The internal slave trade in the United States, also known as the domestic slave trade, the Second Middle Passage and the interregional slave trade, was the mercantile trade of enslaved people within the United States. It was most significant after 1808, when the importation of slaves from Africa was prohibited by federal law. Historians estimate that upwards of one million slaves were forcibly relocated from the Upper South, places like Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Missouri, to the territories and then-new states of the Deep South, especially Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas.

Isaac Franklin was an American slave trader and plantation owner. Born to wealthy planters in what would become Sumner County, Tennessee, he assisted his brothers in trading slaves and agricultural surplus along the Mississippi River in his youth, before briefly serving in the Tennessee militia during the War of 1812. He returned to slave trading soon after the war, buying enslaved people in Virginia and Maryland, before marching them in coffles to sale at Natchez, Mississippi. He introduced John Armfield to the slave trade, and with him founded the Franklin & Armfield partnership in 1828, which would go on to become one of the largest slave trading firms in the United States. With a base of operations in Alexandria, D.C., the company shipped massive numbers of the enslaved by land and sea to markets at Natchez and New Orleans.

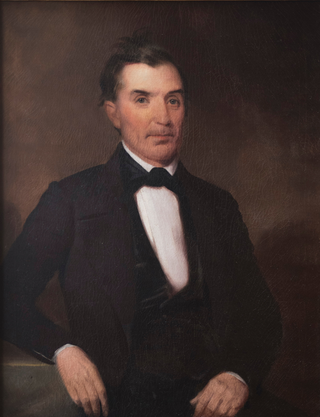

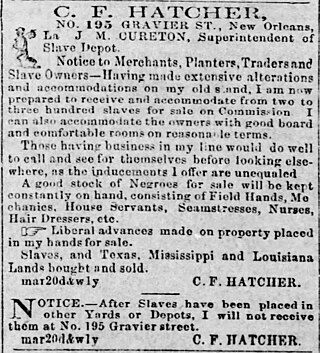

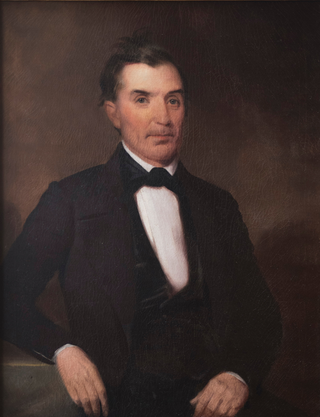

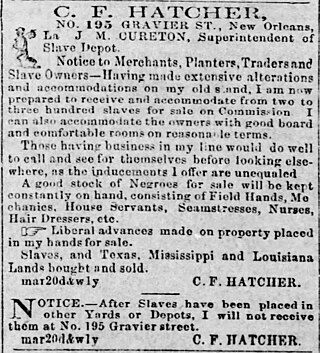

Charles F. Hatcher, typically advertising as C. F. Hatcher, was a 19th-century American slaver dealing out of Natchez, Mississippi, and New Orleans, Louisiana. He also worked as a trader of financial instruments, specie, and stocks, and as a land agent, with a special interest in selling Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas real estate to speculators and settlers.

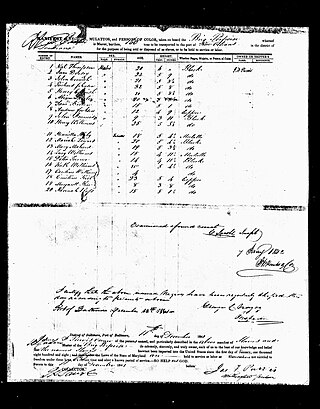

A coffle, sometimes called a platoon or a drove, was a group of enslaved people chained together and marched from one place to another by owners or slave traders. These troupes, sometimes called shipping lots before they were moved, ranged in size from a fewer than a dozen to 200 or more enslaved people.

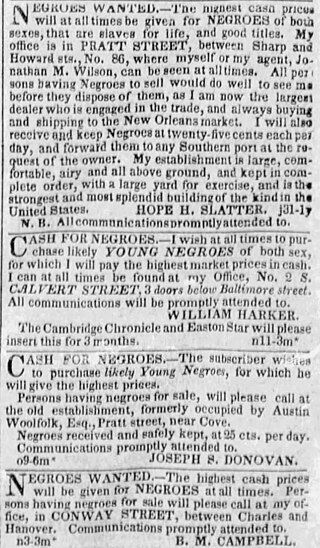

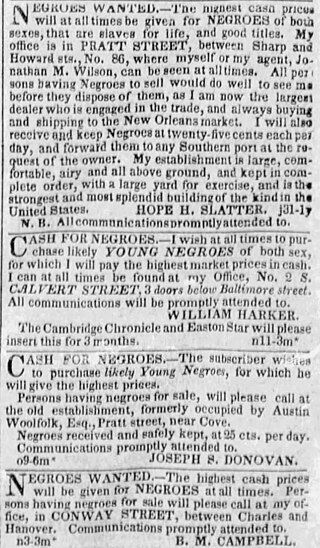

Bernard Moore Campbell and Walter L. Campbell operated an extensive slave-trading business in the antebellum U.S. South. B. M. Campbell, in company with Austin Woolfolk, Joseph S. Donovan, and Hope H. Slatter, has been described as one of the "tycoons of the slave trade" in the Upper South, "responsible for the forced departures of approximately 9,000 captives from Baltimore to New Orleans." Bernard and Walter were brothers.

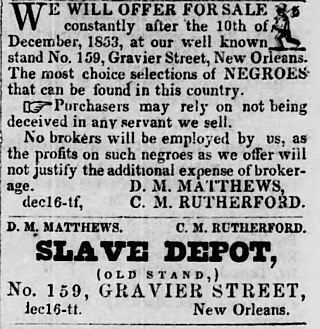

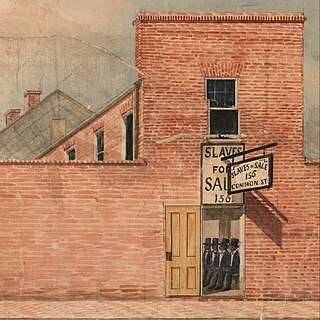

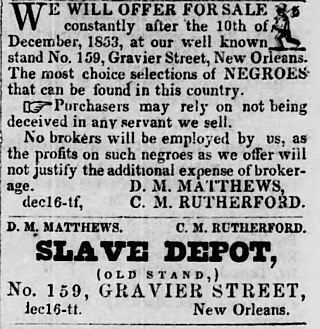

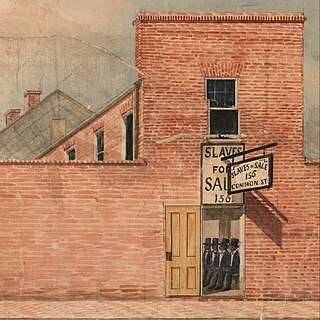

Slave markets and slave jails in the United States were places used for the slave trade in the United States from the founding in 1776 until the total abolition of slavery in 1865. Slave pens, also known as slave jails, were used to temporarily hold enslaved people until they were sold, or to hold fugitive slaves, and sometimes even to "board" slaves while traveling. Slave markets were any place where sellers and buyers gathered to make deals. Some of these buildings had dedicated slave jails, others were negro marts to showcase the slaves offered for sale, and still others were general auction or market houses where a wide variety of business was conducted, of which "negro trading" was just one part. The term slave depot was commonly used in New Orleans in the 1850s.

Theophilus Freeman was a 19th-century American slave trader of Virginia, Louisiana and Mississippi. He was known in his own time as wealthy and problematic. Freeman's business practices were described in two antebellum American slave narratives—that of John Brown and that of Solomon Northup—and he appears as a character in both filmed dramatizations of Northrup's Twelve Years a Slave.

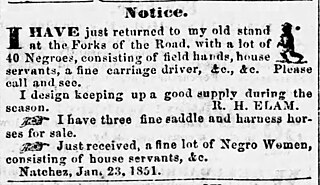

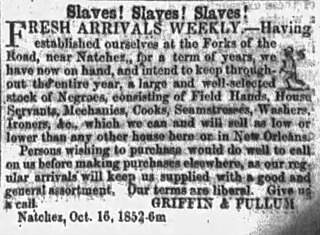

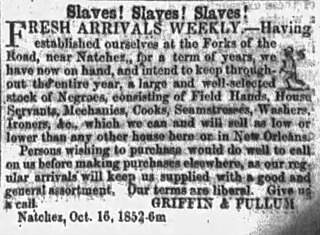

William A. Pullum was a 19th-century American slave trader, and a principal of Griffin & Pullum. He was based in Lexington, Kentucky, and for many years purchased, imprisoned, and shipped enslaved people from Virginia and Kentucky south to the Forks-of-the-Road slave market in Natchez, Mississippi.

Thomas McCargo, also styled Thos. M'Cargo, was a 19th-century American slave trader who worked in Virginia, Kentucky, Mississippi and Louisiana. He is best remembered today for being one of the slave traders aboard the Creole, which was a coastwise slave ship that was commandeered by the enslaved men aboard and sailed to freedom in the British Caribbean. The takeover of the Creole is considered the most successful slave revolt in antebellum American history.

George Kephart was a 19th-century American slave trader, land owner, farmer, and philanthropist. A native of Maryland, he was an agent of the interstate trading firm Franklin & Armfield early in his career, and later occupied, owned, and finally leased out that company's infamous slave jail in Alexandria. In 1862, Henry Wilson of Massachusetts mentioned Kephart by name in a speech on the floor of the U.S. Senate as one of the traders who had "polluted the capital of the nation with this brutalizing traffic" of selling people.

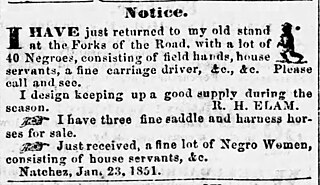

Robert H. Elam, usually advertising as R. H. Elam, was an American interstate slave trader who worked in Tennessee, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

Griffin & Pullum, later Griffin, Pullum & Co., was a 19th-century American interstate slave-trading company. The principals were Pierce Griffin and William A. Pullum. They mainly bought people in Kentucky and sold them in Mississippi.

James Franklin Purvis was an American slave trader, broker, and banker who worked primarily in Baltimore. He was a nephew of Isaac Franklin of Franklin & Armfield, and traded in Maryland, Louisiana, and Mississippi in the 1830s and early 1840s. In 1842 he became a devout Methodist, quit the slave trade, and transitioned into real estate, banking, and stock brokering. After his bank failed in 1868, he retired to Carroll County, Maryland, where he died of a heart attack in 1880 at age 72.

Calvin Morgan Rutherford, generally known as C. M. Rutherford, was a 19th-century American interstate slave trader. Rutherford had a wide geographic reach, trading nationwide from the Old Dominion of Virginia to as far west as Texas. Rutherford had ties to former Franklin & Armfield associates, worked in Kentucky for several years, advertised to markets throughout Louisiana and Mississippi, and was a major figure in the New Orleans slave trade for at least 20 years. Rutherford also invested his money in steamboats and hotels.

John T. Hatcher was a 19th-century American slave trader. He was the younger brother of slave trader C. F. Hatcher; they worked together in Natchez, Mississippi and New Orleans, Louisiana. Two days before Christmas 1858, he whipped an enslaved woman to death and fled New Orleans to avoid the consequences.

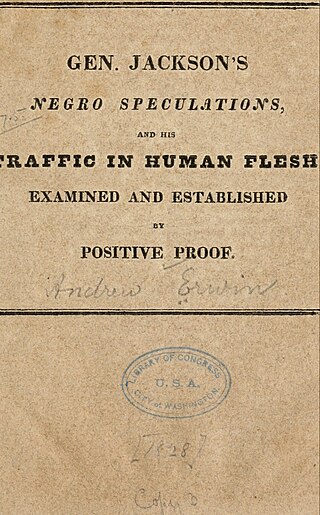

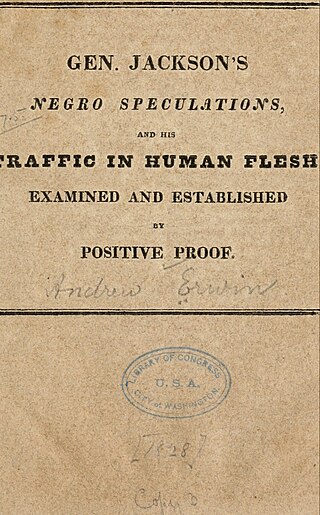

The question of whether Andrew Jackson had been a "negro trader" was a campaign issue during the 1828 United States presidential election. Jackson denied the charges, and the issue failed to connect with the electorate. Jackson was elected to be the seventh U.S. President and served for two terms, from 1829 to 1837. However, Jackson had indeed been a "speculator in slaves," participating in the interregional slave trade between Nashville, Tennessee and the Natchez and New Orleans slave markets of the lower Mississippi River valley. In addition to slaves, Jackson also dealt in real estate, horses, alcohol, and trade goods like cooking pots, knives, and fabric.

New Orleans, Louisiana was a major, if not the major, slave market of the lower Mississippi River valley of the United States from approximately 1830 until the American Civil War. Slaves from the upper south were trafficked by land and by sea to New Orleans where they were sold at a markup to the cotton and sugar plantation barons of the region.

John W. Anderson was an American interstate slave trader and farmer based near Maysville, Mason County, Kentucky. Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court John Marshall was an investor who funded Anderson's slave speculations. Anderson was involved in the establishment of the Forks of the Road slave market in 1833. Anderson was elected to the Kentucky General Assembly in 1836 but died before he could take office. A log-built slave jail established on Anderson's property is now on exhibit in the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center and is believed to be the only surviving rural American slave jail in existence.

The Richmond, Virginia slave market was the largest slave market in the Upper South region of the United States in the 1840s and 1850s. An estimated 3,000 to 9,000 slaves were sold out of Virginia annually between 1820 and 1860, many of them through Richmond. Richmond's slave traders clustered their jails and auction rooms on Wall Street, a narrow alley in a section of the city called Shockhoe Bottom, the valley created by Shockhoe Creek, which bisected the city. Traders also used the offices and meeting rooms at the Exchange Hotel, St. Charles Hotel, City Hotel and Odd Fellows' Hall. A visitor of 1852 reported, "There are four [slave depots], and all in the same street, not more than two blocks from the Exchange Hotel, where we are staying. These slave depots are in one of the most frequented streets of the place, and the sales are conducted in the building, on the first floor; and within view of the passers-by. There are small screens, behind which the men of mature years are taken for inspection; but the men and the boys are publicly examined in the open store, before an audience of full one hundred." He reported that only three of 20 men so exhibited had "clean backs" unmarked by whip scarring.