Related Research Articles

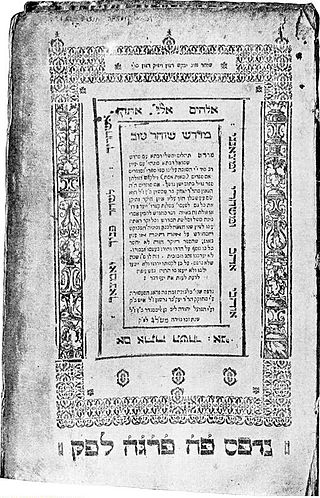

Midrash is expansive Jewish Biblical exegesis using a rabbinic mode of interpretation prominent in the Talmud. The word itself means "textual interpretation", "study", or "exegesis", derived from the root verb darash (דָּרַשׁ), which means "resort to, seek, seek with care, enquire, require".

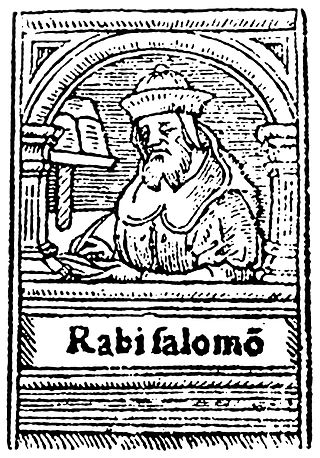

Shlomo Yitzchaki, commonly known by the acronym Rashi, was a French rabbi who authored comprehensive commentaries on the Talmud and Hebrew Bible.

Rabbinic literature, in its broadest sense, is the entire spectrum of works authored by rabbis throughout Jewish history. The term typically refers to literature from the Talmudic era, as opposed to medieval and modern rabbinic writings. It aligns with the Hebrew term Sifrut Chazal, which translates to “literature [of our] sages” and generally pertains only to the sages (Chazal) from the Talmudic period. This more specific sense of "Rabbinic literature"—referring to the Talmud, Midrashim, and related writings, but hardly ever to later texts—is how the term is generally intended when used in contemporary academic writing. The terms mefareshim and parshanim almost always refer to later, post-Talmudic writers of rabbinic glosses on Biblical and Talmudic texts.

Torah study is the study of the Torah, Hebrew Bible, Talmud, responsa, rabbinic literature, and similar works, all of which are Judaism's religious texts. According to Rabbinic Judaism, the study is done for the purpose of the mitzvah ("commandment") of Torah study itself.

ArtScroll is an imprint of translations, books and commentaries from an Orthodox Jewish perspective published by Mesorah Publications, Ltd., a publishing company based in Rahway, New Jersey. Rabbi Nosson Scherman is the general editor.

Exegesis is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Biblical works. In modern usage, exegesis can involve critical interpretations of virtually any text, including not just religious texts but also philosophy, literature, or virtually any other genre of writing. The phrase Biblical exegesis can be used to distinguish studies of the Bible from other critical textual explanations.

David Weiss Halivni was a European-born American-Israeli rabbi, scholar in the domain of Jewish sciences, and Professor of Talmud. He served as Reish Metivta of the Union for Traditional Judaism's rabbinical school.

Jacob ben Meir, best known as Rabbeinu Tam, was one of the most renowned Ashkenazi Jewish rabbis and leading French Tosafists, a leading halakhic authority in his generation, and a grandson of Rashi. Known as "Rabbeinu", he acquired the Hebrew suffix "Tam" meaning straightforward; it was originally used in the Book of Genesis to describe his biblical namesake, Jacob.

David Kimhi (1160–1235), also known by the Hebrew acronym as the RaDaK (רַדָּ״ק), was a medieval rabbi, biblical commentator, philosopher, and grammarian.

Aggadah is the non-legalistic exegesis which appears in the classical rabbinic literature of Judaism, particularly the Talmud and Midrash. In general, Aggadah is a compendium of rabbinic texts that incorporates folklore, historical anecdotes, moral exhortations, and practical advice in various spheres, from business to medicine.

Samuel ben Meir, after his death known as the "Rashbam", a Hebrew acronym for RAbbi SHmuel Ben Meir, was a leading French Tosafist and grandson of Shlomo Yitzhaki, "Rashi".

Joseph Qimḥi or Kimchi (1105–1170) was a medieval Jewish rabbi and biblical commentator. He was the father of Moses and David Kimhi, and the teacher of Rabbi Menachem Ben Simeon and poet Joseph Zabara.

Savora is a term used in Jewish law and history to signify one among the leading rabbis living from the end of period of the Amoraim to the beginning of the Geonim. As a group they are also referred to as the Rabbeinu Sevorai or Rabanan Saborai, and may have played a large role in giving the Talmud its current structure. Modern scholars also use the plural term Stammaim for the authors of unattributed statements in the Gemara.

Pardes is a Kabbalistic theory of Biblical exegesis first advanced by Moses de León, adapting the popular "fourfold" method of medieval Christianity. The term, sometimes also rendered PaRDeS, means "orchard" when taken literally, but is used in this context as a Hebrew acronym formed from the initials of the following four approaches:

Joseph ben Isaac Bekhor Shor of Orléans was a French tosafist, exegete, and poet who flourished in the second half of the 12th century. He was the father of Abraham ben Joseph of Orleans and Saadia Bekhor Shor.

Soncino Press is a Jewish publishing company based in the United Kingdom that has published a variety of books of Jewish interest, most notably English translations and commentaries to the Talmud and Hebrew Bible. The Soncino Hebrew Bible and Talmud translations and commentaries were widely used in both Orthodox and Conservative synagogues until the advent of other translations beginning in the 1990s.

Jewish commentaries on the Bible are biblical commentaries of the Hebrew Bible from a Jewish perspective. Translations into Aramaic and English, and some universally accepted Jewish commentaries with notes on their method of approach and also some modern translations into English with notes are listed.

Shnayim mikra ve-echad targum, is the Jewish practice of reading the weekly Torah portion in a prescribed manner. In addition to hearing the Torah portion read in the synagogue, a person should read it himself twice during that week, together with a translation usually by Targum Onkelos and/or Rashi's commentary. In addition, while not required by law, there exists an Ashkenazi custom to also read the portion from the Prophets with its targum.

Sifrei Kodesh, commonly referred to as sefarim, or in its singular form, sefer, are books of Jewish religious literature and are viewed by religious Jews as sacred. These are generally works of Torah literature, i.e. Tanakh and all works that expound on it, including the Mishnah, Midrash, Talmud, and all works of Musar, Hasidism, Kabbalah, or machshavah. Historically, sifrei kodesh were generally written in Hebrew with some in Judeo-Aramaic or Arabic, although in recent years, thousands of titles in other languages, most notably English, were published. An alternative spelling for 'sefarim' is seforim.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Judaism:

References

- 1 2 Goldin, S. (2007). Unlocking the Torah Text: Bereishit. Gefen Publishing. ISBN 978-965-229-412-8

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rabinowitz, Louis. "The Talmudic Meaning of Peshat." Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Thought 6.1 (1963). Web.

- 1 2 3 4 Garfinkel, Stephen. "Clearing Peshat and Derash." Hebrew Bible/Old Testament - The History of Its Interpretation. Comp. Chris Brekelmans and Menahem Haran. Ed. Magne Sæbø. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2000. 130-34. Print.

- ↑ "PESHAṬ - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rabinowitz, Louis Isaac (2007). "Peshat". In Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica . Vol. 16 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. p. 8-9. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4 – via Gale Virtual Reference Library. Available online.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sarah Kamin, Rashi: Peshuto shel mikra umidrasho shel mikra (2000), p.23-56

- ↑ Angel, Rabbi Hayyim. "From Black Fire to White Fire: Conversations about Religious Tanakh Methodology." The Institute for Jewish Ideas and Ideals. 4 Sept. 2008. Web.

- ↑ Talmud, Shabbat 63a

- ↑ Talmud, Yevamot 11b

- ↑ Talmud, Yevamot 24a

- 1 2 3 4 Lockshin, Martin I. "Lonely Man of Peshat." Jewish Quarterly Review 99.2 (2009): 291-300. Print.

- 1 2 Berger, Yitzhak. "The Contextual Exegesis of Rabbi Eliezer of Beaugency and the Climax of the Northern French Peshat Tradition." Jewish Studies Quarterly 15.2 (2008): 115-29. Print.

- 1 2 3 4 Berger, Yitzhak. "Peshat and the Authority of Ḥazal in the Commentaries of Radak." Association for Jewish Studies Review 31.1 (2007): 41-59. Print.

- ↑ Commentary attributed to a student of Saadiah Gaon, Chronicles 36:13. Hebrew וזה לך האות שתדע לשון המפרשים איזה מפרש בטוב ואיזה מפרש שלא בטוב: כל פרשן שמפרש תחלה פשוטו של מקרא בקצור לשון ואח"כ מביא קצת מדרש רבותינו זה פתרון טוב, וחלופיהן בגולם.