Nazi plunder was the stealing of art and other items which occurred as a result of the organized looting of European countries during the time of the Nazi Party in Germany.

The Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program (MFAA) under the Civil Affairs and Military Government Sections of the Allied armies was established in 1943 to help protect cultural property in war areas during and after World War II. The group of approximately 400 service members and civilians worked with military forces to safeguard historic and cultural monuments from war damage, and as the conflict came to a close, to find and return works of art and other items of cultural importance that had been stolen by the Nazis or hidden for safekeeping. Some of them are portrayed and honored in the 2014 film The Monuments Men.

Wilhelm Peter Bruno Lohse was a German art dealer and SS-Hauptsturmführer who, during World War II, became the chief art looter in Paris for Hermann Göring, helping the Nazi leader amass a vast collection of plundered artworks. During the war, Göring boasted that he owned the largest private art collection in Europe.

The Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz (KHI) is one of the oldest research institutions dedicated to the history of art and architecture in Italy, where facets of European, Mediterranean and global history are investigated.

Kunstschutz is the German term for the principle of preserving cultural heritage and artworks during armed conflict, especially during the first and second world wars, with the stated aim of protecting the enemy's art and returning after the end of hostilities. It is associated with the image of the "art officer" (Kunstoffizier) or "art expert" (Kunstsachverständiger).

The Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce was a Nazi Party organization dedicated to appropriating cultural property during the Second World War. It was led by the chief ideologue of the Nazi Party, Alfred Rosenberg, from within the NSDAP Office of Foreign Affairs. Between 1940 and 1945, the ERR operated in France, Netherlands, Belgium, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Greece, Italy, and on the territory of the Soviet Union in the Reichskommissariat Ostland and Reichskommissariat Ukraine. Much of the looted material was recovered by the Allies after the war, and returned to rightful owners, but there remains a substantial part that has been lost or remains with the Allied powers.

The Munich Central Collecting Point was a depot used by the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program after the end of the Second World War to process, photograph and redistribute artwork and cultural artifacts that had been confiscated by the Nazis and hidden throughout Germany and Austria. Other Central Collecting Points were located at Marburg, Wiesbaden and Offenbach, with the overall aim of giving restitution for the artifacts to their countries of origin.

Seymour Pomrenze was a Jewish-American archivist and records manager. He was the first director of the Offenbach Archival Depot, the primary Allied collection point for books and archival material looted by the Nazis.

Leslie Irlyn Poste (1918–1996) was a librarian in the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program at the end of World War II, and was active in the preservation, conservation and restitution of books, scrolls, manuscripts and reports accumulated by the German government from the occupied countries.

Isaac Bencowitz (1896–1972) was a captain in the US Army's Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program after World War II.

Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Inc. was an organization established by the Conference on Jewish Relations in April 1947 to collect and distribute heirless Jewish property in the American occupied zone of Germany after World War II. The organization, originally named the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, was originally proposed in 1944 by Theodor Gaster of the Library of Congress, and one of its cofounders.

Alois Miedl was a naturalized Dutch art dealer, originally a German Nazi banker, born in Munich, who had moved to and was mainly active in the Netherlands, involved with the sales of properties stolen from Jews who had fled or had been deported.

Josef "Sepp" Angerer (1899–1961) was a rug merchant and art dealer who acted as an agent for Hermann Göring's private art collection, immediately before and during the Second World War. Art that Angerer dealt with for Göring came from a variety of sources: looted, acquired using threats, bought on the open market, and appropriated from museums.

Theodor Fischer (1878–1957) was a Swiss art dealer and auctioneer in Lucerne who after the First World War built a highly successful firm of auctioneers that dominated the Swiss art market. In 1939 he was the auctioneer at the infamous Grand Hotel auction of "degenerate art" removed from German museums by the Nazis. During the Second World War he played a key part in the trading of art looted by the Germans from occupied countries.

Moïse Lévy de Benzion (1873–1943) was an Egyptian department store owner who built an important collection of art and antiquities. The collection was plundered by the Nazis in France during the Second World War and nearly 1000 items seized.

The German Nazi Party protected art, gold and other objects that had been either plundered or moved for safekeeping at various storage sites during World War II. These sites included salt mines at Altaussee and Merkers and a copper mine at Siegen.

Kurt Freiherr von Behr headed the Nazi art looting organisation, Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), in Paris and was involved in the M-Action which looted the home furnishings of French Jews.

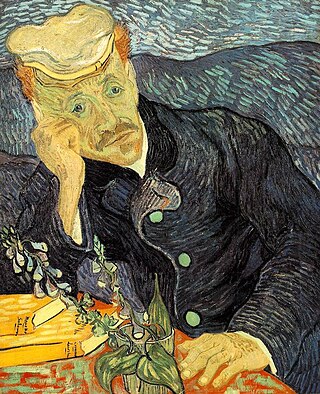

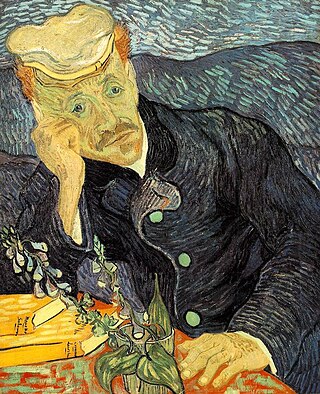

Many priceless artworks by the Dutch post-impressionist artist Vincent van Gogh were looted by Nazis during 1933–1945, mostly from Jewish collectors forced into exile or murdered.

The Hermann Göring Collection, also known as the Kunstsammlung Hermann Göring, was an extensive private art collection of Nazi Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, formed for the most part by looting of Jewish property in Nazi-occupied areas between 1936 and 1945.