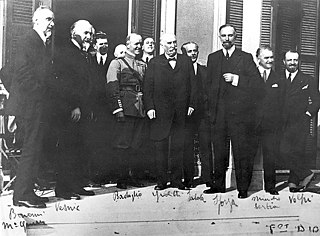

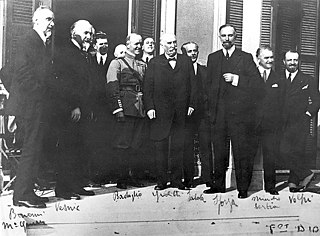

The Treaty of Rapallo was an agreement between the Kingdom of Italy and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in the aftermath of the First World War. It was intended to settle the Adriatic question, which referred to Italian claims over territories promised to the country in return for its entry into the war against Austria-Hungary, claims that were made on the basis of the 1915 Treaty of London. The wartime pact promised Italy large areas of the eastern Adriatic. The treaty, signed on 12 November 1920 in Rapallo, Italy, generally redeemed the promises of territorial gains in the former Austrian Littoral by awarding Italy territories generally corresponding to the peninsula of Istria and the former Princely County of Gorizia and Gradisca, with the addition of the Snežnik Plateau, in addition to what was promised by the London treaty. The articles regarding Dalmatia were largely ignored. Instead, in Dalmatia, Italy received the city of Zadar and several islands. Other provisions of the treaty contained safeguards for the rights of Italian nationals remaining in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, and provisions for commissions to demarcate the new border, and facilitate economic and educational cooperation. The treaty also established the Free State of Fiume, the city-state consisting of the former Austro-Hungarian Corpus separatum that consisted of Rijeka and a strip of coast giving the new state a land border with Italy at Istria.

Young Bosnia refers to a loosely organised grouping of separatist and revolutionary cells active in the early 20th century, that sought to end the Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Corfu Declaration was an agreement between the prime minister of Serbia, Nikola Pašić, and the president of the Yugoslav Committee, Ante Trumbić, concluded on the Greek island of Corfu on 20 July 1917. Its purpose was to establish the method of unifying a future common state of the South Slavs living in Serbia, Montenegro and Austria-Hungary after the First World War. Russia's decision to withdraw diplomatic support for Serbia following the February Revolution, as well as the Yugoslav Committee's sidelining by the trialist reform initiatives launched in Austria-Hungary, motivated both sides to attempt to reach an agreement.

The Yugoslav Committee was a World War I-era, unelected, ad-hoc committee. It largely consisted of émigré Croat, Slovene, and Bosnian Serb politicians and political activists whose aim was the detachment of Austro-Hungarian lands inhabited by South Slavs and unification of those lands with the Kingdom of Serbia. The group was formally established in 1915 and last met in 1919, shortly after the breakup of Austria-Hungary and the establishment of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which was later renamed Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav Committee was led by its president, the Croat lawyer Ante Trumbić, and, until 1916, by Croat politician Frano Supilo as its vice president.

Ante Trumbić was a Yugoslav and Croatian lawyer and politician in the early 20th century.

The Treaty of London or the Pact of London was a secret agreement concluded on 26 April 1915 by the United Kingdom, France, and Russia on the one part, and Italy on the other, in order to entice the latter to enter World War I on the side of the Triple Entente. The agreement involved promises of Italian territorial expansion against Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and in Africa where it was promised enlargement of its colonies. The Entente countries hoped to force the Central Powers – particularly Germany and Austria-Hungary – to divert some of their forces away from existing battlefields. The Entente also hoped that Romania and Bulgaria would be encouraged to join them after Italy did the same.

The Great People's Assembly of the Serb People in Montenegro, commonly known as the Podgorica Assembly, was an ad hoc popular assembly convened in November 1918, after the end of World War I in the Kingdom of Montenegro. The committee convened the assembly with the aim of facilitating an unconditional union of Montenegro and Serbia and removing Nikola I of Montenegro from the throne. The assembly was organised by a committee supported by and coordinating with the government of the Kingdom of Serbia. The unification was successful and preceded the establishment of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes as a unified state of South Slavs by mere days. The unification was justified by the need to establish a single Serbian state for all Serbs, including Montenegro whose population as well as Nikola I felt that Montenegro belonged to the Serbian nation and largely supported the unification.

Yugoslavia was a state concept among the South Slavic intelligentsia and later popular masses from the 19th to early 20th centuries that culminated in its realization after the 1918 collapse of Austria-Hungary at the end of World War I and the formation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. However, from as early as 1922 onward, the kingdom was better known colloquially as Yugoslavia ; in 1929 the name was made official when the country was formally renamed the "Kingdom of Yugoslavia".

The Croatian Committee was a Croatian political émigré organization, formed in the Summer of 1919, by émigré Frankist politicians and members of the former Austro-Hungarian Army. The organisation opposed the creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and aimed to achieve Croatia's independence. The Croatian Committee was established in Graz, Austria, before its headquarters were moved to Vienna and then to Budapest, Hungary. It was led by Ivo Frank.

The Temporary National Representation, also the Interim National Legislation and the Interim National Parliament, was the first legislative body established in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. It was created by the decree of Prince Regent Alexander on 24 February 1919, and convened on 1 March. Its 294 members were appointed by various provincial and regional assemblies or commissions. The main product of its work was the act regulating the election of the Constitutional Assembly. The body's work ceased after the election held on 28 November 1920.

Yugoslavism, Yugoslavdom, or Yugoslav nationalism is an ideology supporting the notion that the South Slavs, namely the Bosniaks, Bulgarians, Croats, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Serbs and Slovenes belong to a single Yugoslav nation separated by diverging historical circumstances, forms of speech, and religious divides. During the interwar period, Yugoslavism became predominant in, and then the official ideology of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. There were two major forms of Yugoslavism in the period: the regime favoured integral Yugoslavism promoting unitarism, centralisation, and unification of the country's ethnic groups into a single Yugoslav nation, by coercion if necessary. The approach was also applied to languages spoken in the Kingdom. The main alternative was federalist Yugoslavism which advocated the autonomy of the historical lands in the form of a federation and gradual unification without outside pressure. Both agreed on the concept of National Oneness developed as an expression of the strategic alliance of South Slavs in Austria-Hungary in the early 20th century. The concept was meant as a notion that the South Slavs belong to a single "race", were of "one blood", and had shared language. It was considered neutral regarding the choice of centralism or federalism.

The Green Cadres, or sometimes referred to as Green Brigades or Green Guards, were outlaw paramilitary groups that existed in Austria-Hungary from 1914 to 1918 and its successor states from 1918 to 1919. They were present in nearly all areas of Austria-Hungary, but particularly large numbers were found in Croatia-Slavonia, Bosnia, Western Slovakia, Moravia, and Galicia.

The May Declaration was a manifesto of political demands for unification of South Slav-inhabited territories within Austria-Hungary put forward to the Imperial Council in Vienna on 30 May 1917. It was authored by Anton Korošec, the leader of the Slovene People's Party. The document was signed by Korošec and thirty-two other council delegates representing South-Slavic lands within the Cisleithanian part of the dual monarchy – the Slovene Lands, the Dalmatia, Istria, and the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The delegates who signed the declaration were known as the Yugoslav Club.

The National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs claimed to represent South Slavs living in Austria-Hungary and, after its dissolution, in the short-lived State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. The council's membership was largely drawn from various representative bodies operating in the Habsburg crown lands inhabited by South Slavs. The founding of the National Council in Zagreb on 8 October 1918 fulfilled the Zagreb Resolution to concentrate South Slavic political forces, adopted earlier that year on the initiative of the Yugoslav Club. The council elected Anton Korošec as the president and Svetozar Pribićević and Ante Pavelić as vice-presidents.

In the aftermath of the First World War, the Fiume question was the dispute regarding the postwar fate of the city of Rijeka and its surroundings. An element of the Adriatic question, the dispute arose from competing claims by the Kingdom of Italy and the short-lived State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs carved out in the process of dissolution of Austria-Hungary. The latter claim was taken over by the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, itself formed through unification of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs with the Kingdom of Serbia in late 1918. In its claim, Italy relied on provisions of the Treaty of London concluded in 1915 as well as on provisions of Armistice of Villa Giusti allowing victorious Allies of World War I to occupy unspecified Austro-Hungarian territories if necessary.

The Lipošćak affair was an alleged conspiracy led by the former Austro-Hungarian Army General of the Infantry Anton Lipošćak to seize power in the recently proclaimed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs at the end of the First World War. The majority view of the allegations is that they were fabricated by allies of the Croat-Serb Coalition leader Svetozar Pribičević. Lipošćak was arrested on 22 November 1918 under suspicion of treason. He was accused of plotting to establish councils composed of workers, peasants and soldiers in place of the existing authorities with the aim of reviving the Habsburg monarchy, or working on behalf of foreign powers or the Bolsheviks.

The Geneva Declaration, Geneva Agreement, or Geneva Pact was a statement of political agreement on the provisional political system in the future union of the South Slavs living in the territories of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire and Kingdom of Serbia. It was agreed by Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić on behalf of Serbia, representatives of Serbian parliamentary opposition, representatives of the National Council of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs which recently seceded from Austria-Hungary, and representatives of the Yugoslav Committee. The talks held in Geneva, Switzerland on 6–9 November 1918 built upon and were intended to supersede the 1917 Corfu Declaration agreed by Pašić and Yugoslav Committee president Ante Trumbić. The basis for the talks was provided by the Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos on behalf of the Supreme War Council of the Triple Entente. The talks were necessary in the process of creation of Yugoslavia as a means to demonstrate to the Entente powers that various governments and interests groups could cooperate on the project to establish a viable state.

The Zagreb Resolution was a political declaration on the need for political unification of the Croats, the Slovenes and the Serbs living in Austria-Hungary. It was adopted by representatives of opposition political parties in the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia presided by Ante Pavelić in a meeting held in Zagreb on 2–3 March 1918. The declaration relied on the right of self-determination and called for establishment of an independent democratic state respecting rights of individuals and historically established polities joining the political union. It also called for ensuring cultural and religious equality in such a union. The Zagreb Resolution established a preparatory committee tasked with establishment of the National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs intended to implement the resolution. The National Council was established on 5 October in proceedings described by Pavelić as a continuation of the Zagreb conference that March.

On 5 December 1918, four days after the proclamation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, the National Guards and Sokol volunteers suppressed a protest and engaged in an armed clash against the soldiers of the 25th Regiment of the Royal Croatian Home Guard and the 53rd Regiment of the former Austro-Hungarian Common Army. National Guardsmen stopped the soldiers at the Ban Jelačić Square in Zagreb.

The Croatian state right is a legal concept in Croatian law which represents the country's rules the system of government and public administrative bodies. Croatian sources point out existence and application of those rights in the era of Croatia in personal union with Hungary and during the rule of the Habsburg monarchy, as evidence of Croatia's continuous statehood since the medieval Kingdom of Croatia. The Croatian state right is listed in the preamble of the modern Constitution of Croatia as a source of the country's sovereignty, referring to the legal status of Croatia as an independent polity within the framework of various states throughout its history.