Opium is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy Papaver somniferum. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which is processed chemically to produce heroin and other synthetic opioids for medicinal use and for the illegal drug trade. The latex also contains the closely related opiates codeine and thebaine, and non-analgesic alkaloids such as papaverine and noscapine. The traditional, labor-intensive method of obtaining the latex is to scratch ("score") the immature seed pods (fruits) by hand; the latex leaks out and dries to a sticky yellowish residue that is later scraped off and dehydrated. The word meconium historically referred to related, weaker preparations made from other parts of the opium poppy or different species of poppies.

The illegal drug trade, drug trafficking, or narcotrafficking is a global black market dedicated to the cultivation, manufacture, distribution and sale of prohibited drugs. Most jurisdictions prohibit trade, except under license, of many types of drugs through the use of drug prohibition laws. The think tank Global Financial Integrity's Transnational Crime and the Developing World report estimates the size of the global illicit drug market between US$426 and US$652 billion in 2014 alone. With a world GDP of US$78 trillion in the same year, the illegal drug trade may be estimated as nearly 1% of total global trade. Consumption of illegal drugs is widespread globally, and it remains very difficult for local authorities to reduce the rates of drug consumption.

Nadia Anjuman was a poet from Afghanistan.

Malalai Joya is an activist, writer, and a politician from Afghanistan. She served as a Parliamentarian in the National Assembly of Afghanistan from 2005 until early 2007, after being dismissed for publicly denouncing the presence of warlords and war criminals in the Afghan Parliament. She was an outspoken critic of the Karzai administration and its western supporters, particularly the United States.

Afghanistan has long had a history of opium poppy cultivation and harvest. As of 2021, Afghanistan's harvest produces more than 90% of illicit heroin globally, and more than 95% of the European supply. More land is used for opium in Afghanistan than is used for coca cultivation in Latin America. The country has been the world's leading illicit drug producer since 2001. In 2007, 93% of the non-pharmaceutical-grade opiates on the world market originated in Afghanistan. By 2019 Afghanistan still produced about 84% of the world market. This amounts to an export value of about US $4 billion, with a quarter being earned by opium farmers and the rest going to district officials, insurgents, warlords, and drug traffickers. In the seven years (1994–2000) prior to a Taliban opium ban, the Afghan farmers' share of gross income from opium was divided among 200,000 families.

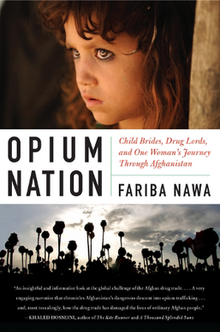

Fariba Nawa is an Afghan-American freelance journalist who grew up in both Herat and Lashkargah in Afghanistan as well as Fremont, California. She was born in Herat, Afghanistan to a native Afghan family. Her family fled the country during the Soviet invasion in the 1980s. She is trilingual in Persian, Arabic, and English. She has done her master's degree in Middle Eastern Studies and Journalism from New York University. In 2000 she ventured into Taliban controlled Afghanistan by sneaking into the country through Iran. She lived and reported from Afghanistan from 2000 to 2007. Furthermore, She travelled extensively in Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, Egypt, and Germany, reporting on her experiences.

Nāwa-I-Barakzāyi District or Trek Nawa is an administrative district in Helmand Province, Afghanistan located south of the provincial capital of Lashkar Gah along the Helmand River. It is bordered by the districts of Lashkar Gah, Nad Ali, Garmsir, and Rig, as well as the provinces of Nimruz and Kandahar. It falls within the area known as Pashtunistan,, an area comprising most of southeast Afghanistan and northwest Pakistan. The dominant language is Pashto and many of the 89,000 residents practice the traditional code of Pashtunwali. Nawa-I-Barakzayi's name reflects the dominant Pashtun tribe in the district, the Barakzai. Prior to the 1970s, it was called Shamalan after a small village at the south end of the district

The Ghurian District is an Afghan administrative district (Wuleswali) in far western Afghanistan in western Herat Province. The district is bordered by Iran to the west and northwest. It is then bordered by other districts of Herat, Kohsan District in the north, Zendeh Jan District to the east, and Adraskan District to the south. The Hari River flows through the northeastern end of the district. The border with Iran is marshy. The population is 85,900 and the district center is the city of Ghurian.

A Thousand Splendid Suns is a 2007 novel by Afghan-American author Khaled Hosseini, following the huge success of his bestselling 2003 debut The Kite Runner. Mariam, an illegitimate teenager from Herat, is forced to marry a shoemaker from Kabul after a family tragedy. Laila, born a generation later, lives a relatively privileged life, but her life intersects with Mariam's when a similar tragedy forces her to accept a marriage proposal from Mariam's husband.

This article deals with activities of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency related to transnational crime, including the illicit drug trade.

Crime in Iran is present in various forms, and may include the following offences: murder, kidnapping, theft, fraud, money laundering, drug trafficking, drug dealing, alcohol smuggling, oil smuggling, tax evasion, terrorism, not wearing "proper" hijab, eating and drinking during Ramadan, drinking alcohol, and many other crimes.

Shukria Barakzai is an Afghan politician, journalist and Muslim feminist. She was the ambassador of Afghanistan to Norway. She is a recipient of the International Editor of the Year Award.

Maria Bashir is a prosecutor based in Afghanistan and the only woman to ever hold such a position in the country as of 2009. With more than fifteen years of experience with Afghan civil service - the Taliban, corrupt policemen, death threats, failed assassination attempts - she has seen them all. She was banned from working during the Taliban period, when she spent her time schooling girls illegally at her residence, when it was illegal for women to be seen unescorted by men on the streets. In the post-Taliban era, she was called back into service, and was made the Chief Prosecutor General of Herat Province in 2006. With her main focus on eradicating corruption and oppression of women, she handled around 87 cases in 2010 alone.

According to UNICEF, child marriage is the "formal marriage or informal union before age 18", and it affects more girls than boys. In Afghanistan, up to 57% of girls are married before they are 19. The most common ages for girls to get married are 15 and 16. Factors such as gender dynamics, family structure, cultural, political, and economic perceptions/ideologies all play a role in determining if a girl is married at a young age.

Crime is present in various forms in Myanmar and is continuous with the activities of many drug trafficking financed militias at the eastern and western border regions, and with corruption within and challenges to the central government.

Roya Sadat is an Afghan film producer and director. She was the first woman director in the history of Afghan cinema in the post-Taliban era, and ventured into making feature films and documentaries on the theme of injustice and restrictions imposed on women. Following the fall of the Taliban regime in the country, she made her debut feature film Three Dots. For this film she received six of nine awards which included as best director and best film. In 2003,A Letter to the President her most famous film that received many international awards, she and her sister Alka Sadat established the Roya Film House and under this banner produced more than 30 documentaries and feature films and TV series. She is now involved to direct the opera of A Thousand Splendid Suns for the Seattle Opera and she is during pre production of her 2nd feature film Forgotten History.

Alka Sadat (Persian: الکا سادات, is an Afghan documentary and feature film producer, director and cameraman. She became famous with her first 25-minute film Half Value Life, which highlights social injustice and crime; the film won several awards. She is the younger sister of Roya Sadat, the first Afghan woman film producer and director. The two sisters have collaborated in many film productions from 2004 and were instrumental in establishing the Roya Film House. For her first film she received the Afghan Peace Prize and since then has made many documentaries for which she has won many international awards as a producer, cameraman, and director and also for her work in Television. Both had participated in the "Muslim World: A Short-Film Festival", organized at the Los Angeles Film School, where 32 films from Afghanistan were featured. In 2013, she coordinated in holding the first Afghanistan International Women's Film Festival. Her contribution to film making so far is in 15 documentaries and one short fiction feature film.

Laila Haidari is an Afghan activist and restaurateur. She runs Mother Camp, a drug rehabilitation centre she founded in Kabul, Afghanistan, in 2010. She also owns Taj Begum, a Kabul cafe that funds Mother Camp. Taj Begum is frequently raided because it breaks taboos; the cafe is run by a woman and allows unmarried men and women to eat together. Haidari is the subject of the 2018 documentary film Laila at the Bridge. She was recognized as one of the BBC's 100 women of 2021.

The 20-year-long War in Afghanistan had a number of significant impacts on Afghan society.