The design of experiments, also known as experiment design or experimental design, is the design of any task that aims to describe and explain the variation of information under conditions that are hypothesized to reflect the variation. The term is generally associated with experiments in which the design introduces conditions that directly affect the variation, but may also refer to the design of quasi-experiments, in which natural conditions that influence the variation are selected for observation.

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs when a particular factor is manipulated. Experiments vary greatly in goal and scale but always rely on repeatable procedure and logical analysis of the results. There also exist natural experimental studies.

Validity is the main extent to which a concept, conclusion, or measurement is well-founded and likely corresponds accurately to the real world. The word "valid" is derived from the Latin validus, meaning strong. The validity of a measurement tool is the degree to which the tool measures what it claims to measure. Validity is based on the strength of a collection of different types of evidence described in greater detail below.

Experimental psychology refers to work done by those who apply experimental methods to psychological study and the underlying processes. Experimental psychologists employ human participants and animal subjects to study a great many topics, including sensation, perception, memory, cognition, learning, motivation, emotion; developmental processes, social psychology, and the neural substrates of all of these.

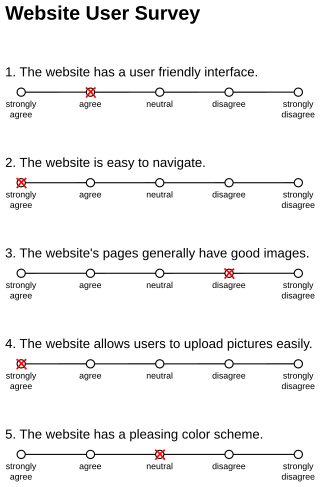

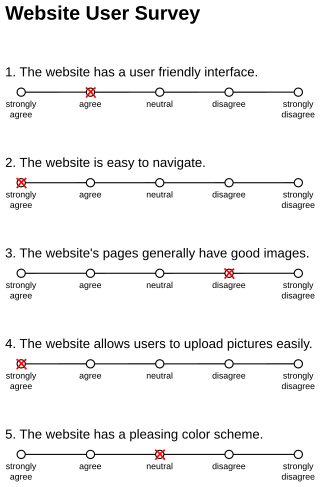

Response bias is a general term for a wide range of tendencies for participants to respond inaccurately or falsely to questions. These biases are prevalent in research involving participant self-report, such as structured interviews or surveys. Response biases can have a large impact on the validity of questionnaires or surveys.

Field experiments are experiments carried out outside of laboratory settings.

Internal validity is the extent to which a piece of evidence supports a claim about cause and effect, within the context of a particular study. It is one of the most important properties of scientific studies and is an important concept in reasoning about evidence more generally. Internal validity is determined by how well a study can rule out alternative explanations for its findings. It contrasts with external validity, the extent to which results can justify conclusions about other contexts. Both internal and external validity can be described using qualitative or quantitative forms of causal notation.

A scientific control is an experiment or observation designed to minimize the effects of variables other than the independent variable. This increases the reliability of the results, often through a comparison between control measurements and the other measurements. Scientific controls are a part of the scientific method.

External validity is the validity of applying the conclusions of a scientific study outside the context of that study. In other words, it is the extent to which the results of a study can generalize or transport to other situations, people, stimuli, and times. Generalizability refers to the applicability of a predefined sample to a broader population while transportability refers to the applicability of one sample to another target population. In contrast, internal validity is the validity of conclusions drawn within the context of a particular study.

In causal inference, a confounder is a variable that influences both the dependent variable and independent variable, causing a spurious association. Confounding is a causal concept, and as such, cannot be described in terms of correlations or associations. The existence of confounders is an important quantitative explanation why correlation does not imply causation. Some notations are explicitly designed to identify the existence, possible existence, or non-existence of confounders in causal relationships between elements of a system.

Research design refers to the overall strategy utilized to answer research questions. A research design typically outlines the theories and models underlying a project; the research question(s) of a project; a strategy for gathering data and information; and a strategy for producing answers from the data. A strong research design yields valid answers to research questions while weak designs yield unreliable, imprecise or irrelevant answers.

In social research, particularly in psychology, the term demand characteristic refers to an experimental artifact where participants form an interpretation of the experiment's purpose and subconsciously change their behavior to fit that interpretation. Typically, demand characteristics are considered an extraneous variable, exerting an effect on behavior other than that intended by the experimenter. Pioneering research was conducted on demand characteristics by Martin Orne.

In fields such as epidemiology, social sciences, psychology and statistics, an observational study draws inferences from a sample to a population where the independent variable is not under the control of the researcher because of ethical concerns or logistical constraints. One common observational study is about the possible effect of a treatment on subjects, where the assignment of subjects into a treated group versus a control group is outside the control of the investigator. This is in contrast with experiments, such as randomized controlled trials, where each subject is randomly assigned to a treated group or a control group. Observational studies, for lacking an assignment mechanism, naturally present difficulties for inferential analysis.

Single-subject research is a group of research methods that are used extensively in the experimental analysis of behavior and applied behavior analysis with both human and non-human participants. This research strategy focuses on one participant and tracks their progress in the research topic over a period of time. Single-subject research allows researchers to track changes in an individual over a large stretch of time instead of observing different people at different stages. This type of research can provide critical data in several fields, specifically psychology. It is most commonly used in experimental and applied analysis of behaviors. This research has been heavily debated over the years. Some believe that this research method is not effective at all while others praise the data that can be collected from it. Principal methods in this type of research are: A-B-A-B designs, Multi-element designs, Multiple Baseline designs, Repeated acquisition designs, Brief experimental designs and Combined designs.

A quasi-experiment is an empirical interventional study used to estimate the causal impact of an intervention on target population without random assignment. Quasi-experimental research shares similarities with the traditional experimental design or randomized controlled trial, but it specifically lacks the element of random assignment to treatment or control. Instead, quasi-experimental designs typically allow the researcher to control the assignment to the treatment condition, but using some criterion other than random assignment.

In design of experiments, single-subject curriculum or single-case research design is a research design most often used in applied fields of psychology, education, and human behaviour in which the subject serves as his/her own control, rather than using another individual/group. Researchers use single-subject design because these designs are sensitive to individual organism differences vs group designs which are sensitive to averages of groups. The logic behind single subject designs is 1) Prediction, 2) Verification, and 3) Replication. The baseline data predicts behaviour by affirming the consequent. Verification refers to demonstrating that the baseline responding would have continued had no intervention been implemented. Replication occurs when a previously observed behaviour changed is reproduced. There can be large numbers of subjects in a research study using single-subject design, however—because the subject serves as their own control, this is still a single-subject design. These designs are used primarily to evaluate the effect of a variety of interventions in applied research.

Impact evaluation assesses the changes that can be attributed to a particular intervention, such as a project, program or policy, both the intended ones, as well as ideally the unintended ones. In contrast to outcome monitoring, which examines whether targets have been achieved, impact evaluation is structured to answer the question: how would outcomes such as participants' well-being have changed if the intervention had not been undertaken? This involves counterfactual analysis, that is, "a comparison between what actually happened and what would have happened in the absence of the intervention." Impact evaluations seek to answer cause-and-effect questions. In other words, they look for the changes in outcome that are directly attributable to a program.

Psychological research refers to research that psychologists conduct for systematic study and for analysis of the experiences and behaviors of individuals or groups. Their research can have educational, occupational and clinical applications.

In the design of experiments, a between-group design is an experiment that has two or more groups of subjects each being tested by a different testing factor simultaneously. This design is usually used in place of, or in some cases in conjunction with, the within-subject design, which applies the same variations of conditions to each subject to observe the reactions. The simplest between-group design occurs with two groups; one is generally regarded as the treatment group, which receives the ‘special’ treatment, and the control group, which receives no variable treatment and is used as a reference. The between-group design is widely used in psychological, economic, and sociological experiments, as well as in several other fields in the natural or social sciences.