The Kingdom of Judah was an Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. Centered in the highlands of Judea, the kingdom's capital was Jerusalem.

Lachish was an ancient Israelite city in the Shephelah region of Canaan on the south bank of the Lakhish River mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible. The current tell by that name, known as Tel Lachish or Tell el-Duweir, has been identified with Lachish. Today, it is an Israeli national park operated and maintained by the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. It lies near the present-day moshav of Lakhish, which was named in honor of the ancient city.

Uzziah, also known as Azariah, was the tenth king of the ancient Kingdom of Judah, and one of Amaziah's sons. Uzziah was 16 when he became king of Judah and reigned for 52 years. The first 24 years of his reign were as a co-regent with his father, Amaziah.

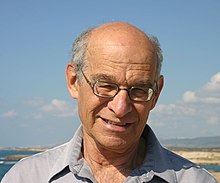

Israel Finkelstein is an Israeli archaeologist, professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University and the head of the School of Archaeology and Maritime Cultures at the University of Haifa. Finkelstein is active in the archaeology of the Levant and is an applicant of archaeological data in reconstructing biblical history. Finkelstein is the current excavator of Megiddo, a key site for the study of the Bronze and Iron Ages in the Levant.

The Amarna letters are an archive, written on clay tablets, primarily consisting of diplomatic correspondence between the Egyptian administration and its representatives in Canaan and Amurru, or neighboring kingdom leaders, during the New Kingdom, spanning a period of no more than thirty years in the middle 14th century BC. The letters were found in Upper Egypt at el-Amarna, the modern name for the ancient Egyptian capital of Akhetaten, founded by pharaoh Akhenaten during the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt.

Azekah was an ancient town in the Shephela guarding the upper reaches of the Valley of Elah, about 26 km (16 mi) northwest of Hebron.

The Jehoash Inscription is the name of a controversial artifact claimed to have been discovered in a construction site or Muslim cemetery near the Temple Mount of Jerusalem in 2001.

LMLK seals are ancient Hebrew seals stamped on the handles of large storage jars first issued in the reign of King Hezekiah and discovered mostly in and around Jerusalem. Several complete jars were found in situ buried under a destruction layer caused by Sennacherib at Lachish. While none of the original seals have been found, some 2,000 impressions made by at least 21 seal types have been published. The iconography of the two and four winged symbols are representative of royal symbols whose meaning "was tailored in each kingdom to the local religion and ideology".

Gath or Gat was one of the five cities of the Philistine pentapolis during the Iron Age. It was located in northeastern Philistia, close to the border with Judah. Gath is often mentioned in the Hebrew Bible and its existence is confirmed by Egyptian inscriptions. Already of significance during the Bronze Age, the city is believed to be mentioned in the El-Amarna letters as Gimti/Gintu, ruled by the two Shuwardata and 'Abdi-Ashtarti. Another Gath, known as Ginti-kirmil also appears in the Amarna letters.

David Ussishkin is an Israeli archaeologist and professor emeritus of archaeology.

KhirbetQeiyafa, also known as Elah Fortress and in Hebrew as Horbat Qayafa, is the site of an ancient fortress city overlooking the Elah Valley and dated to the first half of the 10th century BCE. The ruins of the fortress were uncovered in 2007, near the Israeli city of Beit Shemesh, 30 km (20 mi) from Jerusalem. It covers nearly 2.3 ha and is encircled by a 700-meter-long (2,300 ft) city wall constructed of field stones, some weighing up to eight tons. Excavations at site continued in subsequent years. A number of archaeologists, mainly the two excavators, Yosef Garfinkel and Saar Ganor, have claimed that it might be one of two biblical cities, either Sha'arayim, whose name they interpret as "Two Gates", because of the two gates discovered on the site, or Neta'im; and that the large structure at the center is an administrative building dating to the reign of King David, where he might have lodged at some point. This is based on their conclusions that the site dates to the early Iron IIA, ca. 1025–975 BCE, a range which includes the biblical date for the biblical Kingdom of David. Others suggest it might represent either a North Israelite, Philistine, or Canaanite fortress, a claim rejected by the archaeological team that excavated the site. The team's conclusion that Khirbet Qeiyafa was a fortress of King David has been criticised by some scholars. Garfinkel (2017) changed the chronology of Khirbet Qeiyafa to ca. 1000–975 BCE.

Shaaraim, possibly meaning "Two Gates", is an Israelite city mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible and the Old Testament. It has been identified by some with Khirbet Qeiyafa, an archaeological site on a hilltop overlooking the Elah Valley in the Judean hills.

Sennacherib's Annals are the annals of Sennacherib, emperor of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. They are found inscribed on several artifacts, and the final versions were found in three clay prisms inscribed with the same text: the Taylor Prism is in the British Museum, the ISAC or Chicago Prism in the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures and the Jerusalem Prism is in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

Nile silt or Nile mud is a ceramic paste employed widely within Ancient Egyptian pottery manufacture, sourced from local Quaternary Nile sediments.

The Azekah Inscription, is a tablet inscription of the reign of Sennacherib discovered in the mid-nineteenth century in the Library of Ashurbanipal. It was identified as a single tablet by Nadav Na'aman in 1974.

The Sargonid dynasty was the final ruling dynasty of Assyria, ruling as kings of Assyria during the Neo-Assyrian Empire for just over a century from the ascent of Sargon II in 722 BC to the fall of Assyria in 609 BC. Although Assyria would ultimately fall during their rule, the Sargonid dynasty ruled the country during the apex of its power and Sargon II's three immediate successors Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal are generally regarded as three of the greatest Assyrian monarchs. Though the dynasty encompasses seven Assyrian kings, two vassal kings in Babylonia and numerous princes and princesses, the term Sargonids is sometimes used solely for Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal.

Oded Lipschits is an Israeli professor in the Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near East Studies at Tel Aviv University. In 1997 he earned his Ph.D. in Jewish History under the supervision of Nadav Na'aman. He has since become a Senior Lecturer and Full Professor at Tel Aviv University and served as the Director of the Tel Aviv Institute of Archaeology since 2011. Lipschits is an incumbent of the Austria Chair of the Archeology of the Land of Israel in the Biblical Period and is the Head and founder of the Ancient Israel Studies Masters program in the Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near East Studies.

The Book of Joshua lists almost 400 ancient Levantine city names which refer to over 300 distinct locations in Israel, the West Bank, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria. Each of those cities, with minor exceptions is placed in one of the 12 regions, according to the tribes of Israel and in most cases additional details like neighbouring towns or geographical landmarks are provided. It has been serving as one of the primary sources for identifying and locating a number of Middle Bronze to Iron Age Levantine cities mentioned in ancient Egyptian and Canaanite documents, most notably in the Amarna correspondence.

Amnon Ben-Tor was an Israeli archaeologist, Professor of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He was the recipient of the 2019 Israel Prize in archaeology. His main field of expertise was the archaeology of the ancient Near East and biblical archaeology. He specialized in the art of Bronze Age carving, relationships between ancient cultures, and since 1990 focused on researching Tel Hazor as a key to solving many mysteries in the field. He was Yigal Yadin's partner in the excavations at Tel Hazor and also excavated with him at Masada, writing a book on the subject. Ben-Tor held the view that the united monarchy of Israel did indeed exist in reality as a kingdom that ruled over significant parts of the Land of Israel, contrary to the opinion of "minimalist" professors like Israel Finkelstein, Nadav Na'aman and Ze'ev Herzog, and this was based on an archaeological interpretation of findings in the field, not religious faith or ideology, as he defined it.