Chiricahua is a band of Apache Native Americans.

Globe is a city in Gila County, Arizona, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 7,249. The city is the county seat of Gila County. Globe was founded c. 1875 as a mining camp. Mining, tourism, government and retirees are most important in the present-day Globe economy.

The Apache Wars were a series of armed conflicts between the United States Army and various Apache tribal confederations fought in the southwest between 1849 and 1886, though minor hostilities continued until as late as 1924. After the Mexican–American War in 1846, the United States annexed conflicted territory from Mexico which was the home of both settlers and Apache tribes. Conflicts continued as American settlers came into traditional Apache lands to raise livestock and crops and to mine minerals.

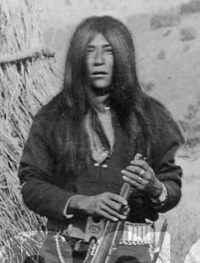

Massai was a member of the Mimbres/Mimbreños local group of the Chihenne band of the Chiricahua Apache. He was a warrior who was captured but escaped from a train that was sending the scouts and renegades to Florida to be held with Geronimo and Chihuahua.

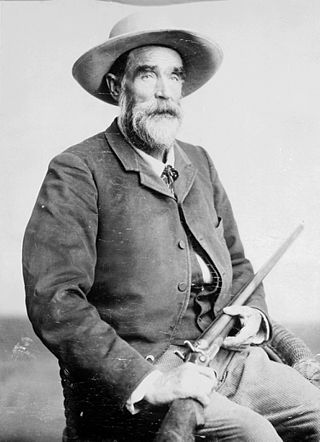

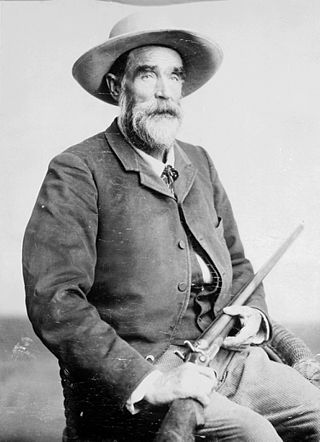

Thomas Jefferson Jeffords was a United States Army scout, Indian agent, prospector, and superintendent of overland mail in the Arizona Territory. His friendship with Apache leader Cochise was instrumental in ending the Indian wars in that region. He first met Cochise when he rode alone into Cochise's camp in 1871 to request that the chief come to Canada Alamosa for peace talks. Cochise declined at least in part because he was afraid to travel with his family after the recent Camp Grant Massacre. Three months later he made the trip and stayed for over six months during which time their friendship grew while the negotiations failed. Cochise was unwilling to accept the Tularosa Valley as his reservation and home. In October 1872, Jeffords led General Oliver O. Howard to Cochise's Stronghold, believed to be China Meadow, in the Dragoon Mountains. Cochise demanded and got the Dragoon and Chiricahua Mountains as his reservation and Tom Jeffords as his agent. From 1872 to 1876, there was peace in southern Arizona. Then renegade Apaches killed Nicholas Rogers who had sold them whiskey and the cry went out to abolish the reservation and remove Jeffords as agent. Tom Jeffords embarked on a series of ventures as sutler and postmaster at Fort Huachuca, head of the first Tucson water company trying to bring artesian water to that city, and as prospector and mine owner and developer. He died at Owl Head Buttes in the Tortolita Mountains 35 miles north of Tucson.

The Apache Scouts were part of the United States Army Indian Scouts. Most of their service was during the Apache Wars, between 1849 and 1886, though the last scout retired in 1947. The Apache scouts were the eyes and ears of the United States military and sometimes the cultural translators for the various Apache bands and the Americans. Apache scouts also served in the Navajo War, the Yavapai War, the Mexican Border War and they saw stateside duty during World War II. There has been a great deal written about Apache scouts, both as part of United States Army reports from the field and more colorful accounts written after the events by non-Apaches in newspapers and books. Men such as Al Sieber and Tom Horn were sometimes the commanding officers of small groups of Apache Scouts. As was the custom in the United States military, scouts were generally enlisted with Anglo nicknames or single names. Many Apache Scouts received citations for bravery.

Al Sieber was a German-American immigrant who fought in the American Civil War (1861-1865), and in the American Old West frontier against the Native Americans. (Indians) in the later American Indian Wars of the mid to late 19th century. He became a prospector and later served as a decorated Chief of Scouts for the United States Army dring the subsequent Apache Wars of 1849 - 1886 in the southwestern United States.

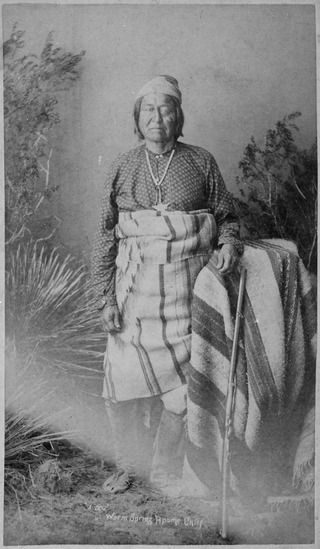

Loco was a Copper Mines Mimbreño Apache chief who was known for seeking peace at all costs with the US Army, despite the outlook of his fellow Apaches like Victorio and Geronimo.

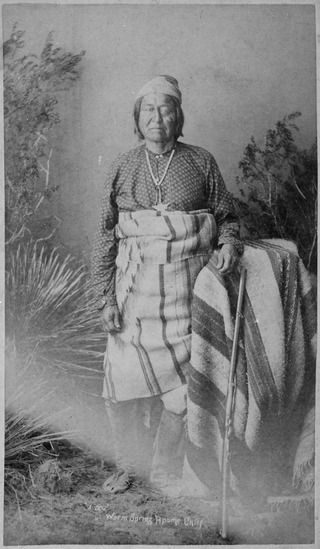

The Fort Sill Apache Tribe of Oklahoma is the federally recognized Native American tribe of Chiricahua Warm Springs Apache in Oklahoma.

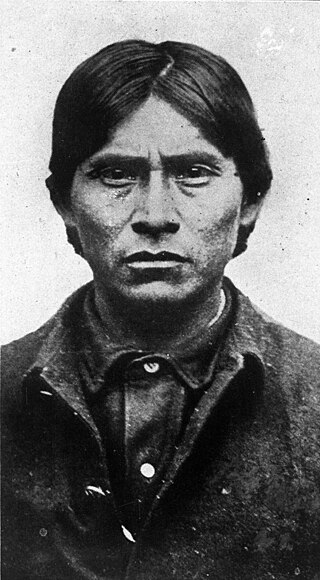

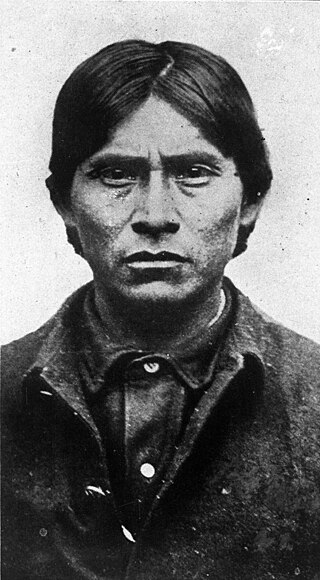

Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl, better known as the Apache Kid, was born in Aravaipa Canyon, 25 miles south of San Carlos Agency, into one of the three local groups of the Aravaipa/Arivaipa Apache Band of San Carlos Apache, one subgroup of the Western Apache people. As a member of what the U.S. government called the "SI band", Kid developed important skills and became a famous and respected scout and later a notorious renegade active in the borderlands of the U.S. states of Arizona and New Mexico in the late 19th and possibly the early 20th centuries.

Victorio's War, or the Victorio Campaign, was an armed conflict between the Apache followers of Chief Victorio, the United States, and Mexico beginning in September 1879. Faced with arrest and forcible relocation from his homeland in New Mexico to San Carlos Indian Reservation in southeastern Arizona, Victorio led a guerrilla war across southern New Mexico, west Texas and northern Mexico. Victorio fought many battles and skirmishes with the United States Army and raided several settlements until the Mexican Army killed him and most of his warriors in October 1880 in the Battle of Tres Castillos. After Victorio's death, his lieutenant Nana led a raid in 1881.

The Kelvin Grade massacre was an incident that occurred on November 2, 1889 when a group of nine imprisoned Apache escaped from police custody during a prisoner transfer near the town of Globe, Arizona. The escape resulted in the deaths of two sheriffs and triggered one of the largest manhunts in Arizona history. Veterans of the Apache Wars scoured the Arizona frontier for nearly a year in search of the fugitives, by the end of which all were caught or killed except for the famous Indian scout known as the Apache Kid.

Glenn Reynolds was an American sheriff, cowboy, and militiaman of the Old West, remembered for his death during the Kelvin Grade Massacre, in Arizona Territory, when a group of Apache renegades escaped from his custody.

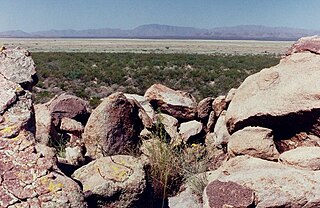

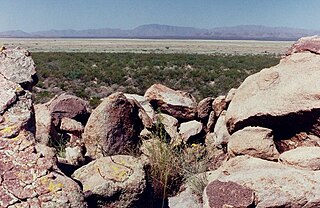

The Cherry Creek campaign occurred in March 1890 and was one of the final conflicts between hostile Apaches and the United States Army. It began after a small group of Apaches killed a freight wagon operator, near the San Carlos Reservation, and was part of the larger Apache campaign, beginning in 1889, to round up Apaches who had left the reservations. The American army fought a skirmish with the Apaches near Globe, Arizona, at the mouth of Cherry Creek, which resulted in the deaths of two hostiles and the capture of the remaining three. Two men received the Medal of Honor for their service during the campaign.

The Apache Campaign of 1896 was the final United States Army operation against Apaches who were raiding and not living in a reservation. It began in April after Apache raiders killed three white American settlers in the Arizona Territory. The Apaches were pursued by the army, which caught up with them in the Four Corners region of Arizona, New Mexico, Sonora and Chihuahua. There were only two important encounters during the campaign and, because both of them occurred in the remote Four Corners region, it is unknown if they took place on American or Mexican soil.

Clay Beauford was an American army officer, scout and frontiersman. An ex-Confederate soldier in his youth, he later enlisted in the U.S. Army and served with the 5th U.S. Cavalry during the Indian Wars against the Plains Indians from 1869 to 1873. He acted as a guide for Lieutenant Colonel George Crook in his "winter campaign" against the Apaches and received the Medal of Honor for his conduct.

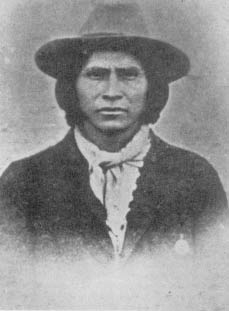

Mickey Free, birth name Felix Telles, was an Apache Indian scout and bounty hunter on the American frontier. Following his kidnapping by Apaches as a child, he was raised as one and became a warrior. Later he joined the US Army's Apache scouts, serving at Fort Verde between December 1874 and May 1878 and was given the nickname Mickey Free.

Alsate, also known as Arzate, Arzatti, and Pedro Múzquiz, was the last chief of the Chisos band of Limpia Mescalero Apaches.

First Lieutenant Britton Davis was an American soldier born in Brownsville, Texas. He served in the United States Army in the 6th Cavalry after graduating from West Point in 1881. After serving at Fort D.A. Russell, Davis was transferred to the Southwest to serve at San Carlos in 1882 during the Apache Wars where he commanded two companies of Apache Scouts alongside Captain Emmet Crawford. In 1886, he played a key role in ending the Geronimo Campaign.

The Battle of Tres Castillos, October 14–15, 1880, in Chihuahua State, Mexico resulted in the death of the Chiricahua Apache chieftain Victorio and the death or capture of most of his followers. The battle ended Victorio's War, a 14-month long odyssey of fight and flight by the Apaches in southern New Mexico, western Texas, and Chihuahua. Mexican Colonel Joaquin Terrazas and 260 men surrounded the Apache and killed 62 men, including Victorio, and 16 women and children, and captured 68 women and children. Three Mexicans were killed. Victorio had little ammunition to resist the attack.