Related Research Articles

Owain ap Gruffudd was King of Gwynedd, North Wales, from 1137 until his death in 1170, succeeding his father Gruffudd ap Cynan. He was called Owain the Great and the first to be styled "Prince of Wales", and the "Prince of the Welsh". He is considered to be the most successful of all the North Welsh princes prior to his grandson, Llywelyn the Great. He became known as Owain Gwynedd to distinguish him from the contemporary king of Powys Wenwynwyn, Owain ap Gruffydd ap Maredudd, who became known as Owain Cyfeiliog.

Maelgwn Gwynedd was king of Gwynedd during the early 6th century. Surviving records suggest he held a pre-eminent position among the Brythonic kings in Wales and their allies in the "Old North" along the Scottish coast. Maelgwn was a generous supporter of Christianity, funding the foundation of churches throughout Wales and even far beyond the bounds of his own kingdom. Nonetheless, his principal legacy today is the scathing account of his behavior recorded in De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae by Gildas, who considered Maelgwn a usurper and reprobate. The son of Cadwallon Lawhir and great-grandson of Cunedda, Maelgwn was buried on Ynys Seiriol, off the eastern tip of Anglesey, having died of the "yellow plague"; quite probably the arrival of Justinian's Plague in Britain.

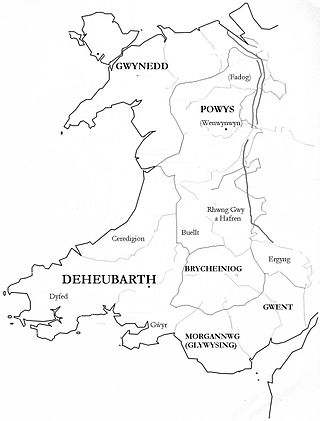

Deheubarth was a regional name for the realms of south Wales, particularly as opposed to Gwynedd. It is now used as a shorthand for the various realms united under the House of Dinefwr, but that Deheubarth itself was not considered a proper kingdom on the model of Gwynedd, Powys, or Dyfed is shown by its rendering in Latin as dextralis pars or as Britonnes dexterales and not as a named land. In the oldest British writers, Deheubarth was used for all of modern Wales to distinguish it from Hen Ogledd, the northern lands whence Cunedda originated.

The Kingdom of Gwynedd was a Welsh kingdom and a Roman Empire successor state that emerged in sub-Roman Britain in the 5th century during the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain.

Cunedda ap Edern, also called Cunedda Wledig, was an important early Welsh leader, and the progenitor of the Royal dynasty of Gwynedd, one of the very oldest of Western Europe.

Cadwallon is a Welsh name derived from the Common Brittonic *Katuwellaunos "The One Who (-mnos) Leads (welnā-) in Battle (katu-)". The same name belonged to the Catuvellauni who lived in what is now Hertfordshire, one of the most powerful British polities in the Late Iron Age who led the resistance against the Romans in 43 CE and possibly against Caesar in 55 and 54 BCE as well.

Beli ap Rhun was King of Gwynedd. Nothing is known of the person, and his name is known only from Welsh genealogies, which confirm that he had at least two sons. He succeeded his father Rhun ap Maelgwn as king, and was in turn succeeded by his son Iago. Beli was either the father or grandfather of Saint Edeyrn.

Rhun ap Maelgwn Gwynedd, also known as Rhun Hir ap Maelgwn Gwynedd, sometimes spelt as 'Rhûn', was King of Gwynedd. He came to the throne on the death of his father, King Maelgwn Gwynedd. There are no historical records of his reign in this early age. A story preserved in both the Venedotian Code and an elegy by Taliesin says that he waged a war against Rhydderch Hael of Alt Clut and the kings of Gododdin or Manaw Gododdin. The small scattered settlement of Caerhun in the Conwy valley is said to be named for him, though without strong authority. Rhun also appears in several medieval literary stories, as well as in the Welsh Triads. His wife was Perwyr ferch Rhûn "Ryfeddfawr" and their son was Beli ap Rhun "Hîr".

Einion Yrth ap Cunedda, also known as Einion Yrth, was a king of Gwynedd. He is claimed as an ancestor of the later rulers of North Wales.

Cadwallon Lawhir ap Einion, usually known as Cadwallon Lawhir and also called Cadwallon I by some historians, was a king of Gwynedd around 500.

The Castle of Dinerth is a Welsh castle located near Aberarth, Ceredigion, west Wales that was completed c. AD 1110. It is also known as Hero Castle, presumably from the Norse hiro.

Maredudd ab Owain was a 10th-century king in Wales of the High Middle Ages. A member of the House of Dinefwr, his patrimony was the kingdom of Deheubarth comprising the southern realms of Dyfed, Ceredigion, and Brycheiniog. Upon the death of his father King Owain around AD 988, he also inherited the kingdoms of Gwynedd and Powys, which he had conquered for his father. He was counted among the Kings of the Britons by the Chronicle of the Princes.

Maelienydd, sometimes spelt Maeliennydd, was a cantref and lordship in east central Wales covering the area from the River Teme to Radnor Forest and the area around Llandrindod Wells. The area, which is mainly upland, is now in Powys. During the Middle Ages it was part of the region known as Rhwng Gwy a Hafren and its administrative centre was at Cefnllys Castle.

Cuneglasus was a prince of Rhos in Gwynedd, Wales, in the late 5th or early 6th century. He was castigated for various sins by Gildas in De Excidio Britanniae. The Welsh form Cynlas Goch is attested in several genealogies of the Rhos royal line. The two names are assumed to refer to the same ruler.

Cadwallon ap Madog was the son of Madog ab Idnerth who had died in 1140, while Idnerth was a grandson of Elystan Glodrydd who had died in around 1010 and had founded a dynasty in the Middle Marches of Wales, in the area known as Rhwng Gwy a Hafren.

Elfael was one of a number of Welsh cantrefi occupying the region between the River Wye and river Severn, known as Rhwng Gwy a Hafren, in the early Middle Ages. It was divided into two commotes, Is Mynydd and Uwch Mynydd, separated by the chain of hills above Aberedw. In the late medieval period, it was a marcher lordship. However, after the Laws in Wales Act 1535, it was one of the territorial units which went to make up the county of Radnorshire in 1536.

Einion, the Welsh form of the Latin Ennianus, is a male Welsh given name and may refer to:

Saint Einion Frenin was a late 5th and early 6th century Welsh confessor and saint of the Celtic Church. His feast day was originally given as 9 February, although this had moved to the 10th or 12th by the 16th century and is no longer observed by either the Anglican or Catholic church in Wales.

References

- 1 2 Bartrum, Peter (1993). "Owain Danwyn ab Einion Yrth". A Welsh Classical Dictionary: People in History and Legend up to about A.D. 1000 (PDF). National Library of Wales. p. 594. ISBN 0907158730.

- ↑ Bartrum, Peter (1993). "Cadwallon Lawhir ap Einion Yrth". A Welsh Classical Dictionary: People in History and Legend up to about A.D. 1000 (PDF). National Library of Wales. p. 94. ISBN 0907158730.

- ↑ Bartrum, Peter (1993). "Maelgwn Gwynedd". A Welsh Classical Dictionary: People in History and Legend up to about A.D. 1000 (PDF). National Library of Wales. p. 500. ISBN 0907158730.

- ↑ Graham Phillips and Martin Keatman; King Arthur: The True Story, Century, 1992.

- ↑ Wood, Charles T. (Fall 1995). "Reviewed Works: From Scythia to Camelot: A Radical Reassessment of the Legends of King Arthur, the Knights of the Round Table and the Holy Grail, by C. Scott Littleton and Linda A. Malcor; and King Arthur: The True Story by Graham Phillips and Martin Keatman". Arthuriana . 5 (3). doi:10.1353/art.1995.0033. JSTOR 27869131.

- ↑ Castleden, Rodney (2003). King Arthur: The Truth Behind the Legend. Routledge. p. 124. ISBN 1134373775.