In biochemistry, denaturation is a process in which proteins or nucleic acids lose the quaternary structure, tertiary structure, and secondary structure which is present in their native state, by application of some external stress or compound, such as a strong acid or base, a concentrated inorganic salt, an organic solvent, agitation and radiation, or heat. If proteins in a living cell are denatured, this results in disruption of cell activity and possibly cell death. Protein denaturation is also a consequence of cell death. Denatured proteins can exhibit a wide range of characteristics, from conformational change and loss of solubility or dissociation of cofactors to aggregation due to the exposure of hydrophobic groups. The loss of solubility as a result of denaturation is called coagulation. Denatured proteins lose their 3D structure, and therefore, cannot function.

Gel electrophoresis is a method for separation and analysis of biomacromolecules and their fragments, based on their size and charge. It is used in clinical chemistry to separate proteins by charge or size and in biochemistry and molecular biology to separate a mixed population of DNA and RNA fragments by length, to estimate the size of DNA and RNA fragments or to separate proteins by charge.

Protein biosynthesis is a core biological process, occurring inside cells, balancing the loss of cellular proteins through the production of new proteins. Proteins perform a number of critical functions as enzymes, structural proteins or hormones. Protein synthesis is a very similar process for both prokaryotes and eukaryotes but there are some distinct differences.

Structural biology, as defined by the Journal of Structural Biology, deals with structural analysis of living material at every level of organization. Early structural biologists throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries were primarily only able to study structures to the limit of the naked eye's visual acuity and through magnifying glasses and light microscopes.

Protein folding is the physical process by which a protein, after synthesis by a ribosome as a linear chain of amino acids, changes from an unstable random coil into a more ordered three-dimensional structure. This structure permits the protein to become biologically functional.

In biochemistry, globular proteins or spheroproteins are spherical ("globe-like") proteins and are one of the common protein types. Globular proteins are somewhat water-soluble, unlike the fibrous or membrane proteins. There are multiple fold classes of globular proteins, since there are many different architectures that can fold into a roughly spherical shape.

In molecular biology, the term molten globule (MG) refers to protein states that are more or less compact, but are lacking the specific tight packing of amino acid residues which creates the solid state-like tertiary structure of completely folded proteins.

In polymer chemistry, a random coil is a conformation of polymers where the monomer subunits are oriented randomly while still being bonded to adjacent units. It is not one specific shape, but a statistical distribution of shapes for all the chains in a population of macromolecules. The conformation's name is derived from the idea that, in the absence of specific, stabilizing interactions, a polymer backbone will "sample" all possible conformations randomly. Many unbranched, linear homopolymers — in solution, or above their melting temperatures — assume (approximate) random coils.

A biomolecule or biological molecule is loosely defined as a molecule produced by a living organism and essential to one or more typically biological processes. Biomolecules include large macromolecules such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic acids, as well as small molecules such as vitamins and hormones. A more general name for this class of material is biological materials. Biomolecules are an important element of living organisms, those biomolecules are often endogenous, produced within the organism but organisms usually need exogenous biomolecules, for example certain nutrients, to survive.

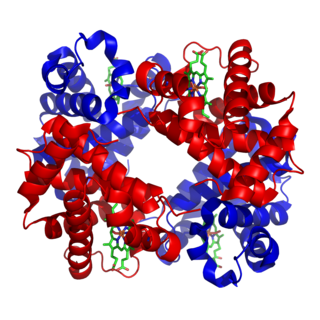

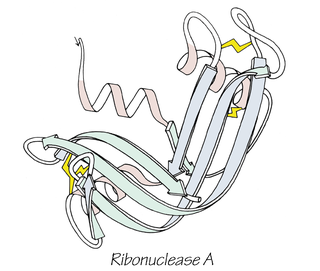

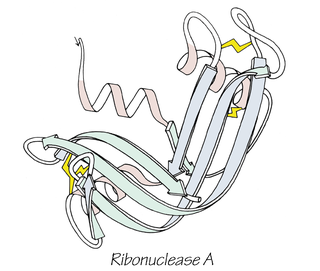

Protein structure is the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in an amino acid-chain molecule. Proteins are polymers – specifically polypeptides – formed from sequences of amino acids, which are the monomers of the polymer. A single amino acid monomer may also be called a residue, which indicates a repeating unit of a polymer. Proteins form by amino acids undergoing condensation reactions, in which the amino acids lose one water molecule per reaction in order to attach to one another with a peptide bond. By convention, a chain under 30 amino acids is often identified as a peptide, rather than a protein. To be able to perform their biological function, proteins fold into one or more specific spatial conformations driven by a number of non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, Van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic packing. To understand the functions of proteins at a molecular level, it is often necessary to determine their three-dimensional structure. This is the topic of the scientific field of structural biology, which employs techniques such as X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and dual polarisation interferometry, to determine the structure of proteins.

A chaotropic agent is a molecule in water solution that can disrupt the hydrogen bonding network between water molecules. This has an effect on the stability of the native state of other molecules in the solution, mainly macromolecules by weakening the hydrophobic effect. For example, a chaotropic agent reduces the amount of order in the structure of a protein formed by water molecules, both in the bulk and the hydration shells around hydrophobic amino acids, and may cause its denaturation.

Silent mutations are mutations in DNA that do not have an observable effect on the organism's phenotype. They are a specific type of neutral mutation. The phrase silent mutation is often used interchangeably with the phrase synonymous mutation; however, synonymous mutations are not always silent, nor vice versa. Synonymous mutations can affect transcription, splicing, mRNA transport, and translation, any of which could alter phenotype, rendering the synonymous mutation non-silent. The substrate specificity of the tRNA to the rare codon can affect the timing of translation, and in turn the co-translational folding of the protein. This is reflected in the codon usage bias that is observed in many species. Mutations that cause the altered codon to produce an amino acid with similar functionality are often classified as silent; if the properties of the amino acid are conserved, this mutation does not usually significantly affect protein function.

In molecular biology, an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) is a protein that lacks a fixed or ordered three-dimensional structure, typically in the absence of its macromolecular interaction partners, such as other proteins or RNA. IDPs range from fully unstructured to partially structured and include random coil, molten globule-like aggregates, or flexible linkers in large multi-domain proteins. They are sometimes considered as a separate class of proteins along with globular, fibrous and membrane proteins.

Biomolecular structure is the intricate folded, three-dimensional shape that is formed by a molecule of protein, DNA, or RNA, and that is important to its function. The structure of these molecules may be considered at any of several length scales ranging from the level of individual atoms to the relationships among entire protein subunits. This useful distinction among scales is often expressed as a decomposition of molecular structure into four levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary. The scaffold for this multiscale organization of the molecule arises at the secondary level, where the fundamental structural elements are the molecule's various hydrogen bonds. This leads to several recognizable domains of protein structure and nucleic acid structure, including such secondary-structure features as alpha helixes and beta sheets for proteins, and hairpin loops, bulges, and internal loops for nucleic acids. The terms primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure were introduced by Kaj Ulrik Linderstrøm-Lang in his 1951 Lane Medical Lectures at Stanford University.

The folding funnel hypothesis is a specific version of the energy landscape theory of protein folding, which assumes that a protein's native state corresponds to its free energy minimum under the solution conditions usually encountered in cells. Although energy landscapes may be "rough", with many non-native local minima in which partially folded proteins can become trapped, the folding funnel hypothesis assumes that the native state is a deep free energy minimum with steep walls, corresponding to a single well-defined tertiary structure. The term was introduced by Ken A. Dill in a 1987 article discussing the stabilities of globular proteins.

In chemical thermodynamics, conformational entropy is the entropy associated with the number of conformations of a molecule. The concept is most commonly applied to biological macromolecules such as proteins and RNA, but also be used for polysaccharides and other molecules. To calculate the conformational entropy, the possible conformations of the molecule may first be discretized into a finite number of states, usually characterized by unique combinations of certain structural parameters, each of which has been assigned an energy. In proteins, backbone dihedral angles and side chain rotamers are commonly used as parameters, and in RNA the base pairing pattern may be used. These characteristics are used to define the degrees of freedom. The conformational entropy associated with a particular structure or state, such as an alpha-helix, a folded or an unfolded protein structure, is then dependent on the probability of the occupancy of that structure.

Molecular biophysics is a rapidly evolving interdisciplinary area of research that combines concepts in physics, chemistry, engineering, mathematics and biology. It seeks to understand biomolecular systems and explain biological function in terms of molecular structure, structural organization, and dynamic behaviour at various levels of complexity. This discipline covers topics such as the measurement of molecular forces, molecular associations, allosteric interactions, Brownian motion, and cable theory. Additional areas of study can be found on Outline of Biophysics. The discipline has required development of specialized equipment and procedures capable of imaging and manipulating minute living structures, as well as novel experimental approaches.

Protein metabolism denotes the various biochemical processes responsible for the synthesis of proteins and amino acids (anabolism), and the breakdown of proteins by catabolism.

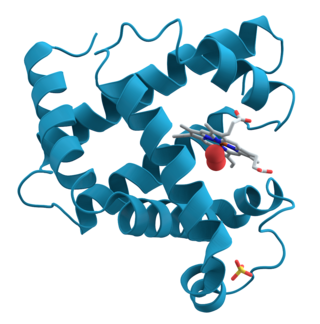

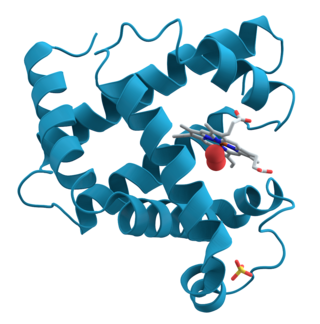

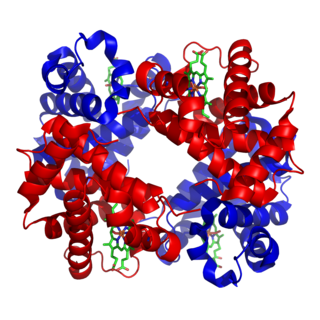

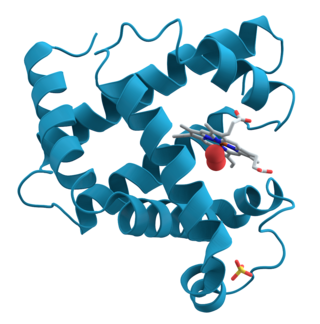

Anfinsen's dogma, also known as the thermodynamic hypothesis, is a postulate in molecular biology. It states that, at least for a small globular protein in its standard physiological environment, the native structure is determined only by the protein's amino acid sequence. The dogma was championed by the Nobel Prize Laureate Christian B. Anfinsen from his research on the folding of ribonuclease A. The postulate amounts to saying that, at the environmental conditions at which folding occurs, the native structure is a unique, stable and kinetically accessible minimum of the free energy. In other words, there are three conditions for formation of a unique protein structure:

In molecular biology, protein aggregation is a phenomenon in which intrinsically-disordered or mis-folded proteins aggregate either intra- or extracellularly. Protein aggregates have been implicated in a wide variety of diseases known as amyloidoses, including ALS, Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and prion disease.