National Kitchens were restaurants established in a British Government initiative during the First World War to feed people cheaply and economically, at a time when food supplies were scarce because of the German U-boat campaign.

National Kitchens were restaurants established in a British Government initiative during the First World War to feed people cheaply and economically, at a time when food supplies were scarce because of the German U-boat campaign.

Before the outbreak of war in 1914, the United Kingdom relied on imported food to feed the population; as much as 60 percent of food stocks had come from abroad. In wartime, the increased costs of shipping together with a complete lack of any government controls led to a rapid rise in the price of food, especially meat and bread. In addition, the Imperial German Navy had launched an unrestricted submarine blockade; in April 1917, a record 550,000 tons of shipping had been sunk. [1] During the first years of the war, voluntary organisations began to open "communal kitchens" in various parts of the country. However, their public image was dreadful and only the poorest people made use of them. One government official stated: "It was thought that Public Kitchens were to be inflicted on the poor as some kind of punishment for a crime unstated". The newly created Ministry of Food adopted the idea of community kitchens but realised that they would have to be much better presented. [2]

According to historian Bryce Evans, the government was highly sensitive to possible criticism of the National Kitchens as being soup kitchens. [3] The Ministry of Food Control stated that the National Kitchens "must not resemble a soup kitchen for the poorest section of society" and should instead be places for "ordinary people in ordinary circumstances". [3] A meal of soup, meat and vegetables was available for as little as sixpence, equivalent to roughly £1 today. However, in some kitchens there was nowhere to sit [4] and in others patrons had to bring their own mugs and plates. To further distance them from charitable canteens, the kitchens were run in a businesslike manner: in at least one kitchen it was possible to "buy your Sunday dinner on Saturday"; the ability to show the means to pay for a meal in advance, and to make reservations as at a restaurant, would contribute to the image that the Kitchens were for "ordinary people." [5]

The first National Kitchen was opened by Queen Mary in Westminster Bridge Road, London, on 21 May 1917. [6] By late 1918 there were 363 National Kitchens. The kitchens were partly funded by the state and could typically feed up to 2,000 people per day. [3] They were mainly staffed by volunteers, particularly well-to-do women who were anxious to "do their bit" for the war effort; serving in the kitchens became known as "canteening". [7]

A typical menu comprised:

English cuisine encompasses the cooking styles, traditions and recipes associated with England. It has distinctive attributes of its own, but is also very similar to wider British cuisine, partly historically and partly due to the import of ingredients and ideas from the Americas, China, and India during the time of the British Empire and as a result of post-war immigration.

Pudding is a type of food which can either be a dessert served after the main meal or a savoury dish, served as part of the main meal.

A soup kitchen, food kitchen, or meal center is a place where food is offered to hungry and homeless people, usually for no cost, or sometimes at a below-market price. Frequently located in lower-income neighborhoods, soup kitchens are often staffed by volunteer organizations, such as church or community groups. Soup kitchens sometimes obtain food from a food bank for free or at a low price, because they are considered a charity, which makes it easier for them to feed the many people who require their services.

Rationing was introduced temporarily by the British government several times during the 20th century, during and immediately after a war.

Comfort food is food that provides a nostalgic or sentimental value to someone and may be characterized by its high caloric nature associated with childhood or home cooking. The nostalgia may be specific to an individual or it may apply to a specific culture.

Peasant foods are dishes eaten by peasants, made from accessible and inexpensive ingredients.

Alexis Benoît Soyer was a French chef, philanthropist, writer and inventor who made his reputation in Victorian England.

British cuisine consists of the cooking traditions and practices associated with the United Kingdom, including the regional cuisines of England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. British cuisine has its roots in the cooking traditions of the indigenous Celts, however it has been significantly influenced and shaped by subsequent waves of conquest, notably that of the Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Vikings, and the Normans; waves of migration, notably immigrants from India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Jamaica and the wider Caribbean, China, Italy, South Africa, and Eastern Europe, primarily Poland; and exposure to increasingly globalised trade and connections to the Anglosphere, particularly the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Nigerian cuisine consists of dishes or food items from the hundreds of Native African ethnic groups that comprises Nigeria. Like other West African cuisines, it uses spices and herbs with palm oil or groundnut oil to create deeply flavored sauces and soups.

Military rations, operational rations, or military provisions are goods issued to sustain the needs of military personnel. As their name suggests, military rations have historically been, and often still are, subject to rationing, with each individual receiving specific amounts from available supplies. Military-issued goods and the rationing of such goods have existed since the beginnings of organized warfare.

British Restaurants were communal kitchens created in 1940 during the Second World War to help people who had been bombed out of their homes, had run out of ration coupons or otherwise needed help. In 1943, 2,160 British Restaurants served 600,000 very inexpensive meals a day. They were disbanded in 1947. There was a political dimension as well, as the Labour Party saw them as a permanent solution to equalising consumption across the class line and guaranteeing a nourishing diet to all.

The Fray Bentos food brand is associated with tinned processed meat products, originally corned beef and later meat pies. The brand has been sold in the United Kingdom, other European countries, and Australia. Created in the second half of the 19th century, the name is derived from the port of Fray Bentos in Uruguay where the products were originally processed and packaged until the 1960s. The brand is now owned in the UK by Baxters, which manufactures the product range in Scotland. The Campbell Soup Company manufactures and sells Fray Bentos branded steak and kidney pies in Australia.

Romani cuisine is the cuisine of the ethnic Romani people. There is no specific "Roma cuisine"; it varies and is culinarily influenced by the respective countries where they have often lived for centuries. Hence, it is influenced by European cuisine even though the Romani people originated from the Indian subcontinent. Their cookery incorporates Indian and South Asian influences, but is also very similar to Hungarian cuisine. The many cultures that the Roma contacted are reflected in their cooking, resulting in many different cuisines. Some of these cultures are Middle European, Germany, Great Britain, and Spain. The cuisine of Muslim Romani people is also influenced by Balkan cuisine and Turkish cuisine. Many Roma do not eat food prepared by non-Roma.

Pea soup or split pea soup is soup made typically from dried peas, such as the split pea. It is, with variations, a part of the cuisine of many cultures. It is most often greyish-green or yellow in color depending on the regional variety of peas used; all are cultivars of Pisum sativum.

The Modern Cook was the first cookery book by the Anglo-Italian cook Charles Elmé Francatelli (1805–1876). It was first published in 1846. It was popular for half a century in the Victorian era, running through 29 London editions by 1896. It was also published in America.

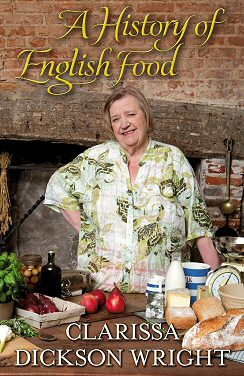

A History of English Food is a 2011 non-fiction book, a history of English cuisine arranged by period from the Middle Ages to the end of the twentieth century, written by the celebrity cook Clarissa Dickson Wright and published in London by Random House. Each period is treated in turn with a chapter. The text combines history, recipes, and anecdotes, and is illustrated with 32 pages of colour plates.

Victoria Lily Hegan Ponsonby, Baroness Sysonby, was a British cookbook author with an "eager and unconventional mind" whose recipes were popular during the 1930s and 1940s. Her friend Osbert Sitwell described her book Lady Sysonby's Cookbook as "varied, historic, traditional, and not intended for the rich man's table alone".

Kawlata is a traditional Maltese vegetable soup. It is typically made with cabbage and pork, and consumed during the winter months.

Georgina Hill was an English cookery book writer who wrote at least 21 works. She was born in Kingsdown, Bristol before moving to Tadley, Hampshire in the 1850s. She wrote her first cookery book, The Gourmet's Guide to Rabbit Cooking there in 1859. Within a year she was writing for the Routledge Household Manuals series of books, and she produced several works that specialised on an ingredient, type of food or method of cooking. Her books appear to have sold well, and were advertised in India and the US. Her 1862 work Everybody's Pudding Book was republished as A Year of Victorian Puddings in 2012.

Florence Petty was a Scottish social worker, cookery writer and broadcaster. During the 1900s, in the socially deprived area of Somers Town, north London, Petty undertook social work for the St Pancras School for Mothers, commonly known as The Mothers' and Babies' Welcome. She ran cookery demonstrations for working-class women to get them in the habit of cooking inexpensive and nutritious food. Much of the instruction was done in the women's homes, to demonstrate how to use their own limited equipment and utensils. Because she taught the women firstly how to make suet puddings—plain, sweet and meat—her students nicknamed her "The Pudding Lady". In addition to her cookery lessons, she became a qualified sanitary inspector.