Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called theory of knowledge, it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowledge in the form of skills, and knowledge by acquaintance as a familiarity through experience. Epistemologists study the concepts of belief, truth, and justification to understand the nature of knowledge. To discover how knowledge arises, they investigate sources of justification, such as perception, introspection, memory, reason, and testimony.

Philosophy of religion is "the philosophical examination of the central themes and concepts involved in religious traditions". Philosophical discussions on such topics date from ancient times, and appear in the earliest known texts concerning philosophy. The field involves many other branches of philosophy, including metaphysics, epistemology, logic, ethics, aesthetics, philosophy of language, and philosophy of science.

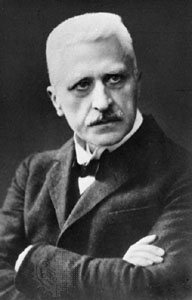

Thomas Reid was a religiously trained Scottish philosopher best known for his philosophical method, his theory of perception, and its wide implications on epistemology, and as the developer and defender of an agent-causal theory of free will. He also focused extensively on ethics, theory of action, language and philosophy of mind.

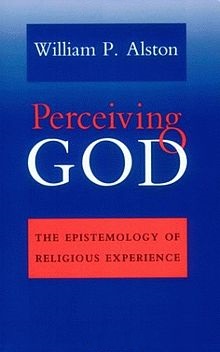

William Payne Alston was an American philosopher. He is widely considered to be one of the most important epistemologists and philosophers of religion of the twentieth century, and is also known for his work in metaphysics and the philosophy of language. His views on foundationalism, internalism and externalism, speech acts, and the epistemic value of mystical experience, among many other topics, have been very influential. He earned his PhD from the University of Chicago and taught at the University of Michigan, Rutgers University, University of Illinois, and Syracuse University.

Alvin Carl Plantinga is an American analytic philosopher who works primarily in the fields of philosophy of religion, epistemology, and logic.

Knowledge is an awareness of facts, a familiarity with individuals and situations, or a practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is often characterized as true belief that is distinct from opinion or guesswork by virtue of justification. While there is wide agreement among philosophers that propositional knowledge is a form of true belief, many controversies focus on justification. This includes questions like how to understand justification, whether it is needed at all, and whether something else besides it is needed. These controversies intensified in the latter half of the 20th century due to a series of thought experiments called Gettier cases that provoked alternative definitions.

Richard Granville Swinburne is an English philosopher. He is an Emeritus Professor of Philosophy at the University of Oxford. Over the last 50 years, Swinburne has been a proponent of philosophical arguments for the existence of God. His philosophical contributions are primarily in the philosophy of religion and philosophy of science. He aroused much discussion with his early work in the philosophy of religion, a trilogy of books consisting of The Coherence of Theism, The Existence of God, and Faith and Reason. He has been influential in reviving substance dualism as an option in philosophy of mind.

William Lane Craig is an American analytic philosopher, Christian apologist, author, and Wesleyan theologian who upholds the view of Molinism and neo-Apollinarianism. He is a professor of philosophy at Houston Christian University and at the Talbot School of Theology of Biola University.

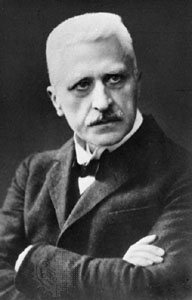

Rudolf Otto was a German Lutheran theologian, philosopher, and comparative religionist. He is regarded as one of the most influential scholars of religion in the early twentieth century and is best known for his concept of the numinous, a profound emotional experience he argued was at the heart of the world's religions. While his work started in the domain of liberal Christian theology, its main thrust was always apologetical, seeking to defend religion against naturalist critiques. Otto eventually came to conceive of his work as part of a science of religion, which was divided into the philosophy of religion, the history of religion, and the psychology of religion.

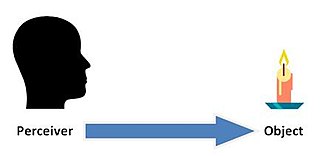

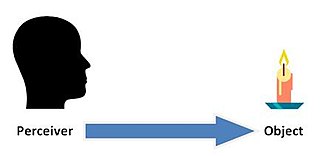

In philosophy of perception and epistemology, naïve realism is the idea that the senses provide us with direct awareness of objects as they really are. When referred to as direct realism, naïve realism is often contrasted with indirect realism.

The existence of God is a subject of debate in the philosophy of religion and theology. A wide variety of arguments for and against the existence of God can be categorized as logical, empirical, metaphysical, subjective or scientific. In philosophical terms, the question of the existence of God involves the disciplines of epistemology and ontology and the theory of value.

In the philosophy of religion, Reformed epistemology is a school of philosophical thought concerning the nature of knowledge (epistemology) as it applies to religious beliefs. The central proposition of Reformed epistemology is that beliefs can be justified by more than evidence alone, contrary to the positions of evidentialism, which argues that while non-evidential belief may be beneficial, it violates some epistemic duty. Central to Reformed epistemology is the proposition that belief in God may be "properly basic" and not need to be inferred from other truths to be rationally warranted. William Lane Craig describes Reformed epistemology as "One of the most significant developments in contemporary religious epistemology ... which directly assaults the evidentialist construal of rationality."

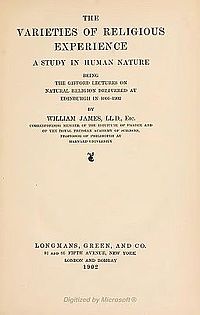

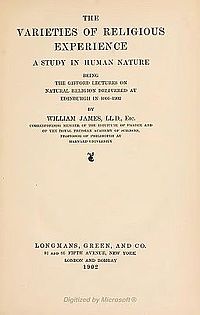

The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature is a book by Harvard University psychologist and philosopher William James. It comprises his edited Gifford Lectures on natural theology, which were delivered at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland between 1901 and 1902. The lectures concerned the psychological study of individual private religious experiences and mysticism, and used a range of examples to identify commonalities in religious experiences across traditions.

John Harwood Hick was an English-born philosopher of religion and theologian who taught in the United States for the larger part of his career. In philosophical theology, he made contributions in the areas of theodicy, eschatology, and Christology, and in the philosophy of religion he contributed to the areas of epistemology of religion and religious pluralism.

Scholarly approaches to mysticism include typologies of mysticism and the explanation of mystical states. Since the 19th century, mystical experience has evolved as a distinctive concept. It is closely related to mysticism but lays sole emphasis on the experiential aspect, be it spontaneous or induced by human behavior, whereas mysticism encompasses a broad range of practices aiming at a transformation of the person, not just inducing mystical experiences.

The argument from religious experience is an argument for the existence of God. It holds that the best explanation for religious experiences is that they constitute genuine experience or perception of a divine reality. Various reasons have been offered for and against accepting this contention.

R. William Hasker is an American philosopher and Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at Huntington University. For many years, he was editor of the prestigious journal Faith and Philosophy. He has published many journal articles and books dealing with issues such as the mind–body problem, theodicy, and divine omniscience.

Paul K. Moser is an American philosopher who writes on epistemology and the philosophy of religion. Moser is Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at Loyola University Chicago and a former editor of the American Philosophical Quarterly.

Religious epistemology broadly covers religious approaches to epistemological questions, or attempts to understand the epistemological issues that come from religious belief. The questions asked by epistemologists apply to religious beliefs and propositions whether they seem rational, justified, warranted, reasonable, based on evidence and so on. Religious views also influence epistemological theories, such as in the case of Reformed epistemology.

Scottish common sense realism, also known as the Scottish school of common sense, is a realist school of philosophy that originated in the ideas of Scottish philosophers Thomas Reid, Adam Ferguson, James Beattie, and Dugald Stewart during the 18th-century Scottish Enlightenment. Reid emphasized man's innate ability to perceive common ideas and that this process is inherent in and interdependent with judgement. Common sense, therefore, is the foundation of philosophical inquiry. Though best remembered for its opposition to the pervasive philosophy of David Hume, Scottish common sense philosophy is influential and evident in the works of Thomas Jefferson and late 18th-century American politics.