Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky, sometimes transliterated as Dostoyevsky, was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. Numerous literary critics regard him as one of the greatest novelists in all of world literature, as many of his works are considered highly influential masterpieces.

The House of the Dead is a semi-autobiographical novel published in 1860–2 in the journal Vremya by Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky. It has also been published in English under the titles Notes from the House of the Dead, Memoirs from the House of the Dead and Notes from a Dead House, which are more literal translations of the Russian title. The novel portrays the life of convicts in a Siberian prison camp. It is generally considered to be a fictionalised memoir; a loosely-knit collection of experiences, events and philosophical discussion based on Dostoevsky's experiences as a prisoner, organised around theme and character rather than plot. Dostoevsky spent four years in a forced-labour prison camp in Siberia following his conviction for involvement in the Petrashevsky Circle. This experience allowed him to describe with great authenticity the conditions of prison life and the characters of the convicts.

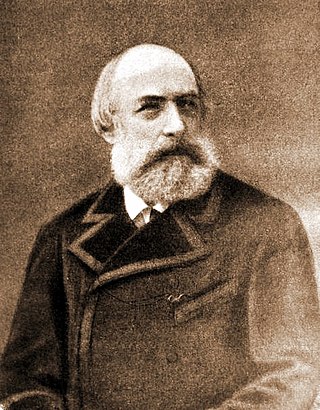

Vissarion Grigoryevich Belinsky was a Russian literary critic of Westernizing tendency. Belinsky played one of the key roles in the career of poet and publisher Nikolay Nekrasov and his popular magazine Sovremennik. He was the most influential of the Westernizers, especially among the younger generation. He worked primarily as a literary critic, because that area was less heavily censored than political pamphlets. He agreed with Slavophiles that society had precedence over individualism, but he insisted the society had to allow the expression of individual ideas and rights. He strongly opposed Slavophiles on the role of Orthodoxy, which he considered a retrograde force. He emphasized reason and knowledge, and attacked autocracy and theocracy.

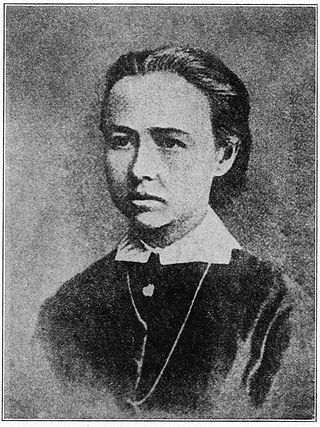

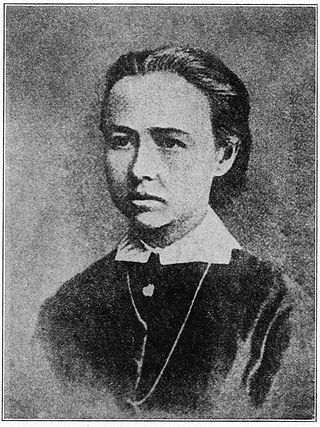

Sophia Lvovna Perovskaya was a Russian revolutionary and a member of the revolutionary organization Narodnaya Volya. She helped orchestrate the assassination of Alexander II of Russia, for which she was executed by hanging.

Sergey Gennadiyevich Nechayev was a Russian anarchist, part of the Russian nihilist movement, known for his single-minded pursuit of revolution by any means necessary, including revolutionary terror.

The Russian nihilist movement was a philosophical, cultural, and revolutionary movement in the Russian Empire during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, from which the broader philosophy of nihilism originated. In Russian, the word nigilizm came to represent the movement's unremitting attacks on morality, religion, and traditional society. Even as it was yet unnamed, the movement arose from a generation of young radicals disillusioned with the social reformers of the past, and from a growing divide between the old aristocratic intellectuals and the new radical intelligentsia.

Apollon Nikolayevich Maykov was a Russian poet, best known for his lyric verse showcasing images of Russian villages, nature, and history. His love for ancient Greece and Rome, which he studied for much of his life, is also reflected in his works. Maykov spent four years translating the epic The Tale of Igor's Campaign (1870) into modern Russian. He translated the folklore of Belarus, Greece, Serbia and Spain, as well as works by Heine, Adam Mickiewicz and Goethe, among others. Several of Maykov's poems were set to music by Russian composers, among them Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky.

Aleksey Nikolayevich Pleshcheyev was a radical Russian poet of the 19th century, once a member of the Petrashevsky Circle.

Apollon Aleksandrovich Grigoryev was a Russian poet, literary and theatrical critic, translator, memoirist and author of popular art songs.

Mikhail Vasilyevich Butashevich-Petrashevsky, commonly known as Mikhail Petrashevsky, was a Russian revolutionary and Utopian theorist.

Netochka Nezvanova is an unfinished novel by Fyodor Dostoevsky. It was originally intended as a large scale work in the form of a 'confession', but a background sketch of the eponymous heroine's childhood and adolescence is all that was completed and published. According to translator Jane Kentish, this first publication was intended as "no more than a prologue to the novel". Dostoevsky began work on the novel in 1848 and the first completed section was published at the end of 1849. Further work was prevented by the author's arrest and exile to a Siberian detention camp for his part in the activities of the Petrashevsky Circle. After his return in 1859, Dostoevsky never resumed work on Netochka Nezvanova, leaving this fragment forever incomplete.

Mikhail Mikhailovich Dostoevsky was a Russian short story writer, publisher, literary critic and the elder brother of Fyodor Dostoevsky. They were less than a year apart in age and spent their childhood together.

Valerian Nikolayevich Maykov was a Russian writer and literary critic, son of painter Nikolay Maykov, brother of poet Apollon and novelist Vladimir Maykov. Valerian Maykov, once a Petrashevsky Circle associate, was considered by contemporaries as heir to Vissarion Belinsky's position of Russia's leading critic, and later credited for being arguably the first in Russia to introduce scientific approach to the art of literary criticism.

Poor Folk, sometimes translated as Poor People, is the first novel by Fyodor Dostoevsky, written over the span of nine months between 1844 and 1845. Dostoevsky was in financial difficulty because of his extravagant lifestyle and his developing gambling addiction; although he had produced some translations of foreign novels, they had little success, and he decided to write a novel of his own to try to raise funds.

The Landlady is a novella by Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky, written in 1847. Set in Saint Petersburg, it tells of an abstracted young man, Vasily Mikhailovich Ordynov, and his obsessive love for Katerina, the wife of a dismal husband whom Ordynov perceives as a malignant fortune-teller or mystic. The story has echoes of Russian folklore and may contain autobiographical references. In its time The Landlady had a mixed reception, more recently being seen as perhaps unique in Dostoevsky's oeuvre. The first part of the novella was published in October 1847 in Notes of the Fatherland, the second part in November that year.

Two Fates is a poem by Apollon Maykov, first published in 1845 in Saint Petersburg, as a separate edition, under the title "Two Fates. A Real Story by A.N.Maykov" and with considerable censorship cuts. It hasn't been re-issued in the author's lifetime and first appeared in its original form in The Selected Works by A.N.Maykov.

Sergey Fyodorovich Durov was a Russian poet, translator, writer, and political activist. A member of the Petrashevsky Circle and later the leader of his own underground group of intellectuals, Durov was arrested in 1849 and spent 8 months in the Petropavloskaya Fortress, followed by 4 years in Omsk prison.

Alexander Ivanovich Palm was a Russian poet, novelist and playwright, who also used the pseudonym P. Alminsky. A member of the Petrashevsky Circle, Palm in 1847 was arrested, spent 8 months in the Petropavlovsk Fortress, had his death sentence changed to deportation and served 7 years in the Russian Army. Among his best known works are Alexey Slobodin. The History of One Family and Our Friend Neklyuzhev.

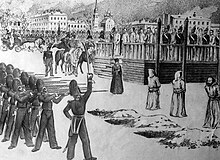

Nikolay Alexandrovich Speshnev was a 19th-century Russian aristocrat and political activist, best known for his involvement with the pro-socialist literary discussion group the Petrashevsky Circle. He formed a secret revolutionary society from among the members of the circle, which included the young Fyodor Dostoevsky. After the government of Tsar Nicholas I arrested the members of the Petrashevsky Circle in 1849, Speshnev was interrogated, threatened with torture, and eventually sentenced, along with Dostoevsky, Petrashevsky and others, to execution by firing squad. The sentence was commuted to hard labour in Siberia, but the prisoners were only informed of this after enduring a mock execution.

Stepan Dmitrievich Yanovsky was a family doctor of Fyodor Dostoyevsky. He watched after the writer's health from 1846 to 1849. He was also an author of memoirs about Dostoevsky. Some features of Yanovsky and some family events from his life were reflected in the image of Dostoevsky's character Pavel Pavlovich Trusotsky.