing of a Punic-Persian conspiracy aimed at destroying the Greek civilization is rejected by modern scholars. Scholars also agree that the battle led to the crippling of Carthage's power in Sicily for many decades. It was one of the most important battles of the Sicilian Wars.

The sculpture of ancient Greece is the main surviving type of fine ancient Greek art as, with the exception of painted ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient Greek painting survives. Modern scholarship identifies three major stages in monumental sculpture in bronze and stone: the Archaic, Classical (480–323) and Hellenistic. At all periods there were great numbers of Greek terracotta figurines and small sculptures in metal and other materials.

Motya was an ancient and powerful city on San Pantaleo Island off the west coast of Sicily, in the Stagnone Lagoon between Drepanum and Lilybaeum. It is within the present-day commune of Marsala, Italy.

The Punic religion, Carthaginian religion, or Western Phoenician religion in the western Mediterranean was a direct continuation of the Phoenician variety of the polytheistic ancient Canaanite religion. However, significant local differences developed over the centuries following the foundation of Carthage and other Punic communities elsewhere in North Africa, southern Spain, Sardinia, western Sicily, and Malta from the ninth century BC onward. After the conquest of these regions by the Roman Republic in the third and second centuries BC, Punic religious practices continued, surviving until the fourth century AD in some cases. As with most cultures of the ancient Mediterranean, Punic religion suffused their society and there was no stark distinction between religious and secular spheres. Sources on Punic religion are poor. There are no surviving literary sources and Punic religion is primarily reconstructed from inscriptions and archaeological evidence. An important sacred space in Punic religion appears to have been the large open air sanctuaries known as tophets in modern scholarship, in which urns containing the cremated bones of infants and animals were buried. There is a long-running scholarly debate about whether child sacrifice occurred at these locations, as suggested by Greco-Roman and biblical sources.

Near the site of the first battle and great Carthaginian defeat of 480 BC, the Second Battle of Himera was fought near the city of Himera in Sicily in 409 between the Carthaginian forces under Hannibal Mago and the Ionian Greeks of Himera aided by an army and a fleet from Syracuse. Hannibal, acting under the instructions of the Carthaginian senate, had previously sacked and destroyed the city of Selinus after the Battle of Selinus in 409. Hannibal then destroyed Himera which was never rebuilt. Mass graves associated with this battle were discovered in 2008-2011, corroborating the stories told by ancient historians.

The siege of Akragas took place in 406 BCE in Sicily; the Carthaginian enterprise ultimately lasted a total of eight months. The Carthaginian army under Hannibal Mago besieged the Dorian Greek city of Akragas in retaliation for the Greek raids on Punic colonies in Sicily. The city managed to repel Carthaginian attacks until a relief army from Syracuse defeated part of the besieging Carthaginian army and lifted the siege of the city.

The Battle of Messene took place in 397 BC in Sicily. Carthage, in retaliation for the attack on Motya by Dionysius, had sent an army under Himilco, to Sicily to regain lost territory. Himilco sailed to Panormus, and from there again sailed and marched along the northern coast of Sicily to Cape Pelorum, 12 miles (19 km) north of Messene. While the Messenian army marched out to offer battle, Himilco sent 200 ships filled with soldiers to the city itself, which was stormed and the citizens were forced to disperse to forts in the countryside. Himilco later sacked and leveled the city, which was again rebuilt after the war.

Pythagoras of Samos or Pythagoras of Rhegion was an Ancient Greek sculptor from Samos. Pliny the Elder describes two different sculptors who bore a remarkable personal likeness to each other. In the nineteenth century Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, Philip Smith accepted the opinion of Karl Julius Sillig (1801–1855) that Pliny's date of Olympiad 87 ought to be referred to a Pythagoras of Samos but not a Pythagoras of Rhegium; other writers considered it possible Pythagoras of Samos lived closer to the beginning of the 5th century BC. Modern writers consider it certain these two were the same artist, and that this Pythagoras was one of the Samian exiles who moved to Zankle at the beginning of the 5th century BC and came under the power of the tyrant Anaxilas in Rhegium. While a Samian by birth, he was a pupil of Clearchus of Rhegium.

Ancient Carthage was an ancient Semitic civilisation based in North Africa. Initially a settlement in present-day Tunisia, it later became a city-state and then an empire. Founded by the Phoenicians in the ninth century BC, Carthage reached its height in the fourth century BC as one of the largest metropolises in the world. It was the centre of the Carthaginian Empire, a major power led by the Punic people who dominated the ancient western and central Mediterranean Sea. Following the Punic Wars, Carthage was destroyed by the Romans in 146 BC, who later rebuilt the city lavishly.

Himilco was a member of the Magonids, a Carthaginian family of hereditary generals, and had command over the Carthaginian forces between 406 BC and 397 BC. He is chiefly known for his war in Sicily against Dionysius I of Syracuse.

The siege and subsequent sacking of Camarina took place in 405 BC during the Sicilian Wars.

The Antonino Salinas Regional Archeological Museum is a museum in Palermo, Italy. It possesses one of the richest collections of Punic and Ancient Greek art in Italy, as well as many items related to the history of Sicily. Formerly the property of the Oratory of Saint Philip Neri, the museum is named after Antonino Salinas, a famous archaeologist and numismatist from Palermo who had served as its director from 1873 until his death in 1914, upon which he left it his major private collection. It is part of the Olivella monumental complex, which includes the Church of Sant'Ignazio all'Olivella and the adjoining Oratory.

Ancient Greek art stands out among that of other ancient cultures for its development of naturalistic but idealized depictions of the human body, in which largely nude male figures were generally the focus of innovation. The rate of stylistic development between about 750 and 300 BC was remarkable by ancient standards, and in surviving works is best seen in sculpture. There were important innovations in painting, which have to be essentially reconstructed due to the lack of original survivals of quality, other than the distinct field of painted pottery.

The Old Drunkard is a female seated statue from the Hellenistic period, which survives in two Roman marble copies. The original was probably also made of marble. This genre sculpture is notable for its stark realism.

Carthaginian or Punic currency refers to the coins of ancient Carthage, a Phoenician city-state located near present-day Tunis, Tunisia. Between the late fifth century BC and its destruction in 146 BC, Carthage produced a wide range of coinage in gold, electrum, silver, billon, and bronze. The base denomination was the shekel, probably pronounced in Punic. Only a minority of Carthaginian coinage was produced or used in North Africa. Instead, the majority derive from Carthage's holdings in Sardinia and western Sicily.

The Apobates Base is a marble statue base featuring the scene of an Apobates competition or chariot race. The base, which is part of the collection at the Acropolis Museum in Athens, stands at 42 centimetres (17 in) in height and 86 centimetres (34 in) in width. A charioteer, armed athlete or warrior, and four horse-drawn chariot are depicted in profile relief. Named for the Greek “Apobatai” – literally the “Dismounters” – the base's relief depicts the racing event or Apobates race, which was a ceremonial part of the Panathenaic Games. In this event athletes would race against other athletes by dismounting and remounting moving chariots for prizes and renown.