Frans Masereel was a Flemish painter and graphic artist who worked mainly in France, known especially for his woodcuts focused on political and social issues, such as war and capitalism. He completed over 40 wordless novels in his career, and among these, his greatest is generally said to be Passionate Journey.

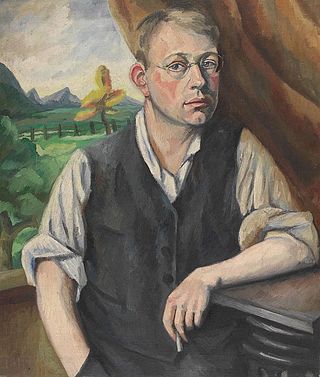

Lynd Kendall Ward was an American artist and novelist, known for his series of wordless novels using wood engraving, and his illustrations for juvenile and adult books. His wordless novels have influenced the development of the graphic novel. Although strongly associated with his wood engravings, he also worked in watercolor, oil, brush and ink, lithography and mezzotint. Ward was a son of Methodist minister, political organizer and radical social activist Harry F. Ward, the first chairman of the American Civil Liberties Union on its founding in 1920.

Song Without Words: A Book of Engravings on Wood is a wordless novel of 1936 by American artist Lynd Ward (1905–1985). Executed in twenty-one wood engravings, it was the fifth and shortest of the six wordless novels Ward completed, produced while working on the last and longest, Vertigo (1937). The story concerns the anxiety an expectant mother feels over bringing a child into a world under the threat of fascism—anxieties Ward and writer May McNeer were then feeling over McNeer's pregnancy with the couple's second child.

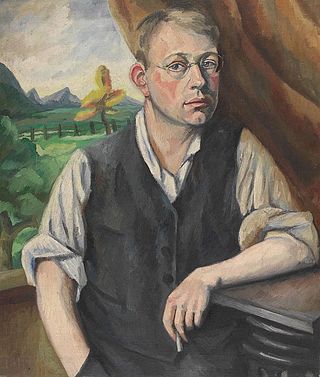

Otto Nückel was a German painter, graphic designer, illustrator and cartoonist. He is best known as one of the 20th century's pioneer wordless novelists, along with Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward.

Helena Bochořáková-Dittrichová was a Czech illustrator, graphic novelist, and later a painter. She is widely acknowledged as being the first female graphic novelist.

He Done Her Wrong is a wordless novel written by American cartoonist Milt Gross and published in 1930. It was not as successful as some of Gross's earlier works, notably his book Nize Baby (1926) based on his newspaper comic strips. He Done Her Wrong has been reprinted in recent years and is now recognized as a comic parody of other similar wordless novels of the early 20th century, as well as an important precursor to the modern graphic novel.

The wordless novel is a narrative genre that uses sequences of captionless pictures to tell a story. As artists have often made such books using woodcut and other relief printing techniques, the terms woodcut novel or novel in woodcuts are also used. The genre flourished primarily in the 1920s and 1930s and was most popular in Germany.

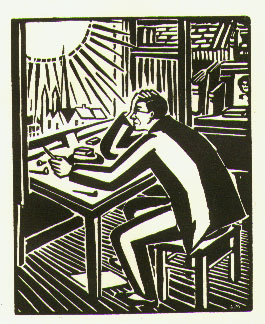

Gods' Man is a wordless novel by American artist Lynd Ward (1905–1985) published in 1929. In 139 captionless woodblock prints, it tells the Faustian story of an artist who signs away his soul for a magic paintbrush. Gods' Man was the very first American wordless novel, and is considered a precursor of the graphic novel, whose development it influenced.

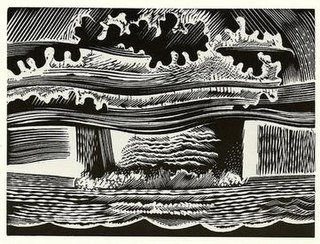

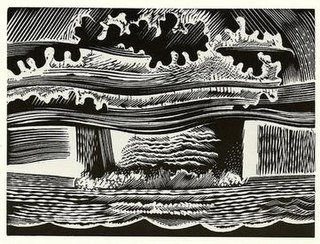

Southern Cross is the sole wordless novel by Canadian artist Laurence Hyde (1914–1987). Published in 1951, its 118 wood-engraved images narrate the impact of atomic testing on Pacific islanders. Hyde made the book to express his anger at the US military's nuclear tests in the Bikini Atoll.

25 Images of a Man's Passion, or The Passion of a Man is the first wordless novel by Flemish artist Frans Masereel (1889–1972), first published in 1918 under the French title 25 images de la passion d'un homme. The silent story is about a young working-class man who leads a revolt against his employer. The first of dozens of such works by Masereel, the book is considered to be the first wordless novel, a genre that saw its greatest popularity in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. Masereel followed the book in 1919 with his best-known work, Passionate Journey.

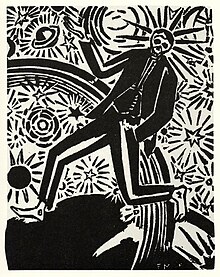

The Idea is a 1920 wordless novel by Flemish artist Frans Masereel (1889–1972). In eighty-three woodcut prints, the book tells an allegory of a man's idea, which takes the form of a naked woman who goes out into the world; the authorities try to suppress her nakedness, and execute a man who stands up for her. Her image is spread through the mass media, inciting a disruption of the social order. Filmmaker Berthold Bartosch made an animated adaptation in 1932.

The Idea is a 1932 French animated film by Austro-Hungarian filmmaker Berthold Bartosch (1893–1968), based on the 1920 wordless novel of the same name by Flemish artist Frans Masereel (1889–1972). The protagonist is a naked woman who represents a thinker's idea; as she goes out into the world, the frightened authorities unsuccessfully try to cover up her nudity. A man who stands up for her is executed, and violent suppression by big business greets a workers' revolution she inspires.

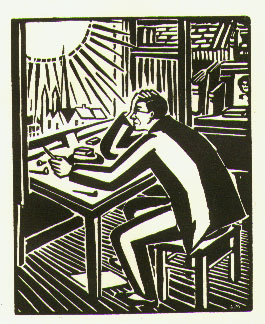

Prelude to a Million Years: A Book of Wood Engravings is a 1933 wordless novel consisting of thirty wood engravings by American artist Lynd Ward (1905–1985). It was the fourth of Ward's six wordless novels, a genre Ward discovered while studying wood engraving in Europe, and delved into under the influence of the works of Frans Masereel and Otto Nückel. The symbol-rich story tells of a sculptor who, in his quest for ideal beauty, neglects the reality of the struggles of his neighbors in the depths of the Great Depression. The engravings are done in a softer Art Deco style in contrast to the German Expressionism-influenced artwork of Ward's earlier works.

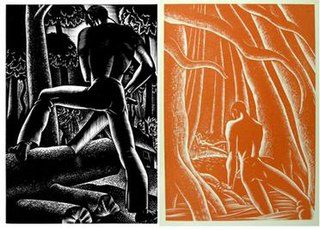

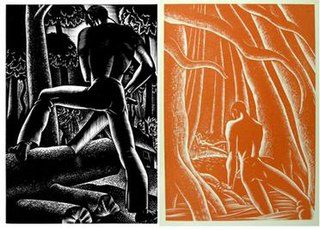

Wild Pilgrimage is the third wordless novel of American artist Lynd Ward (1905–1985), published in 1932. It was executed in 108 monochromatic wood engravings, printed alternately in black ink when representing reality and orange to represent the protagonist's fantasies. The story tells of a factory worker who abandons his workplace to seek a free life; on his travels he witnesses a lynching, assaults a farmer's wife, educates himself with a hermit, and upon returning to the factory leads an unsuccessful workers' revolt. The protagonist finds himself battling opposing dualities such as freedom versus responsibility, the individual versus society, and love versus death.

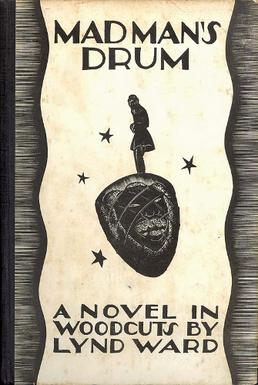

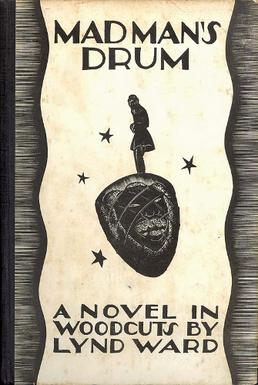

Madman's Drum is a wordless novel by American artist Lynd Ward (1905–1985), published in 1930. It is the second of Ward's six wordless novels. The 118 wood-engraved images of Madman's Drum tell the story of a slave trader who steals a demon-faced drum from an African he murders, and the consequences for him and his family.

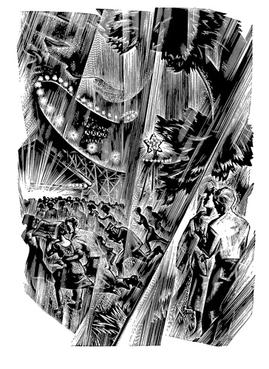

Vertigo is a wordless novel by American artist Lynd Ward (1905–1985), published in 1937. In three intertwining parts, the story tells of the effects the Great Depression has on the lives of an elderly industrialist and a young man and woman. Considered his masterpiece, Ward uses the work to express the socialist sympathies of his upbringing; he aimed to present what he called "impersonal social forces" by depicting the individuals whose actions are responsible for those forces.

Destiny is the only wordless novel by German artist Otto Nückel. It first appeared in 1926 from the Munich-based publisher Delphin-Verlag. In 190 wordless images the story follows an unnamed woman in a German city in the early 20th century whose life of poverty and misfortune drives her to infanticide, prostitution, and murder.

The Sun is a wordless novel by Flemish artist Frans Masereel (1889–1972), published in 1919. In sixty-three uncaptioned woodcut prints, the book is a contemporary retelling of the Greek myth of Icarus.

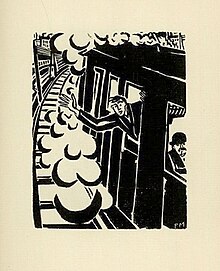

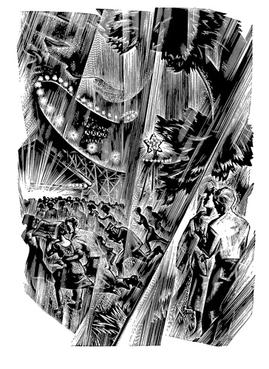

The City is a 1925 wordless novel by Flemish artist Frans Masereel. In 100 captionless woodcut prints Masereel looks at many facets of life in a big city.

Story Without Words, is a wordless novel of 1920 by Flemish artist Frans Masereel. In 60 captionless woodcut prints the story tells of a man who strives to win the love of a woman.