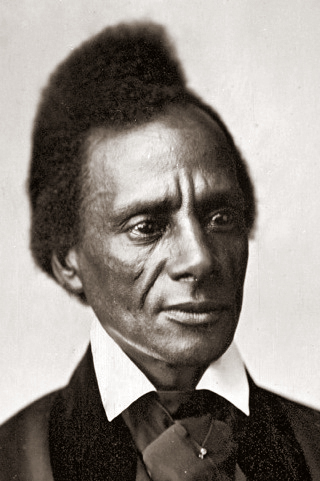

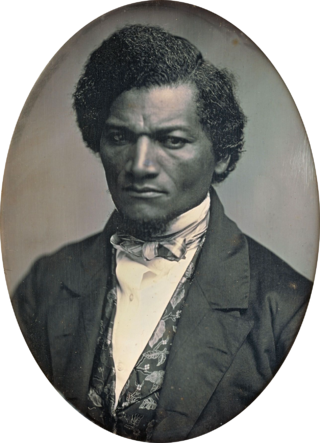

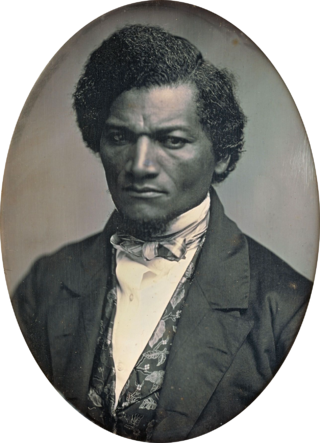

Frederick Douglass was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He became the most important leader of the movement for African-American civil rights in the 19th century.

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal was an American writer and public intellectual known for his acerbic epigrammatic wit. His novels and essays interrogated the social and sexual norms he perceived as driving American life. Vidal was heavily involved in politics, and unsuccessfully sought office twice as a Democratic Party candidate, first in 1960 to the United States House of Representatives, and later in 1982 to the United States Senate.

Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U.S., and is said to have "helped lay the groundwork for the [American] Civil War".

Highland Beach is a town in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, United States. Per the 2020 census, the population was 118. The town was founded late in the 19th century by affluent African Americans from Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, looking for a summer retreat on the Chesapeake Bay. The town's incorporated status gave it a unique standing in empowering it to maintain its own police force. Celebrities with homes there have included historian and author Alex Haley, actor and comedian Bill Cosby, and tennis champion Arthur Ashe. Street names in the town include Crummell, Dunbar, Henson, Augusta, Douglass, Langston, and Washington, which were chosen to honor leading African Americans.

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe was an American author and abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and wrote the popular novel Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), which depicts the harsh conditions experienced by enslaved African Americans. The book reached an audience of millions as a novel and play, and became influential in the United States and in Great Britain, energizing anti-slavery forces in the American North, while provoking widespread anger in the South. Stowe wrote 30 books, including novels, three travel memoirs, and collections of articles and letters. She was influential both for her writings as well as for her public stances and debates on social issues of the day.

Edmund Wilson Jr. was an American writer, literary critic and journalist. He is widely regarded as one of the most important literary critics of the 20th century. Wilson began his career as a journalist, writing for publications such as Vanity Fair and The New Yorker. He helped to edit The New Republic, served as chief book critic for The New Yorker, and was a frequent contributor to The New York Review of Books.

Henry Steele Commager was an American historian. As one of the most active and prolific liberal intellectuals of his time, with 40 books and 700 essays and reviews, he helped define modern liberalism in the United States.

Charles Lenox Remond was an American orator, activist and abolitionist based in Massachusetts. He lectured against slavery across the Northeast, and in 1840 traveled to the British Isles on a tour with William Lloyd Garrison. During the American Civil War, he recruited blacks for the United States Colored Troops, helping staff the first two units sent from Massachusetts. From a large family of African-American entrepreneurs, he was the brother of Sarah Parker Remond, also a lecturer against slavery.

Charles Bruce Catton was an American historian and journalist, known best for his books concerning the American Civil War. Known as a narrative historian, Catton specialized in popular history, featuring interesting characters and historical vignettes, in addition to the basic facts, dates, and analyses. His books were researched well and included footnotes. He won the Pulitzer Prize for History and the National Book Award for Nonfiction in 1954 for his book A Stillness at Appomattox (1953), a study of the final campaign of the war in Virginia and third book in his Army of the Potomac trilogy.

Frederick Goddard Tuckerman was an American poet, remembered mostly for his sonnet series. Apart from the 1860 publication of his book Poems, which included approximately two-fifths of his lifetime sonnet output and other poetic works in a variety of forms, the remainder of his poetry was published posthumously in the 20th century. Attempts by several 20th century scholars and critics to spark wider interest in his life and works have met with some success and Tuckerman is now included in several important anthologies of American poetry. Though his works appear in 19th century anthologies of American poetry and sonnets, this reclusive contemporary of Emily Dickinson, sometime correspondent of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and acquaintance of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, remains in relative obscurity.

The Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, administered by the National Park Service, is located at 1411 W Street, SE, in Anacostia, a neighborhood east of the Anacostia River in Southeast Washington, D.C. United States. Established in 1988 as a National Historic Site, the site preserves the home and estate of Frederick Douglass, one of the most prominent African Americans of the 19th century. Douglass lived in this house, which he named Cedar Hill, from 1877–1878 until his death in 1895. Perched on a hilltop, the site offers a sweeping view of the U.S. Capitol and the Washington, D.C., skyline.

"Maryland, My Maryland" was the state song of the U.S. state of Maryland from 1939 until 2021. The song is set to the melody of "Lauriger Horatius" — the same tune "O Tannenbaum" was taken from. The lyrics are from a nine-stanza poem written by James Ryder Randall (1839–1908) in 1861. The state's general assembly adopted "Maryland, My Maryland" as the state song on April 29, 1939.

The Francis Parkman Prize, named after Francis Parkman, is awarded by the Society of American Historians for the best book in American history each year. Its purpose is to promote literary distinction in historical writing. The Society of American Historians is an affiliate of the American Historical Association.

The Heroic Slave, a Heartwarming Narrative of the Adventures of Madison Washington, in Pursuit of Liberty is a short piece of fiction, or novella, written by abolitionist Frederick Douglass, at the time a fugitive slave based in Boston. When the Rochester Ladies' Anti Slavery Society asked Douglass for a short story to go in their collection, Autographs for Freedom, Douglass responded with The Heroic Slave. The novella, published in 1852 by John P. Jewett and Company, was Douglass's first and only published work of fiction.

Margaretta Forten was an African-American suffragist and abolitionist.

Consensus history is a term used to define a style of American historiography and classify a group of historians who emphasize the basic unity of American values and the American national character and downplay conflicts, especially conflicts along class lines, as superficial and lacking in complexity. The term originated with historian John Higham, who coined it in a 1959 article in Commentary titled "The Cult of the American Consensus". Consensus history saw its primary period of influence in the 1950s, and it remained the dominant mode of American history until historians of the New Left began to challenge it in the 1960s.

"What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?" was a speech delivered by Frederick Douglass on July 5, 1852, at Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York, at a meeting organized by the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society. In the address, Douglass states that positive statements about perceived American values, such as liberty, citizenship, and freedom, were an offense to the enslaved population of the United States because they lacked those rights. Douglass referred not only to the captivity of enslaved people, but to the merciless exploitation and the cruelty and torture that slaves were subjected to in the United States.

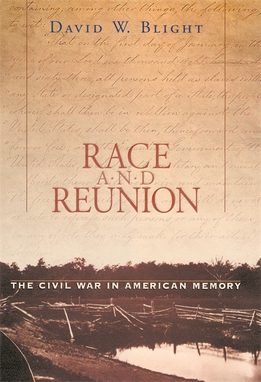

Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory is a 2001 book by the American historian David W. Blight. The book was awarded the Frederick Douglass Prize for the best book on slavery of 2001.

Lawrence Waldemar Tonner was an 1870 immigrant from Denmark who became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1875. Tonner met Jesse Shepard/Francis Grierson in 1885 and became his companion and personal secretary for more than 40 years, while they traveled and lived together in Europe and the United States. Tonner began his career as a translator in 1892 for the U.S. government in London, and was an aide and translator for Herbert Hoover after World War I. Tonner died in Los Angeles, California.

Kate Stone, was an American diarist and community leader. She was the daughter of a wealthy cotton farmer and slaveholder in the Southern United States. She is remembered in American history and literature for her diary, Brokenburn: The Journal of Kate Stone, 1861-1865, edited by John Q. Anderson, which she kept during the time of the American Civil War, printed in 1955, which she kept continuously from May 1861 to November 1865; shorter supplements date from 1867 and 1868. Stone died in 1907.