Ethical naturalism is the meta-ethical view which claims that:

- Ethical sentences express propositions.

- Some such propositions are true.

- Those propositions are made true by objective features of the world.

- These moral features of the world are reducible to some set of non-moral features.

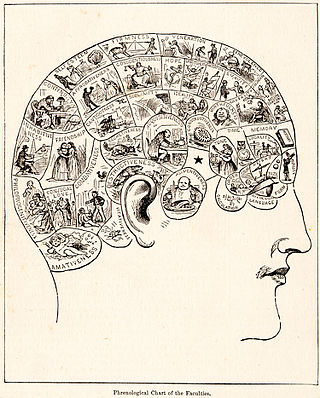

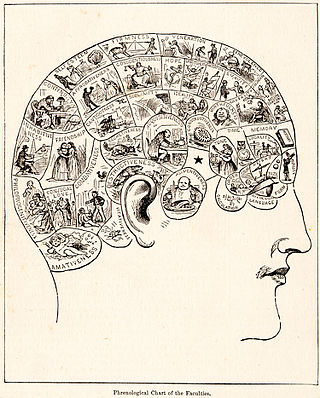

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable claims; reliance on confirmation bias rather than rigorous attempts at refutation; lack of openness to evaluation by other experts; absence of systematic practices when developing hypotheses; and continued adherence long after the pseudoscientific hypotheses have been experimentally discredited. It is not the same as junk science.

In the philosophy of science, protoscience is a research field that has the characteristics of an undeveloped science that may ultimately develop into an established science. Philosophers use protoscience to understand the history of science and distinguish protoscience from science and pseudoscience. The word roots proto- + science indicate first science.

Scientism is the belief that science and the scientific method are the best or only way to render truth about the world and reality.

Mario Augusto Bunge was an Argentine-Canadian philosopher and physicist. His philosophical writings combined scientific realism, systemism, materialism, emergentism, and other principles.

Susan Haack is a distinguished professor in the humanities, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts and Sciences, professor of philosophy, and professor of law at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Florida.

Fringe science refers to ideas whose attributes include being highly speculative or relying on premises already refuted. Fringe science theories are often advanced by people who have no traditional academic science background, or by researchers outside the mainstream discipline. The general public has difficulty distinguishing between science and its imitators, and in some cases, a "yearning to believe or a generalized suspicion of experts is a very potent incentive to accepting pseudoscientific claims".

The historiography of science or the historiography of the history of science is the study of the history and methodology of the sub-discipline of history, known as the history of science, including its disciplinary aspects and practices and the study of its own historical development.

In philosophy of science and epistemology, the demarcation problem is the question of how to distinguish between science and non-science. It also examines the boundaries between science, pseudoscience and other products of human activity, like art and literature and beliefs. The debate continues after more than two millennia of dialogue among philosophers of science and scientists in various fields. The debate has consequences for what can be termed "scientific" in topics such as education and public policy.

Massimo Pigliucci is an Italian-American philosopher and biologist who is professor of philosophy at the City College of New York, former co-host of the Rationally Speaking Podcast, and former editor in chief for the online magazine Scientia Salon. He is a critic of pseudoscience and creationism, and an advocate for secularism and science education.

Boundary-work is part of science studies. In boundary-work, boundaries, demarcations, or other divisions between fields of knowledge are created, advocated, attacked, or reinforced. Such delineations often have high stakes for the participants, and carry the implication that such boundaries are flexible and socially constructed.

Antiscience is a set of attitudes and a form of anti-intellectualism that involves a rejection of science and the scientific method. People holding antiscientific views do not accept science as an objective method that can generate universal knowledge. Antiscience commonly manifests through rejection of scientific ideas such as climate change and evolution. It also includes pseudoscience, methods that claim to be scientific but reject the scientific method. Antiscience leads to belief in false conspiracy theories and alternative medicine. Lack of trust in science has been linked to the promotion of political extremism and distrust in medical treatments.

Wissenschaft is a German-language term that embraces scholarship, research, study, higher education, and academia. Wissenschaft translates exactly into many other languages, e.g. vetenskap in Swedish or nauka in Polish, but there is no exact translation in modern English. The common translation to science can be misleading, depending on the context, because Wissenschaft equally includes humanities (Geisteswissenschaft), and sciences and humanities are mutually exclusive categories in modern English. Wissenschaft includes humanities like history, anthropology, or arts at the same level as sciences like chemistry or psychology. Wissenschaft incorporates scientific and non-scientific inquiry, learning, knowledge, scholarship, and does not necessarily imply empirical research.

The following outline is provided as a topical overview of science; the discipline of science is defined as both the systematic effort of acquiring knowledge through observation, experimentation and reasoning, and the body of knowledge thus acquired, the word "science" derives from the Latin word scientia meaning knowledge. A practitioner of science is called a "scientist". Modern science respects objective logical reasoning, and follows a set of core procedures or rules to determine the nature and underlying natural laws of all things, with a scope encompassing the entire universe. These procedures, or rules, are known as the scientific method.

A fringe theory is an idea or a viewpoint that differs significantly from the accepted scholarship of the time within its field. Fringe theories include the models and proposals of fringe science, as well as similar ideas in other areas of scholarship, such as the humanities. In a narrower sense, the term fringe theory is commonly used as a pejorative, roughly synonymous with the term pseudo-scholarship. Precise definitions that make distinctions between widely held viewpoints, fringe theories, and pseudo-scholarship are difficult to construct because of the demarcation problem. Issues of false balance or false equivalence can occur when fringe theories are presented as being equal to widely accepted theories.

The efficacy of prayer has been studied since at least 1872, generally through experiments to determine whether prayer or intercessory prayer has a measurable effect on the health of the person for whom prayer is offered. A study in 2006 indicates that intercessory prayer in cardiac bypass patients had no discernible effects.

The Science Communication Observatory is a Special Research Centre attached to the Department of Communication of the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, set up in 1994. This centre is specialized in the study and analysis of the transmission of scientific, medical, environmental and technological knowledge to society. The journalist Vladimir de Semir, associated professor of Science Journalism at the Pompeu Fabra University, was the founder and is the current director of the centre. A multidisciplinary team of researchers coming from different backgrounds is working on various lines of research: science communication; popularization of sciences, risk and crisis communication; science communication and knowledge representation; journalism specialized in science and technology; scientific discourse analysis; health and medicine in the daily press; relationships between science journals and mass media; history of science communication; public understanding of science; gender and science in the mass media, promotion of scientific vocations, science museology, etc.

Thomas F. Gieryn is Rudy Professor of Sociology at Indiana University. He is also the Vice Provost of Faculty and Academic Affairs. In his research, he focuses on philosophy and sociology of science from a cultural, social, historical, and humanistic perspective. He is known for developing the concept of "boundary-work," that is, instances in which boundaries, demarcations, or other divisions between fields of knowledge are created, advocated, attacked, or reinforced. He has served on many councils and boards, including the Advisory Board of the exhibition on "Science in American Life" by the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History. He retired in 2015 from his professorship at Indiana University.

Non-overlapping magisteria (NOMA) is the view, advocated by paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, that science and religion each represent different areas of inquiry, fact vs. values, so there is a difference between the "nets" over which they have "a legitimate magisterium, or domain of teaching authority", and the two domains do not overlap. He suggests, with examples, that "NOMA enjoys strong and fully explicit support, even from the primary cultural stereotypes of hard-line traditionalism" and that it is "a sound position of general consensus, established by long struggle among people of goodwill in both magisteria." Some have criticized the idea or suggested limitations to it, and there continues to be disagreement over where the boundaries between the two magisteria should be.

Astrology consists of a number of belief systems that hold that there is a relationship between astronomical phenomena and events or descriptions of personality in the human world. Astrology has been rejected by the scientific community as having no explanatory power for describing the universe. Scientific testing has found no evidence to support the premises or purported effects outlined in astrological traditions.