Related Research Articles

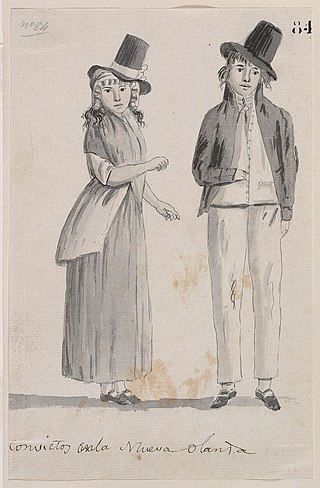

Penal transportation was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies became their destination. While the prisoners may have been released once the sentences were served, they generally did not have the resources to return home.

York is the oldest inland town in Western Australia, situated on the Avon River, 97 kilometres (60 mi) east of Perth in the Wheatbelt, on Ballardong Nyoongar land, and is the seat of the Shire of York.

Convict assignment was the practice used in many penal colonies of assigning convicts to work for private individuals. Contemporary abolitionists characterised the practice as virtual slavery, and some, but by no means all, latter-day historians have agreed with this assessment.

The convict era of Western Australia was the period during which Western Australia was a penal colony of the British Empire. Although it received small numbers of juvenile offenders from 1842, it was not formally constituted as a penal colony until 1849. Between 1850 and 1868, 9,721 convicts were transported to Western Australia on 43 convict ship voyages. Transportation ceased in 1868, at which time convicts outnumbered free settlers 9,700 to 7,300, and it was many years until the colony ceased to have any convicts in its care.

HM Prison Parkhurst is a Category B men's prison located in Parkhurst on the Isle of Wight, and is operated by His Majesty's Prison Service. Parkhurst prison is one of two former separate prisons that today make up HMP Isle of Wight, the other being Albany.

Between 1788 and 1868 the British penal system transported about 162,000 convicts from Great Britain and Ireland to various penal colonies in Australia.

John Williams was a convict transported to Van Diemen's Land. He is best known as the man with whom Joseph Johns, later to become the bushranger Moondyne Joe, was arrested and tried for burglary.

Scindian is widely considered the first convict ship to transport convicts to Western Australia. She was launched in 1844 and sank in 1880.

Simon Taylor was a barque built in 1824 on the River Thames that transported assisted migrants to Western Australia.

Tranby (Peninsula Farm) is an historic farmers cottage located on Johnson Road in Maylands overlooking the Swan River opposite Kuljak Island, and is one of the oldest surviving buildings from the early settlement of the Swan River Colony. It is described as an English cottage-style farmhouse with loft bedrooms and wide verandahs and is associated with a group of devout Wesleyan Methodists, led by Joseph Hardey and other members of his family, who arrived in Western Australia on the ship Tranby in February 1830.

The Newcastle Gaol Museum is a prison museum on Clinton Street in Toodyay, Western Australia, founded in 1962. The museum records the history of the serial escapee Moondyne Joe and his imprisonment in the "native cell".

Joseph Backler was an English-born Australian painter. Transported to Australia as a convict in 1832, he obtained a ticket of leave in 1842 and was active as a painter from 1842 to 1880.

The Fremantle School building is a heritage-listed building located at 92 Adelaide Street, Fremantle. It was known for a long time by the name of its later occupants, the Film and Television Institute.

John Acton Wroth (1830–1876) was a convict transportee to the Swan River Colony, and later a clerk and storekeeper in Toodyay, Western Australia. He kept a personal diary that recorded life on board the transport ship and his experiences at the country hiring depots of York and Toodyay. This diary is lodged in the archives of the State Library.

George Hall Esq. was a British administrator in the 19th century.

The New Zealand Company was a 19th-century English company that played a key role in the colonisation of New Zealand. The company was formed to carry out the principles of systematic colonisation devised by Edward Gibbon Wakefield, who envisaged the creation of a new-model English society in the southern hemisphere. Under Wakefield's model, the colony would attract capitalists who would then have a ready supply of labour—migrant labourers who could not initially afford to be property owners, but who would have the expectation of one day buying land with their savings.

Rev. John Whitelaw Schoales (1820–1903) was an Anglican priest in the pioneering days of Adelaide, South Australia.

Walter Boyd Andrews was an early settler in Perth, Western Australia and, briefly, a non-official member of the colony's Legislative Council.

Walkinshaw Cowan was private secretary to Western Australian Governors John Hutt, Andrew Clarke and Frederick Irwin, then in 1848 he became Guardian of Aboriginals and a justice of the peace, and then resident magistrate at York from 1863 to 1887.

References

- ↑ Gill (2004), page 1: "Once in the colony, they were pardoned on two conditions..."

- ↑ Statham (1981), page 6" "... these boys had received conditional pardons prior to leaving England..."

- ↑ Robbins, W.M. review of Gill's (2004) Convict Assignment at "| Book Review | Labour History, 88 | the History Cooperative". Archived from the original on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2010. (vol 88. May 2005) 'In short, Gill argues that convict transportation to WA arrived in a disguised form and at an earlier time than is commonly thought. Between 1842 and 1852 Gill finds that 243 young British juvenile offenders were transported to WA even though officially they were described as 'apprentices' '

- ↑ "Advertising". The Inquirer . No. 350. Western Australia. 14 April 1847. p. 2. Retrieved 6 April 2019– via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Papers in Labour History No.6" (PDF). Department of Industrial Relations, University of Western Australia. p. 3. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ↑ Anthony G. Flude (2003). "CONVICTS SENT TO NEW ZEALAND! The Boys from Parkhurst Prison". Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ↑ "Memorial by the Colonists of South Australia against the Introduction of Convicts". The South Australian . Vol. VIII, no. 600. South Australia. 14 February 1845. p. 2. Retrieved 15 November 2016– via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Francesca Ashurst; Couze Venn (7 February 2014). Inequality, Poverty, Education: A Political Economy of School Exclusion. Springer. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-1137347015 . Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ↑ "Parkhurst Boys – Thomas Arbuthnot 1847". Convicts to Australia. Perth Dead Persons' Society. 2003. Retrieved 18 December 2006.