In biochemistry, denaturation is a process in which proteins or nucleic acids lose the quaternary structure, tertiary structure, and secondary structure which is present in their native state, by application of some external stress or compound such as a strong acid or base, a concentrated inorganic salt, an organic solvent, agitation and radiation or heat. If proteins in a living cell are denatured, this results in disruption of cell activity and possibly cell death. Protein denaturation is also a consequence of cell death. Denatured proteins can exhibit a wide range of characteristics, from conformational change and loss of solubility to aggregation due to the exposure of hydrophobic groups. The loss of solubility as a result of denaturation is called coagulation. Denatured proteins lose their 3D structure and therefore cannot function.

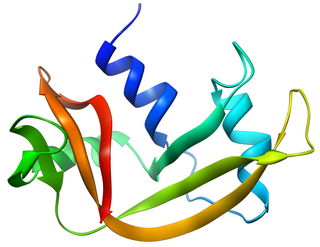

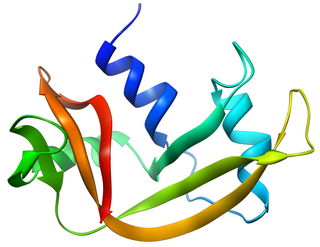

Protein tertiary structure is the three dimensional shape of a protein. The tertiary structure will have a single polypeptide chain "backbone" with one or more protein secondary structures, the protein domains. Amino acid side chains may interact and bond in a number of ways. The interactions and bonds of side chains within a particular protein determine its tertiary structure. The protein tertiary structure is defined by its atomic coordinates. These coordinates may refer either to a protein domain or to the entire tertiary structure. A number of tertiary structures may fold into a quaternary structure.

Protein folding is the physical process by which a protein chain is translated into its native three-dimensional structure, typically a "folded" conformation, by which the protein becomes biologically functional. Via an expeditious and reproducible process, a polypeptide folds into its characteristic three-dimensional structure from a random coil. Each protein exists first as an unfolded polypeptide or random coil after being translated from a sequence of mRNA into a linear chain of amino acids. At this stage, the polypeptide lacks any stable three-dimensional structure. As the polypeptide chain is being synthesized by a ribosome, the linear chain begins to fold into its three-dimensional structure.

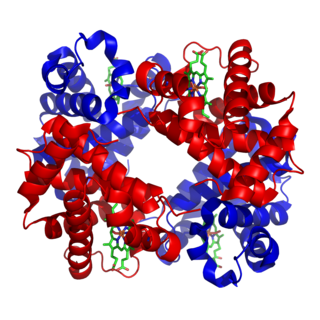

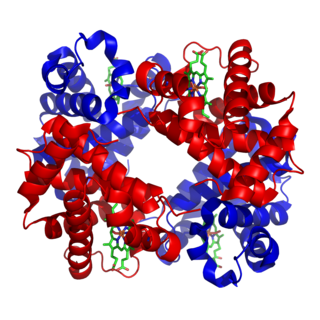

In biochemistry, globular proteins or spheroproteins are spherical ("globe-like") proteins and are one of the common protein types. Globular proteins are somewhat water-soluble, unlike the fibrous or membrane proteins. There are multiple fold classes of globular proteins, since there are many different architectures that can fold into a roughly spherical shape.

A transmembrane protein (TP) is a type of integral membrane protein that spans the entirety of the cell membrane. Many transmembrane proteins function as gateways to permit the transport of specific substances across the membrane. They frequently undergo significant conformational changes to move a substance through the membrane. They are usually highly hydrophobic and aggregate and precipitate in water. They require detergents or nonpolar solvents for extraction, although some of them (beta-barrels) can be also extracted using denaturing agents.

In biochemistry, the native state of a protein or nucleic acid is its properly folded and/or assembled form, which is operative and functional. The native state of a biomolecule may possess all four levels of biomolecular structure, with the secondary through quaternary structure being formed from weak interactions along the covalently-bonded backbone. This is in contrast to the denatured state, in which these weak interactions are disrupted, leading to the loss of these forms of structure and retaining only the biomolecule's primary structure.

In polymer chemistry, a random coil is a conformation of polymers where the monomer subunits are oriented randomly while still being bonded to adjacent units. It is not one specific shape, but a statistical distribution of shapes for all the chains in a population of macromolecules. The conformation's name is derived from the idea that, in the absence of specific, stabilizing interactions, a polymer backbone will "sample" all possible conformations randomly. Many unbranched, linear homopolymers — in solution, or above their melting temperatures — assume (approximate) random coils.

Protein structure is the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in an amino acid-chain molecule. Proteins are polymers – specifically polypeptides – formed from sequences of amino acids, the monomers of the polymer. A single amino acid monomer may also be called a residue indicating a repeating unit of a polymer. Proteins form by amino acids undergoing condensation reactions, in which the amino acids lose one water molecule per reaction in order to attach to one another with a peptide bond. By convention, a chain under 30 amino acids is often identified as a peptide, rather than a protein. To be able to perform their biological function, proteins fold into one or more specific spatial conformations driven by a number of non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, Van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic packing. To understand the functions of proteins at a molecular level, it is often necessary to determine their three-dimensional structure. This is the topic of the scientific field of structural biology, which employs techniques such as X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, cryo electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and dual polarisation interferometry to determine the structure of proteins.

The hydrophobic effect is the observed tendency of nonpolar substances to aggregate in an aqueous solution and exclude water molecules. The word hydrophobic literally means "water-fearing", and it describes the segregation of water and nonpolar substances, which maximizes hydrogen bonding between molecules of water and minimizes the area of contact between water and nonpolar molecules. In terms of thermodynamics, the hydrophobic effect is the free energy change of water surrounding a solute. A positive free energy change of the surrounding solvent indicates hydrophobicity, whereas a negative free energy change implies hydrophilicity.

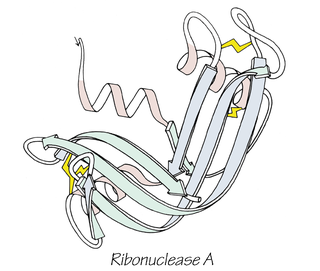

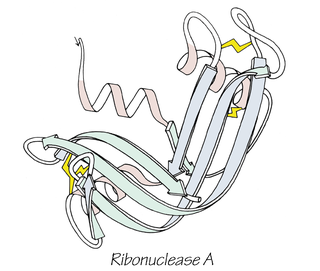

Bovine pancreatic ribonuclease, also often referred to as bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A or simply RNase A, is a pancreatic ribonuclease enzyme that cleaves single-stranded RNA. Bovine pancreatic ribonuclease is one of the classic model systems of protein science. Two Nobel Prizes in Chemistry have been awarded in recognition of work on bovine pancreatic ribonuclease: in 1972, the Prize was awarded to Christian Anfinsen for his work on protein folding and to Stanford Moore and William Stein for their work on the relationship between the protein's structure and its chemical mechanism; in 1984, the Prize was awarded to Robert Bruce Merrifield for development of chemical synthesis of proteins.

Phi value analysis, analysis, or -value analysis is an experimental protein engineering technique for studying the structure of the folding transition state of small protein domains that fold in a two-state manner. The structure of the folding transition state is hard to find using methods such as protein NMR or X-ray crystallography because folding transitions states are mobile and partly unstructured by definition. In -value analysis, the folding kinetics and conformational folding stability of the wild-type protein are compared with those of point mutants to find phi values. These measure the mutant residue's energetic contribution to the folding transition state, which reveals the degree of native structure around the mutated residue in the transition state, by accounting for the relative free energies of the unfolded state, the folded state, and the transition state for the wild-type and mutant proteins.

In biochemistry, equilibrium unfolding is the process of unfolding a protein or RNA molecule by gradually changing its environment, such as by changing the temperature or pressure, pH, adding chemical denaturants, or applying force as with an atomic force microscope tip. If the equilibrium was maintained at all steps, the process theoretically should be reversible during equilibrium folding. Equilibrium unfolding can be used to determine the thermodynamic stability of the protein or RNA structure, i.e. free energy difference between the folded and unfolded states.

The cyclol hypothesis is the now discredited first structural model of a folded, globular protein, formulated in the 1930s. It was based on the cyclol reaction of peptide bonds proposed by physicist Frederick Frank in 1936, in which two peptide groups are chemically crosslinked. These crosslinks are covalent analogs of the non-covalent hydrogen bonds between peptide groups and have been observed in rare cases, such as the ergopeptides.

The folding funnel hypothesis is a specific version of the energy landscape theory of protein folding, which assumes that a protein's native state corresponds to its free energy minimum under the solution conditions usually encountered in cells. Although energy landscapes may be "rough", with many non-native local minima in which partially folded proteins can become trapped, the folding funnel hypothesis assumes that the native state is a deep free energy minimum with steep walls, corresponding to a single well-defined tertiary structure. The term was introduced by Ken A. Dill in a 1987 article discussing the stabilities of globular proteins.

Hydrophobic collapse is a proposed process for the production of the 3-D conformation adopted by polypeptides and other molecules in polar solvents. The theory states that the nascent polypeptide forms initial secondary structure creating localized regions of predominantly hydrophobic residues. The polypeptide interacts with water, thus placing thermodynamic pressures on these regions which then aggregate or "collapse" into a tertiary conformation with a hydrophobic core. Incidentally, polar residues interact favourably with water, thus the solvent-facing surface of the peptide is usually composed of predominantly hydrophilic regions.

In chemical thermodynamics, conformational entropy is the entropy associated with the number of conformations of a molecule. The concept is most commonly applied to biological macromolecules such as proteins and RNA, but also be used for polysaccharides and other molecules. To calculate the conformational entropy, the possible conformations of the molecule may first be discretized into a finite number of states, usually characterized by unique combinations of certain structural parameters, each of which has been assigned an energy. In proteins, backbone dihedral angles and side chain rotamers are commonly used as parameters, and in RNA the base pairing pattern may be used. These characteristics are used to define the degrees of freedom. The conformational entropy associated with a particular structure or state, such as an alpha-helix, a folded or an unfolded protein structure, is then dependent on the probability of the occupancy of that structure.

Anfinsen's dogma, also known as the thermodynamic hypothesis, is a postulate in molecular biology. It states that, at least for a small globular protein in its standard physiological environment, the native structure is determined only by the protein's amino acid sequence. The dogma was championed by the Nobel Prize Laureate Christian B. Anfinsen from his research on the folding of ribonuclease A. The postulate amounts to saying that, at the environmental conditions at which folding occurs, the native structure is a unique, stable and kinetically accessible minimum of the free energy. In other words, there are three conditions for formation of a unique protein structure:

Guanidinium chloride or guanidine hydrochloride, usually abbreviated GdmCl and sometimes GdnHCl or GuHCl, is the hydrochloride salt of guanidine.

Chemical chaperones are a class of small molecules that function to enhance the folding and/or stability of proteins. Chemical chaperones are a broad and diverse group of molecules, and they can influence protein stability and polypeptide organization through a variety of mechanisms. Chemical chaperones are used for a range of applications, from production of recombinant proteins to treatment of protein misfolding in vivo.

Ahmad Salahuddin was a biochemist from India and served as a professor of biochemistry and department chairman (1984-1996) at Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) Aligarh, India. He was selected as a Founder Director of Interdisciplinary Biotechnology Unit at AMU in 1984. He was also noted by a single name as Salahuddin at AMU.

Jaremko, M., Jaremko, L., Kim, H.-Y., Cho, M.-K., Schwieters, C. D., Giller, K., Becker, S., Zweckstetter, M. (2013) Cold denaturation of a protein dimer monitored at atomic resolution, Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 264-270