Related Research Articles

Progressistas is a centre-right to right-wing political party in Brazil. Founded in 1995 as the Brazilian Progressive Party, it emerged from parties that were successors to ARENA, the ruling party of the Brazilian military dictatorship. A pragmatist party, it supported the governments of presidents Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Dilma Rousseff, and Michel Temer. Largely it was the party of the politics of Paulo Maluf, a former governor and mayor of São Paulo. Of all political parties, in corruption investigation Operation Car Wash, the Progressistas had the most convictions.

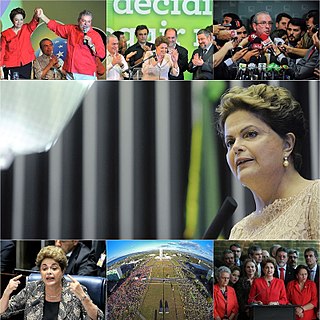

Dilma Vana Rousseff is a Brazilian economist and politician who served as the 36th president of Brazil, holding the position from 2011 until her impeachment and removal from office on 31 August 2016. She is the first woman to have held the Brazilian presidency and had previously served as chief of staff to former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva from 2005 to 2010.

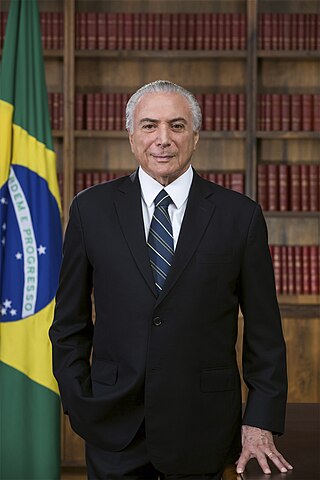

Michel Miguel Elias Temer Lulia is a Brazilian politician, lawyer and writer who served as the 37th president of Brazil from 31 August 2016 to 31 December 2018. He took office after the impeachment and removal from office of his predecessor Dilma Rousseff. He had been the 24th vice president of Brazil since 2011 and acting president since 12 May 2016, when Rousseff's powers and duties were suspended pending an impeachment trial.

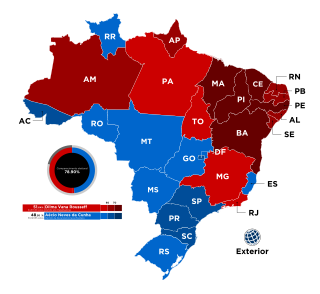

Fernando Haddad is a Brazilian academic and politician who has served as the Brazilian Minister of Finance since 1 January 2023. He was previously the Mayor of São Paulo from 2013 to 2016 and the Brazilian Minister of Education from 2005 to 2012. He was the Workers' Party candidate for President of Brazil in the 2018 election, replacing former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, whose candidacy was barred by the Superior Electoral Court under the Clean Slate law. Haddad faced Jair Bolsonaro in the run-off of the election, and lost the election with 44.87% of the votes against Bolsonaro's 55.13%.

Paulo Bernardo Silva is a Brazilian politician, member of the Workers' Party (PT). He was Minister of Communications during the government of Dilma Rousseff and Minister of Planning during the government of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

General elections were held in Brazil on 5 October 2014 to elect the president, the National Congress, and state governorships. As no candidate in the presidential election received more than 50% of the vote in the first round on 5 October 2014, a second-round runoff was held on 26 October 2014.

Corruption in Brazil exists on all levels of society from the top echelons of political power to the smallest municipalities. Operation Car Wash showed central government members using the prerogatives of their public office for rent-seeking activities, ranging from political support to siphoning funds from state-owned corporation for personal gain. Specifically, mensalão typically referred to the practice of transferring taxpayer funds as monthly allowances to members of congress from other political parties in consideration for their support and votes in congress. Politicians used the state-owned and state-run oil company Petrobras to raise hundreds of millions of reais for political campaigns and personal enrichment.

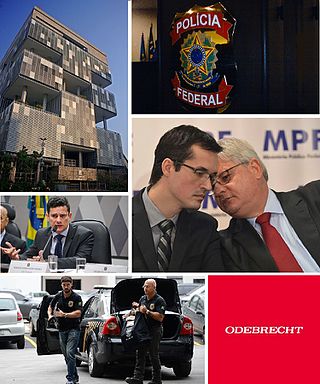

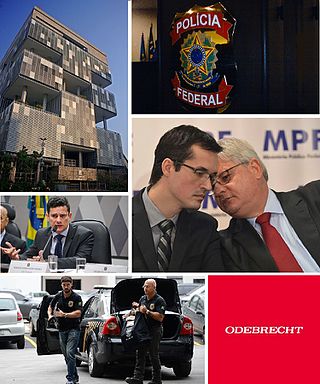

Operation Car Wash was a criminal investigation by the Federal Police of Brazil's Curitiba branch. It began in March 2014 and was initially headed by investigative judge Sérgio Moro, and in 2019 by Judge Luiz Antônio Bonat. It has resulted in more than a thousand warrants of various types. According to the Operation Car Wash task force, investigations implicate administrative members of the state-owned oil company Petrobras, politicians from Brazil's largest parties, presidents of the Chamber of Deputies and the Federal Senate, state governors, and businessmen from large Brazilian companies. The Federal Police consider it the largest corruption investigation in the country's history. The taskforce was officially disbanded on 1 February 2021.

In 2015 and 2016, a series of protests in Brazil denounced corruption and the government of President Dilma Rousseff, triggered by revelations that numerous politicians allegedly accepted bribes connected to contracts at state-owned energy company Petrobras between 2003 and 2010 and connected to the Workers' Party, while Rousseff chaired the company's board of directors. The first protests on 15 March 2015 numbered between one and nearly three million protesters against the scandal and the country's poor economic situation. In response, the government introduced anti-corruption legislation. A second day of major protesting occurred 12 April, with turnout, according to GloboNews, ranging from 696,000 to 1,500,000. On 16 August, protests took place in 200 cities in all 26 states of Brazil. Following allegations that Rousseff's predecessor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, participated in money laundering and a prosecutor ordered his arrest, record numbers of Brazilians protested against the Rousseff government on 13 March 2016, with nearly 7 million citizens demonstrating.

Eduardo Cosentino da Cunha, is a Brazilian politician and radio host, born in Rio de Janeiro. He was President of the Chamber of Deputies of Brazil from February 2015 until May 5, 2016, when he was removed from the position by the Supreme Court. BBC News labeled him the "nemesis" of Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff. He was indicted in the scandal known as Operation Car Wash involving the state-owned oil company Petrobras and other corporations. Cunha was suspended as speaker of the Chamber of Deputies by the Supreme Court on the request of the Prosecutor-General due to allegations that he had attempted to intimidate members of Congress and obstructed investigations into his alleged bribe-taking. Cunha resigned from his position later, on July 7, 2016, after a disciplinary process in Congress that had lasted nine months, making it the longest in Brazilian Congressional history. A series of legal manoeuvres had stalled the process and kept Cunha in charge of the Chamber of Deputies. While the Chamber's Commission of Ethics was divided on the issue until June, the Chamber of Deputies plenary, on September 12, 2016, voted 450–10 in favour of stripping Cunha of his position as federal deputy for breaching parliamentary decorum by lying about secret offshore bank accounts.

Free Brazil Movement is a Brazilian conservative and economically liberal movement founded in 2014. Initially a ramification of the Brazilian branch of Students for Liberty, it grew boarding the political dissatisfaction after the 2013 protests in Brazil, receiving funding from external and internal sources. Its leader is the activist and lawmaker Kim Kataguiri.

Events in the year 2016 in Brazil:

General elections were held in Brazil on 7 October 2018 to elect the president, National Congress and state governors. As no candidate in the presidential election received more than 50% of the vote in the first round, a runoff round was held on 28 October.

The impeachment of Dilma Rousseff, the 36th president of Brazil, began on 2 December 2015 with a petition for her impeachment being accepted by Eduardo Cunha, then president of the Chamber of Deputies, and continued into late 2016. Dilma Rousseff, then more than 12 months into her second four-year term, was charged with criminal administrative misconduct and disregard for the federal budget in violation of article 85, items V and VI, of the Constitution of Brazil and the Fiscal Responsibility Law, article 36. The petition also accused Rousseff of criminal responsibility for failing to act on the scandal at the Brazilian national petroleum company, Petrobras, on account of allegations uncovered by the Operation Car Wash investigation, and for failing to distance herself from the suspects in that investigation.

From mid-2014 onward, Brazil experienced a severe economic crisis. The country's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell by 3.5% in 2015 and 3.3% in 2016, after which a small economic recovery began. That recovery continued until 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic began to impact the economy again.

Joice Cristina Hasselmann is a Brazilian politician, journalist, writer, activist, and political commentator.

Janaina Conceição Paschoal is a Brazilian jurist and politician. She is a member of the Brazilian Labour Renewal Party (PRTB) since 2022, having been elected state representative of the State of São Paulo by the Social Liberal Party (PSL) from 2019 to 2023. She is also a lawyer and a law professor at the University of São Paulo.

The Odebrecht–Car Wash leniency agreement, also known in Brazil as the "end of the world plea deal", was the leniency agreement signed between Odebrecht S.A. and the Public Prosecutor's Office (PGR) in December 2016, as part of Operation Car Wash. The agreement provided for the deposition of 78 of the contractor's executives, including the former president Marcelo Odebrecht, and his father, Emílio Odebrecht, which generated 83 investigations at the Supreme Federal Court (STF).

The 2020 Brazilian protests and demonstrations were popular demonstrations that took place in several regions of Brazil, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. The protests began on March 15, 2020, with demonstrations in support of President Jair Bolsonaro, the target of several investigations, and against the isolation measures imposed by state governments.

The 2021 Brazilian protests were popular demonstrations that took place in different regions of Brazil in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Protests both supporting and opposing the government happened.

References

- ↑ Agencia Brasil (10 October 2016). "Movements launch campaign on networks in support of fighting corruption". EBC.

- ↑ "Movement Come To the Streets advocates measures to combat corruption in audience". Câmara dos Deputados.

- 1 2 "Manifesto". Vem Pra Rua. 19 March 2016.

- ↑ "Map of 10 Measures Against Corruption". Vem pra Rua. 18 November 2016.

- ↑ O Globo (18 November 2016). "Vem Pra Rua launches website to press approval of the 10 against corruption". Globo.com.

- ↑ Flavia Lima (March 19, 2016). "Vem Pra Rua Movement says now that it supports impeachment request". Valor Econômico.

- ↑ Marcos Coronato e Marco Vergotti (15 March 2015). "Manifestação anti-Dilma entra para a história". Época . Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ "Paulista reúne maior ato político desde as Diretas-Já, diz Datafolha". Folha de S.Paulo. 15 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ "Manifestantes fazem maior protesto nacional contra o governo Dilma". G1. 13 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brasil tem maior manifestação contra Dilma". UOL. 13 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ "Maior manifestação da história do País aumenta pressão por saída de Dilma". Estadão. 13 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ "A maior manifestação da história brasileira". G1. 13 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ Roney Sundays (March 16, 2016). "Protesters protest against Lula and Dilma and block Av. Paulista". G1 . Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ↑ Aguirre Talento and Machado da Costa (March 17, 2016). "Protest in Brasilia gathers 8,000 in front of Congress, says police". Folha de S.Paulo. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ↑ Elaine Patricia Cruz (March 17, 2016). "Protesters follow Avenida Paulista in protest against government". EBC . Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ↑ O Estado de São Paulo (March 19, 2016). "Pro-impeachment protesters set up tents again on Avenida Paulista". Estadão . Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Protesters roam the streets of Savassi against Dilma and Lula". State of Minas . March 20, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ↑ Martha Alves (March 20, 2016). "Pro-impeachment group continues camped on the Paulista sidewalk". Folha de S.Paulo . Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Manifestations for and against the government take place in the country this Thursday". G1. March 17, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ↑ "New injunction suspends the investiture of former President Lula da Casa Civil". Correio Braziliense. March 18, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ↑ Mario Cesar Carvalho (March 18, 2016). "Third injunction suspends Lula's tenure as minister again". Folha de S.Paulo . Retrieved March 19, 2016. }

- ↑ Mariana Oliveira (18 March 2016). "Gilmar Mendes suspends Lula's appointment as Chief of Staff". G1 . Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ↑ Karina Sgarbi (March 21, 2016). "Vem Pra Rua Movement creates online tool to monitor impeachment". Zeho Hora. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Anti-Dilma group displays in panel list of deputies against impeachment". Folha de S.Paulo. April 3, 2016. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Vem Pra Rua pressiona para que Fundo Eleitoral vá para a Saúde". April 2020.

- ↑ "Fundo para Saúde". Archived from the original on 2020-05-27. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- ↑ "To put pressure on parliamentarians, the group Vem Pra Rua creates the Impeachment Map". Free turnstile. March 22, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ↑ "Vem Pra Rua Movement launches Vergonha Wall". See SP. April. April 3, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ↑ Soares, David (2019-11-09). "Virtual map pressures Congress to approve PEC of the 2nd instance prison". Diário do Poder (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário do Poder. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ↑ Ricardo Senra (March 13, 2015). "#SalaSocial: Financing, remuneration and image: the structure of anti-Dilma groups". BBC . Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ↑ Machado da Costa, Aguirre Talento and Paula Reverbel (April 3, 2016). "Anti-government movements do not reveal origin and volume of their revenues". Folha de S.Paulo . Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ "Join us". Come Pra Rua. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- 1 2 Ricardo Chapola and Ricardo Galhardo (December 14, 2014). "The moderate, the radical and the intervener". The State of São Paulo . Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ Ricardo Senra (March 13, 2015). "#Social Room: Financing, remuneration and image: the structure of anti-Dilma groups". BBC. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- 1 2 Carla Jiménez (April 12, 2015). "Come to the Street: "Public power is deaf to the voice of the streets"". El País . Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ↑ "Movimento Vem Pra Rua summons new protest for july". Valor Econômico. June 7, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ Caroline Aleixo. "Protesters protest in support of Operation Lava Jato in Uberlândia". G1. Globo. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Vem Pra Rua demonstrates in support of Operation Lava Jato". iG. October 17, 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Bruno Bocchini (October 17, 2015). "Vem Pra Rua demonstrates in São Paulo in support of Operation Lava Jato". Agencia Brasil. EBC. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Mathias Ariel Jaimes (12 March 2016). "TV. "Lava Jato is a heritage of our country, a watershed", points out the leader of "Vem pra Rua"". TV Server. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ↑ Giovanni Sá (December 2, 2015). "PROTEST: In support of Lava Jato, Vem Pra Rua will hold demonstrations on December 12". Farol de Notícias. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ↑ Pedro Venceslau and Lisandra Paraguassu (August 13, 2015). "Protest focuses only on PT and CUT talks about 'weapons in hand'". The State of São Paulo . Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ↑ Luiz Ruffato (June 22, 2016). "The strange silence of the streets". El País . Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Come pra Rua will give president Michel Temer 'benefit of the doubt'". Gazeta do Povo. May 15, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Movements that support Dilma's impeachment request exit from Jucá". O Globo. May 23, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Jair Bolsonaro takes office as the 38th president of Brazil". VEJA (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ↑ "Ao Vivo - For 6 to 5, STF changes its understanding and takes a stand against second instance arrest". Estadão (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2020-02-23.

- ↑ Pereira, Merval. "In the UN, 193 of the 194 countries are imprisoned in the 1st or 2nd instance". Merval Pereira - O Globo (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2020-02-23.

- ↑ "OECD demands explanations from Brazil about the end of second instance prison". Economic Value (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2020-02-23.

- ↑ "Vem Pra Rua Movement calls for act in favor of second instance arrest". Congresso em Foco (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2019-10-25. Retrieved 2020-02-23.

- ↑ "Vem Pra Rua calls for a new demonstration by the 2nd instance". O Antagonista (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2019-11-26. Retrieved 2020-02-23.

- ↑ Wing Costa (May 15, 2015). "Video catches organizer of "Vem para rua" hitting the spot in the Chamber and leaving". A Gazeta . Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- 1 2 Naiara Arpini and Wing Costa (May 19, 2015). "Video shows leader of ES's 'Vem pra rua' hitting time and leaving". G1 . Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Leader of the 'Vem Pra Rua' movement is caught punching without working". O Dia . May 19, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ↑ Aliny Gamma (May 27, 2015). "Fined, lawyer threatens agents in Salvador: I have the mayor's WhatsApp". UOL . Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ↑ ""I have ACM Neto's WhatsApp": video shows disrespect for the vacancy of elderly people in Salvador". IG. May 20, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ↑ "University professor caught in a vacancy for an elderly person participates in protest against corruption". IG. May 20, 2015. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Vou ask you to be orange in something else". The Intercept. First Look Media. 2019-11-09. Retrieved 2019-11-09.