The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of June 18, 1934, or the Wheeler–Howard Act, was U.S. federal legislation that dealt with the status of American Indians in the United States. It was the centerpiece of what has been often called the "Indian New Deal".

The Navajo Nation, also known as Navajoland, is a Native American reservation of Navajo people in the United States. It occupies portions of northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico, and southeastern Utah. The seat of government is located in Window Rock, Arizona.

The Long Walk of the Navajo, also called the Long Walk to Bosque Redondo, was the 1864 deportation and ethnic cleansing of the Navajo people by the United States federal government and the United States army. Navajos were forced to walk from their land in western New Mexico Territory to Bosque Redondo in eastern New Mexico. Some 53 different forced marches occurred between August 1864 and the end of 1866. Some anthropologists claim that the "collective trauma of the Long Walk...is critical to contemporary Navajos' sense of identity as a people".

Diné College is a public tribal land-grant college based in Tsaile, Arizona, serving the 27,000-square-mile (70,000 km2) Navajo Nation. It offers associate degrees, bachelor's degrees, and academic certificates.

Annie Dodge Wauneka was an influential member of the Navajo Nation as member of the Navajo Nation Council. As a member and three term head of the council's Health and Welfare Committee, she worked to improve the health and education of the Navajo. Wauneka is widely known for her countless efforts to improve health on the Navajo Nation, focusing mostly on the eradication of tuberculosis within her nation. She also authored a dictionary, in which translated English medical terms into the Navajo language. She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963 by Lyndon B. Johnson as well as the Indian Council Fire Achievement Award and the Navajo Medal of Honor. She also received an honorary doctorate in Humanities from the University of New Mexico. In 2000, Wauneka was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.

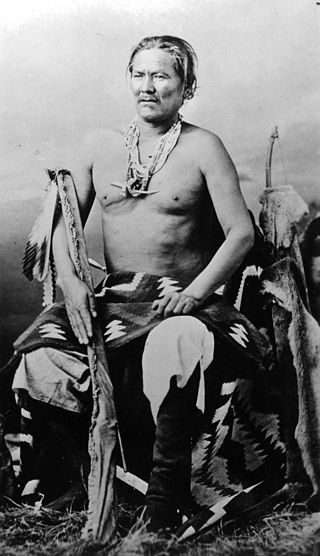

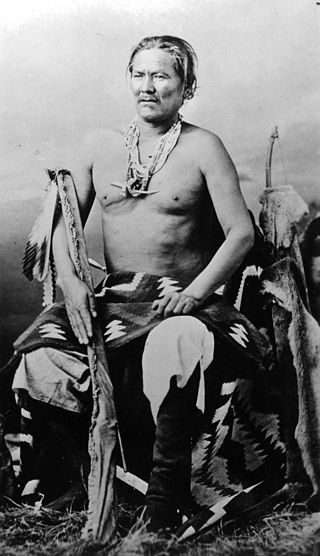

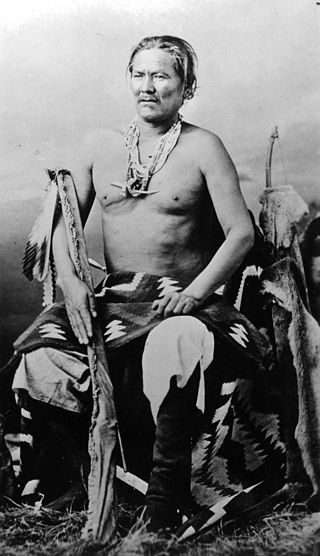

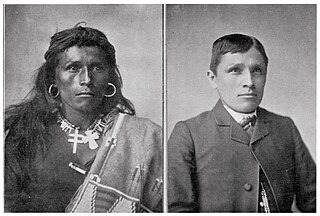

Chief Manuelito or Hastiin Chʼil Haajiní was one of the principal headmen of the Diné people before, during and after the Long Walk Period. Manuelito is the diminutive form of the name Manuel, the Iberian variant of the name Immanuel; Manuelito translates to Little Immanuel. He was born to the Bit'ahnii or ″Folded Arms People Clan″, near the Bears Ears in southeastern Utah about 1818. As many Navajo, he was known by different names depending upon context. He was Ashkii Diyinii, Dahaana Baadaané, Hastiin Ch'ilhaajinii and as Nabááh Jiłtʼaa to other Diné, and non-Navajo nicknamed him "Bullet Hole".

The Navajo-Churro, or Churro for short, is a breed of domestic sheep originating with the Spanish Churra sheep obtained by the Diné around the 16th century during the Spanish Conquest. Its wool consists of a protective topcoat and soft undercoat. Some rams have four fully developed horns, a trait shared with few other breeds in the world. The breed is highly resistant to disease. Ewes often birth twins, and they have good mothering instincts. This breed is raised primarily for wool, although some also eat their meat.

The Navajo are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

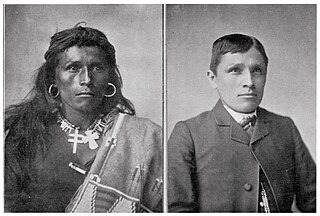

A series of efforts were made by the United States to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream European–American culture between the years of 1790 and 1920. George Washington and Henry Knox were first to propose, in the American context, the cultural assimilation of Native Americans. They formulated a policy to encourage the so-called "civilizing process". With increased waves of immigration from Europe, there was growing public support for education to encourage a standard set of cultural values and practices to be held in common by the majority of citizens. Education was viewed as the primary method in the acculturation process for minorities.

John Collier, a sociologist and writer, was an American social reformer and Native American advocate. He served as Commissioner for the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the President Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, from 1933 to 1945. He was chiefly responsible for the "Indian New Deal", especially the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, through which he intended to reverse a long-standing policy of cultural assimilation of Native Americans.

Anna Lee Walters is a Pawnee/Otoe–Missouria author.

Henry Chee Dodge, also known in Navajo by his nicknames Hastiin Adiitsʼaʼii and Kiiłchííʼ, was the last official Head Chief of the Navajo Tribe from 1884 until 1910, the first Tribal Chairman of the Navajo Business Council from 1922 until 1928, and chairman of the then Navajo Tribal Council from 1942 until 1946. He was the father of Thomas Dodge, who served as Tribal Council chairman from 1932 until 1936, and activist Annie Dodge Wauneka.

David Johns is a Navajo painter from the Seba Dalkai, Arizona, United States.

Thomas Henry Dodge (1899–1987) was a Native American lawyer and Navajo leader.

Diné College Press is the publishing division of Diné College, headquartered in Tsaile, Arizona, but whose territory spans throughout the Navajo Nation. Diné College Press has published books by and pertaining to Native Americans. While most titles focus on the issues of the Navajo people, others have dealt with broader issues pertaining to Native American studies. Authors include Acoma Pueblo poet and author Simon J. Ortiz and Pawnee-Otoe-Missouria author Anna Lee Walters.

Williams v. Lee, 358 U.S. 217 (1959), was a landmark case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the State of Arizona does not have jurisdiction to try a civil case between a non-Indian doing business on a reservation with tribal members who reside on the reservation, the proper forum for such cases being the tribal court.

The Padre Canyon incident was a skirmish in November 1899 between a group of Navajo hunters and a posse of Arizona lawmen. Among other things, it was significant in that it nearly started a large-scale Indian war in Coconino County and it led to the expansion of the Navajo Reservation. It was also the final armed conflict during a land dispute between the Navajo and American settlers, as well as one of the bloodiest.

The Treaty of Bosque Redondo also the Navajo Treaty of 1868 or Treaty of Fort Sumner, Navajo Naal Tsoos Sani or Naaltsoos Sání) was an agreement between the Navajo and the US Federal Government signed on June 1, 1868. It ended the Navajo Wars and allowed for the return of those held in internment camps at Fort Sumner following the Long Walk of 1864. The treaty effectively established the Navajo as a sovereign nation.

Charles Monty Roessel is a Navajo (Diné) photographer, journalist and academic administrator. Roessel served as Director of the Bureau of Indian Education from 2013 until 2016. He currently serves as the president of Diné College.

Sam Ahkeah was a former Navajo Nation Chairman. He was elected as the 7th chairman of the Navajo Nation Tribal Council. He served in office from 1946 through 1954 and was elected to serve for two terms. Ahkeah served as an overseer for the Mesa Verde National Park. During his time in office, Chairman Ahkeah met with the United States Congress to discuss the Colorado River Storage Project. Ahkeah advocated for the Colorado River Storage Project because it would benefit the Navajo Nation.