This article needs additional citations for verification .(March 2008) |

| Iranian art |

|---|

| Visual arts |

| Decorative arts |

| Literature |

| Performance arts |

| Other |

Iranian handicrafts are handicraft works originating from Iran.

This article needs additional citations for verification .(March 2008) |

| Iranian art |

|---|

| Visual arts |

| Decorative arts |

| Literature |

| Performance arts |

| Other |

Iranian handicrafts are handicraft works originating from Iran.

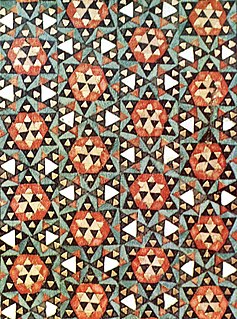

Termeh is a cloth that has been woven since the Safavid era in Iran. There is an argument between researchers about its origin. In the past, the first step in termeh weaving was preparing its raw materials. So it was very important to be careful while preparing wool, washing and drying it. Weaving termeh needs proper wool which has long fibres. Usually, the designs of Iranian termeh were the result of the co-operation between two main persons – an expert and a worker.[ citation needed ] Weaving termeh was a very careful, sensitive and time-consuming work that a good weaver could produce only 25 to 30 centimetres (1 feet) in a day.[ citation needed ] The background colours which are used in termeh are mostly jujube red, light red, green, orange and black. Termeh as a valuable textile has many different usages and patterns such as:

Termeh is a very durable cloth in which fixed colors are used so it can be washed and dried easily. Nowadays termeh is mostly used for a collectable tablecloth. These tablecloth are usually decorated with elaborate Persian embroidery called “sermeh doozy”.

Patteh is a wide piece of wool fabric that is needle worked with colored thread, mostly of silk. It is mostly created by women. [1]

Turquoise Inlaying both on jewelry and containers includes a copper, brass, silver, nickel or bronze object on parts of the surface of which small pieces of turquoise are set in mosaic fashion thus giving the object a special glamor. The production of Turquoise Inlaying includes two general stages:

A. Goldsmith Goldsmith includes the making and preparation of the object intended for Turquoise Inlaying using one of the metals indicated above. This is done by a goldsmith or forger using hands, press machine or both. After the object is formed generally, be it a piece of jewellery or a container, the part to be turquoise inlaid is demarked and a thin metal strand (of the same material as the metal used in the fabrication of the object) called “kandan” is placed around and soldered onto it. This part around the intended form is a so-called wall standing two or three millimeters above the surface of the container. This is usually done by or sometimes the turquoise inlayer himself. If the part prepared for Turquoise Inlaying takes up too much of the surface with an empty looking background, strands of the same metal are used to place smaller patterns of decorative nature (such as flowers, bushes, etc.) inside it and soldered again. This both makes the work more beautiful and makes the turquoise inlaid surface stronger.

B. Turquoise Inlaying First of all, the turquoise inlayer buys waste turquoise chips from turquoise forming workshops or turquoise mines in Mashhad, Neishabour or Damghan. Since such turquoise chips are usually accompanied by some earth and ordinary stone chips, they are first separated and cleaned. Then, the turquoise chips are graded based on their sizes so the right size turquoise chips are used in making each Turquoise Inlaying object in proportion to the surface area. In the next step, the object is heated (to about 30 °C) and, while heating, a “walnut lac” is sprinkled onto the parts that have to be turquoise laid so that the lac powder is almost melted and covers the intended surface. While the lac is still soft and sticky on the object surface, some of the turquoise chips that were prepared before based on their size are placed on the work surface. The chips must be placed in a way so that no space is left between them as far as possible. In order to fill the possible gaps between turquoise chips, the temperature is added (to about 40 °C) and some more lac powder is sprinkled onto the chips until the lac layer is softened to a melting form, and then try to fill all the spaces by adding smaller turquoise chips, or, as they say, the chips sit well on the surface. This is usually done by pressing the turquoise chips by hand onto the surface so that they stick fast to it. After the object is cooled, the lac covered parts become rigid. After that stage, the parts covered by lac and turquoise chips are polished with emery so the extra lac and little raised parts of the chips are flattened. That is the stage where the colour of the turquoise chips becomes visible as turquoise and that of lac as black (or dark brown) in the spaces between the chips. After this stage is completed, if there is still some fallouts in some parts of the work, the object is heated again, and the empty parts are restored with small turquoise chips and lac. Then, the surface is polished and honed again. The restoration is sometimes done with a type of turquoise colored putty that is prepared with “mol” mud, oil and lapis paint. The final stage of Turquoise Inlaying is burnishing which is done in two stages itself. The first stage consists of burnishing the metal parts which is done at a goldsmith or machining workshop where the opaque layer that is formed on the metal parts during Turquoise Inlaying is removed with hand tools or a machine blade, and then, those parts are polished so the metal becomes shiny. The second stage consists of burnishing the turquoise inlaid product. After polishing the metal parts of the object, the work is returned to the turquoise inlayer’s workshop where the turquoise inlaid surface is polished with olive or sesame oil so that part becomes shiny, too. A Turquois Inlaying craftsman employs different tools and devices for different stages of the job mostly including dies, hammers, drills, natural gas and gasoline torches, pincers, pliers, forceps, different metal pipes tweezers, files and emeries. The most important point in Turquoise Inlaying is the correct installation of turquoise chips on the metal so that it is strong enough and the chips do not come off while burnishing the work. The other important point is that a piece of turquoise inlaid work will be of more artistic value if the turquoise chips are installed more regularly in close contact, i.e. without a space in between.

Turquoise is an opaque, blue-to-green mineral that is a hydrated phosphate of copper and aluminium, with the chemical formula CuAl6(PO4)4(OH)8·4H2O. It is rare and valuable in finer grades and has been prized as a gemstone and ornamental stone for thousands of years owing to its unique hue. Like most other opaque gems, turquoise has been devalued by the introduction of treatments, imitations and synthetics into the market. The robin’s egg blue or sky blue color of the Persian turquoise mined near the modern city of Neyshabur in Iran has been used as a guiding reference for evaluating turquoise quality.

Marquetry is the art and craft of applying pieces of veneer to a structure to form decorative patterns, designs or pictures. The technique may be applied to case furniture or even seat furniture, to decorative small objects with smooth, veneerable surfaces or to freestanding pictorial panels appreciated in their own right.

Zari is an even thread traditionally made of fine gold or silver used in traditional Indian, Bangladeshi and Pakistani garments, especially as brocade in saris etc. This thread is woven into fabrics, primarily of silk, to make intricate patterns and elaborate designs of embroidery called zardozi. Zari was popularised during the Moghul era, the port of Surat was linked to the Meccan pilgrimage route which served as a major factor for re-introducing this ancient craft in India. During the Vedic ages, the gold embroidery was associated with the grandeur and regal attire of gods, kings, and literary figures (gurus){as shown in the movies}.

The arts of Iran are one of the richest art heritages in world history and encompasses many traditional disciplines including architecture, painting, literature, music, weaving, pottery, calligraphy, metalworking and stonemasonry. There is also a very vibrant Iranian modern and contemporary art scene, as well as cinema and photography. For a history of Persian visual art up to the early 20th century, see Persian art, and also Iranian architecture.

Paithani is a variety of sari, named after the Paithan town in Aurangabad district from state of Maharashtra in India where the sari was first made by hand. Present day Yeola town in Nashik, Maharashtra is the largest manufacturer of Paithani.

A Banarasi sari is a sari made in Varanasi, an ancient city which is also called Benares (Banaras). The saris are among the finest saris in India and are known for their gold and silver brocade or zari, fine silk and opulent embroidery. The saris are made of finely woven silk and are decorated with intricate design, and, because of these engravings, are relatively heavy.

Embroidery in India includes dozens of embroidery styles that vary by region and clothing styles. Designs in Indian embroidery are formed on the basis of the texture and the design of the fabric and the stitch. The dot and the alternate dot, the circle, the square, the triangle, and permutations and combinations of these constitute the design.

Khātam is an ancient Persian technique of inlaying. It is a version of marquetry where art forms are made by decorating the surface of wooden articles with delicate pieces of wood, bone and metal precisely-cut intricate geometric patterns. Khatam-kari (خاتمکاری) or khatam-bandi (خاتمبندی) refers to the art of crafting a khatam. Common materials used in the construction of inlaid articles are gold, silver, brass, aluminum and twisted wire.

Silk in the Indian subcontinent is a luxury good. In India, about 97% of the raw mulberry silk is produced in the Indian states of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal. Mysore and North Bangalore, the upcoming site of a US$20 million "Silk City", contribute to a majority of silk production. Another emerging silk producer is Tamil Nadu where mulberry cultivation is concentrated in Salem, Erode and Dharmapuri districts. Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh and Gobichettipalayam, Tamil Nadu were the first locations to have automated silk reeling units.

The manufacture of textiles is one of the oldest of human technologies. To make textiles, the first requirement is a source of fiber from which a yarn can be made, primarily by spinning. The yarn is processed by knitting or weaving, which turns yarn into cloth. The machine used for weaving is the loom. For decoration, the process of colouring yarn or the finished material is dyeing. For more information of the various steps, see textile manufacturing.

Brocade is a class of richly decorative shuttle-woven fabrics, often made in colored silks and sometimes with gold and silver threads. The name, related to the same root as the word "broccoli", comes from Italian broccato meaning "embossed cloth", originally past participle of the verb broccare "to stud, set with nails", from brocco, "small nail", from Latin broccus, "projecting, pointed".

Bidriware is a metal handicraft from Bidar. It was developed in the 14th century C.E. during the rule of the Bahmani Sultans. The term "bidriware" originates from the township of Bidar, which is still the chief centre for the manufacture of the unique metalware. Due to its striking inlay artwork, bidriware is an important export handicraft of India and is prized as a symbol of wealth. The metal used is a blackened alloy of zinc and copper inlaid with thin sheets of pure silver. This native art form has obtained Geographical Indications (GI) registry.

Inlay covers a range of techniques in sculpture and the decorative arts for inserting pieces of contrasting, often coloured materials into depressions in a base object to form ornament or pictures that normally are flush with the matrix. A great range of materials have been used both for the base or matrix and for the inlays inserted into it. Inlay is commonly used in the production of decorative furniture, where pieces of coloured wood, precious metals or even diamonds are inserted into the surface of the carcass using various matrices including clearcoats and varnishes. Lutherie inlays are frequently used as decoration and marking on musical instruments, particularly the smaller strings.

Woodblock printing on textiles is the process of printing patterns on textiles, usually of linen, cotton or silk, by means of incised wooden blocks. It is the earliest and slowest of all methods of textile printing. Block printing by hand is a slow process. It is however, capable of yielding highly artistic results, some of which are unobtainable by any other method.

Goryeo ware refers to all types of Korean pottery and porcelain produced during the Goryeo dynasty, from 918 to 1392, but most often refers to celadon (greenware).

Gota patti or gota work is a type of Indian embroidery that originated in Rajasthan, India. It uses the applique technique. Small pieces of zari ribbon are applied onto the fabric with the edges sewn down to create elaborate patterns. Gota embroidery is used extensively in South Asian wedding and formal clothes.

Amuzgo textiles are those created by the Amuzgo indigenous people who live in the Mexican states of Guerrero and Oaxaca. The history of this craft extends to the pre-Columbian period, which much preserved, as many Amuzgos, especially in Xochistlahuaca, still wear traditional clothing. However, the introduction of cheap commercial cloth has put the craft in danger as hand woven cloth with elaborate designs cannot compete as material for regular clothing. Since the 20th century, the Amuzgo weavers have mostly made cloth for family use, but they have also been developing specialty markets, such as to collectors and tourists for their product.

Sermeh embroidery is an Iranian style of embroidery. Its origin dates back to the Achaemenid dynasty. It reached its zenith in the Safavid Dynasty. In this style of embroidery, gold and silver threads would be used to make decorating patterns on the surface of fabric; however, nowadays, almost entirely, threads twisted out of cheaper metals and alloys and metal like yarns have replaced gold and silver. The yarn used in patterning is springlike and elastic. Sermeh embroidery is the most popular in the cities of Isfahan, Yazd, Kashan.

The boteh, is an almond or pine cone-shaped motif in ornament with a sharp-curved upper end. Though of Persian origin, it is very common in India, Azerbaijan, Turkey and other countries of the Near East. Via Kashmir shawls it spread to Europe, where patterns using it are known as paisleys, as Paisley, Renfrewshire in Scotland was a major centre making them.

Persian art or Iranian art has one of the richest art heritages in world history and has been strong in many media including architecture, painting, weaving, pottery, calligraphy, metalworking and sculpture. At different times, influences from the art of neighbouring civilizations have been very important, and latterly Persian art gave and received major influences as part of the wider styles of Islamic art. This article covers the art of Persia up to 1925, and the end of the Qajar dynasty; for later art see Iranian modern and contemporary art, and for traditional crafts see arts of Iran. Rock art in Iran is its most ancient surviving art. Iranian architecture is covered at that article.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Handicrafts of Iran . |