Related Research Articles

Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl was an Austrian-German philosopher and mathematician who established the school of phenomenology.

Maurice Jean Jacques Merleau-Ponty was a French phenomenological philosopher, strongly influenced by Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. The constitution of meaning in human experience was his main interest and he wrote on perception, art, politics, religion, biology, psychology, psychoanalysis, language, nature, and history. He was the lead editor of Les Temps modernes, the leftist magazine he established with Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir in 1945.

Hermeneutics is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts. As necessary, hermeneutics may include the art of understanding and communication.

Phenomenology is the philosophical study of objectivity and, more generally, reality as subjectively lived and experienced. It seeks to investigate the universal features of consciousness while avoiding assumptions about the external world, aiming to describe phenomena as they appear to the subject, and to explore the meaning and significance of the lived experiences.

Franz Clemens Honoratus Hermann Josef Brentano was a German philosopher and psychologist. His 1874 Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint, considered his magnum opus, is credited with having reintroduced the medieval scholastic concept of intentionality into contemporary philosophy.

Alfred Schutz was an Austrian philosopher and social phenomenologist whose work bridged sociological and phenomenological traditions. Schutz is gradually being recognized as one of the 20th century's leading philosophers of social science. He related Edmund Husserl's work to the social sciences, using it to develop the philosophical foundations of Max Weber's sociology, in his major work Phenomenology of the Social World. However, much of his influence arose from the publication of his Collected Papers in the 1960s.

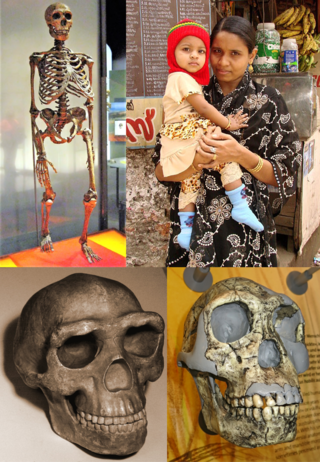

Homo is a genus of Hominidae that emerged from the genus Australopithecus and encompasses the extant species Homo sapiens and a number of extinct species classified as either ancestral or closely related to modern humans. These include Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis. The oldest member of the genus is Homo habilis, with records of just over 2 million years ago. Homo, together with the genus Paranthropus, is probably most closely related to the species Australopithecus africanus within Australopithecus. The closest living relatives of Homo are of the genus Pan, with the ancestors of Pan and Homo estimated to have diverged around 5.7-11 million years ago during the Late Miocene.

Neurophenomenology refers to a scientific research program aimed to address the hard problem of consciousness in a pragmatic way. It combines neuroscience with phenomenology in order to study experience, mind, and consciousness with an emphasis on the embodied condition of the human mind. The field is very much linked to fields such as neuropsychology, neuroanthropology and behavioral neuroscience and the study of phenomenology in psychology.

The phenomenology of religion concerns the experiential aspect of religion, describing religious phenomena in terms consistent with the orientation of worshippers. It views religion as made up of different components, and studies these components across religious traditions in order to gain some understanding of them.

Phenomenology may refer to:

Human taxonomy is the classification of the human species within zoological taxonomy. The systematic genus, Homo, is designed to include both anatomically modern humans and extinct varieties of archaic humans. Current humans have been designated as subspecies Homo sapiens sapiens, differentiated, according to some, from the direct ancestor, Homo sapiens idaltu.

Human science studies the philosophical, biological, social, justice, and cultural aspects of human life. Human science aims to expand the understanding of the human world through a broad interdisciplinary approach. It encompasses a wide range of fields - including history, philosophy, sociology, psychology, justice studies, evolutionary biology, biochemistry, neurosciences, folkloristics, and anthropology. It is the study and interpretation of the experiences, activities, constructs, and artifacts associated with human beings. The study of human sciences attempts to expand and enlighten the human being's knowledge of its existence, its interrelationship with other species and systems, and the development of artifacts to perpetuate the human expression and thought. It is the study of human phenomena. The study of the human experience is historical and current in nature. It requires the evaluation and interpretation of the historic human experience and the analysis of current human activity to gain an understanding of human phenomena and to project the outlines of human evolution. Human science is an objective, informed critique of human existence and how it relates to reality.Underlying human science is the relationship between various humanistic modes of inquiry within fields such as history, sociology, folkloristics, anthropology, and economics and advances in such things as genetics, evolutionary biology, and the social sciences for the purpose of understanding our lives in a rapidly changing world. Its use of an empirical methodology that encompasses psychological experience in contrasts with the purely positivistic approach typical of the natural sciences which exceeds all methods not based solely on sensory observations. Modern approaches in the human sciences integrate an understanding of human structure, function on and adaptation with a broader exploration of what it means to be human. The term is also used to distinguish not only the content of a field of study from that of the natural science, but also its methodology.

Phenomenology or phenomenological psychology, a sub-discipline of psychology, is the scientific study of subjective experiences. It is an approach to psychological subject matter that attempts to explain experiences from the point of view of the subject via the analysis of their written or spoken words. The approach has its roots in the phenomenological philosophical work of Edmund Husserl.

Bracketing means looking at a situation and refraining from judgement and biased opinions to wholly understand an experience. The preliminary step in the philosophical movement of phenomenology is describing an act of suspending judgment about the natural world to instead focus on analysis of experience. Suspending judgement involves stripping away every connotation and assumption made about an object. Its earliest conception can be traced back to Immanuel Kant who argued that the only reality that one can know is the one each individual experiences in their mind. Edmund Husserl, building on Kant’s ideas, first proposed bracketing in 1913, to help better understand another’s phenomena.

The word noema derives from the Greek word νόημα meaning "mental object". The philosopher Edmund Husserl used noema as a technical term in phenomenology to stand for the object or content of a thought, judgement, or perception, but its precise meaning in his work has remained a matter of controversy.

Phenomenology within sociology, or phenomenological sociology, examines the concept of social reality as a product of intersubjectivity. Phenomenology analyses social reality in order to explain the formation and nature of social institutions. The application of phenomenological ideas in sociology differs from other social science applications of social science applications.

Phenomenological description is a method of phenomenology that attempts to depict the structure of first person lived experience, rather than theoretically explain it. This method was first conceived of by Edmund Husserl. It was developed through the latter work of Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, Emmanuel Levinas and Maurice Merleau-Ponty — and others. It has also been developed with recent strands of modern psychology and cognitive science.

The Logical Investigations is a two-volume work by the philosopher Edmund Husserl, in which the author discusses the philosophy of logic and criticizes psychologism, the view that logic is based on psychology.

Buddhist thought and Western philosophy include several parallels.

The diet of known human ancestors varies dramatically over time. Strictly speaking, according to evolutionary anthropologists and archaeologists, there is not a single hominin Paleolithic diet. The Paleolithic covers roughly 2.8 million years, concurrent with the Pleistocene, and includes multiple human ancestors with their own evolutionary and technological adaptations living in a wide variety of environments. This fact with the difficulty of finding conclusive evidence often makes broad generalizations of the earlier human diets very difficult. Humans' pre-hominin primate ancestors were broadly herbivorous, relying on either foliage or fruits and nuts and the shift in dietary breadth during the Paleolithic is often considered a critical point in hominin evolution. A generalization between Paleolithic diets of the various human ancestors that many anthropologists do make is that they are all to one degree or another omnivorous and are inextricably linked with tool use and new technologies.

References

- ↑ OED, 3rd ed.

- ↑ Hu et al., 2023

- ↑ in observation

- ↑ how to observe

- ↑ Davidsen 2011.

- ↑ Seamon 2018.

- ↑ Cilesiz 2011.

- ↑ "Phe-nom-e-non | Search Online Etymology Dictionary".

- ↑ OED, 3rd ed.