Daidō Moriyama is a Japanese photographer best known for his black-and-white street photography and association with the avant-garde photography magazine Provoke.

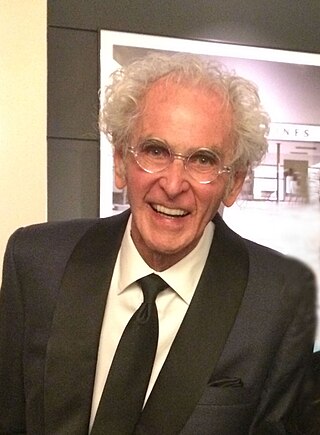

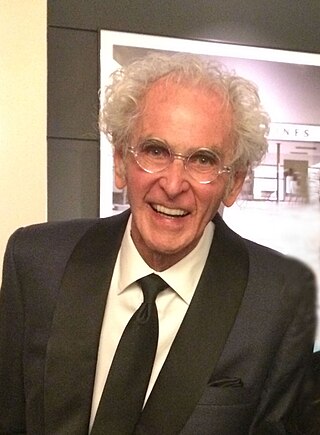

Jerry Norman Uelsmann was an American photographer.

Eikoh Hosoe is a Japanese photographer and filmmaker who emerged in the experimental arts movement of post-World War II Japan. Hosoe is best known for his dark, high contrast, black and white photographs of human bodies. His images are often psychologically charged, exploring subjects such as death, erotic obsession, and irrationality. Some of his photographs reference religion, philosophy and mythology, while others are nearly abstract, such as Man and Woman # 24, from 1960. He was professionally and personally affiliated with the writer Yukio Mishima and experimental artists of the 1960s such as the dancer Tatsumi Hijikata, though his work extends to a diversity of subjects. His photography is not only notable for its artistic influence but for its wider contribution to the reputations of his subjects.

Yasuhiro Ishimoto was a Japanese-American photographer. His decades-long career explored expressions of modernist design in traditional architecture, the quiet anxieties of urban life in Tokyo and Chicago, and the camera's capacity to bring out the abstract in the everyday and seemingly concrete fixtures of the world around him.

Yutaka Takanashi is a Japanese photographer who has photographed fashion, urban design, and city life, and is best known for his depiction of Tokyo.

Shōmei Tōmatsu was a Japanese photographer. He is known primarily for his images that depict the impact of World War II on Japan and the subsequent occupation of U.S. forces. As one of the leading postwar photographers, Tōmatsu is attributed with influencing the younger generations of photographers including those associated with the magazine Provoke.

Shigeo Anzai was a Japanese photographer. A self-professed "art documentarist", Anzai is well-known for his prolific photographic documentation of artworks, exhibitions, and events of his time. He is also known for intimate portraits of popular modern and contemporary artists, which cast their subjects in an unexpected, unposed, and humanizing light. As Anzai noted for Artforum, he was interested in the "humanity" of his subjects, or the human being within the artist, rather than the artist within the human being. Anzai's style of portraiture stands in contrast to the popular modes of portrait photography of the time which monumentalized their subjects, as in the work of Hans Namuth. Anzai is known for his snapshots of artists such as Shuzo Takiguchi, Atsuko Tanaka, Yayoi Kusama, Tetsumi Kudo, Joseph Beuys, and Isamu Noguchi, among others.

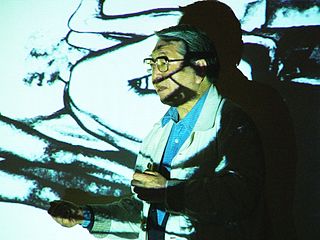

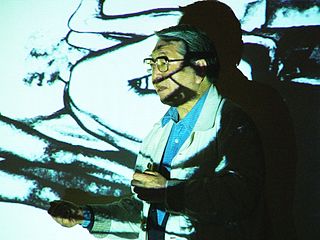

Kiyoji Ōtsuji was a Japanese photographer, photography theorist, and educator. He was active in the avant-garde art world in Japan after World War II, both creating his own experimental photographs, and taking widely circulated documentary photographs of other artists and art projects. He became an authority in Japanese photography, extensively publishing commentaries and educating future generations of photographers.

Shimooka Renjō was a Japanese photographer and was one of the first professional photographers in Japan. He opened the first commercial photography studio in Yokohama, and in Japan he is widely considered the father of Japanese photography.

Takuma Nakahira was a Japanese photographer, critic, and theorist. He was a member of the seminal photography collective Provoke, played a central role in developing the theorization of landscape discourse (fūkei-ron), and was one of the most prominent voices in 1970s Japanese photography.

Jawshing Arthur Liou is a digital artist whose work depicts spaces not probable in reality. Working with both lens-based representation and digital post-production, he aims to transform recognizable imagery into realms of transcendent and otherworldly experience.

Glenn Rand is an American photographic artist, educator and writer. He has produced photographic art that has been included in public museum collections throughout the United States, Japan, and Europe. He has written twelve books on photography and contributed regularly to magazines. In 2009, the Photo Imaging Education Association (PIEA) presented him with its "Excellence in Education Award" for his insightful contributions to photographic education.

Austin Irving is an American contemporary artist and photographer.

MaoIshikawa is an Okinawan photographer and activist. Her photographs largely feature bar girls, performers, soldiers, and other fringe members within Okinawan and Japanese society. Ishikawa's earlier works are characterized by her approach to photography which involved the photographer's immersion in the environment of her images, whether by living with her subject or working in close proximity to them. In her photographs of active soldiers and military bases both in and outside of Japan beginning from the 1990s, Ishikawa has more directly addressed political undercurrents, namely contempt for the U.S. military presence in Okinawa and distrust of the Japanese government. Her most recent series Great Ryukyu Photo Scroll (大琉球写真絵巻) (2014-) approaches the same themes through a narrative tone, using satire and pop culture references to reconstruct important moments in Okinawan history.

Kenshichi Heshiki was an Okinawan photographer. He is known for his dedication to the subject of Okinawa and often photographed quiet scenes of Okinawans who lived on the margins of society. Heshiki's understated photographs of daily life in Okinawa have been differentiated from images taken by mainland photographers who visited the islands to shoot the protests and tension surrounding Okinawa's reversion back under Japanese control. Heshiki was most prolific between the late 1960s to the 1990s during which he travelled to and photographed various remote areas within the Ryukyu Archipelago. These images feature in his seminal book Lungs of a Goat which earned him the prestigious Ina Nobuo Award.

Ryuichi Ishikawa is an Okinawan photographer. In his youth, Ishikawa suffered from depression, leading him to withdraw from mainstream society and turn towards the alternative, underground communities that later became frequent subjects in his photography. Ishikawa serendipitously found photography and photograms in his twenties which he used to document his immediate surroundings and visualize his emotions and dreams. As his practice developed under the guidance of his mentor Tetsushi Yuzaki, Ishikawa increasingly saw photography as a means to both communicate with the outside world and find meaning in life.

Futoshi Miyagi is an Okinawan artist and writer. He works in various mediums, such as photography, objects, video and text, to construct narratives on the subjects of sexual minorities and untold stories in history, often in relation to Okinawa. Much of Miyagi's earlier work is inspired by his own memories and coming to terms with his identity as a gay Okinawan man. Over the course of his career, Miyagi has increasingly expanded the range of his subjects to include imagined characters and historical figures. Miyagi is most known for his American Boyfriend Series, an ongoing project that addresses the topic of queer relationships through narrative form. The series, a culmination of Miyagi's multidisciplinary approach, consists of a blog, numerous video works, and a novel, and mimics the evolution of his oeuvre from semi-autobiographical to historically based fiction. Miyagi takes influences from a wide range of arts and media, including the work of feminist writers and artists Lucy Lippard and Mierle Laderman Ukeles, contemporary artists Félix González-Torres and Ryan McGinley, and classical composers Bach and Beethoven. For his photographs and video work, Miyagi has been recognized as a finalist for the Kimura Ihei Award and the Nissan Art Award.

Yasuo Higa was an Okinawan photographer, ethnologist and anthropologist. He served ten years as a police officer near a US military base before becoming a photographer, with much of his early work centered on life in postwar Okinawa. Higa is most known for his research on ancient rituals and shamanesses from the Ryukyu Islands, mainland Japan, and Asia, conducted over the span of nearly 40 years. Through his photographs and extensive notes, Higa has preserved critical documentation on maternal rituals that have been effectively rendered extinct in areas such as Kudaka and Miyakojima.

Osamu Shiihara (椎原治) was a Japanese photographer born on 3 October 1905 in Osaka City.

Ryūichi Kaneko was a photography historian and critic, photobook collector, and curator. He also worked as a monk at the Shōgyōin temple in the Taitō district of Tokyo while he researched the history of Japanese photography.