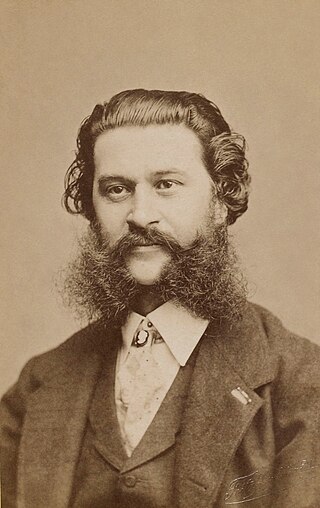

Jacques Offenbach 20 June 1819 – 5 October 1880) was a German-born French composer, cellist and impresario. He is remembered for his nearly 100 operettas of the 1850s to the 1870s, and his uncompleted opera The Tales of Hoffmann. He was a powerful influence on later composers of the operetta genre, particularly Franz von Suppé, Johann Strauss Jr. and Arthur Sullivan. His best-known works were continually revived during the 20th century, and many of his operettas continue to be staged in the 21st. The Tales of Hoffmann remains part of the standard opera repertory.

Richard Georg Strauss was a German composer and conductor best known for his tone poems and operas. Considered a leading composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras, he has been described as a successor of Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt. Along with Gustav Mahler, he represents the late flowering of German Romanticism, in which pioneering subtleties of orchestration are combined with an advanced harmonic style.

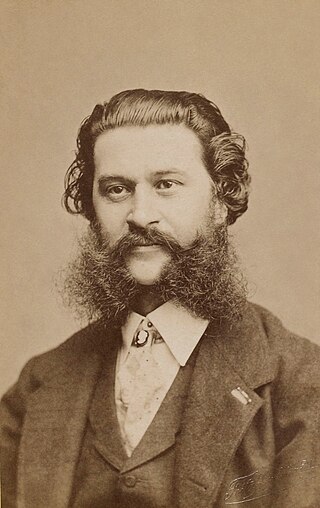

Johann Baptist Strauss II, also known as Johann Strauss Jr., the Younger or the Son, was an Austrian composer of light music, particularly dance music and operettas as well as a violinist. He composed over 500 waltzes, polkas, quadrilles, and other types of dance music, as well as several operettas and a ballet. In his lifetime, he was known as "The Waltz King", and was largely responsible for the popularity of the waltz in Vienna during the 19th century. Some of Johann Strauss's most famous works include "The Blue Danube", "Kaiser-Walzer", "Tales from the Vienna Woods", "Frühlingsstimmen", and the "Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka". Among his operettas, Die Fledermaus and Der Zigeunerbaron are the best known.

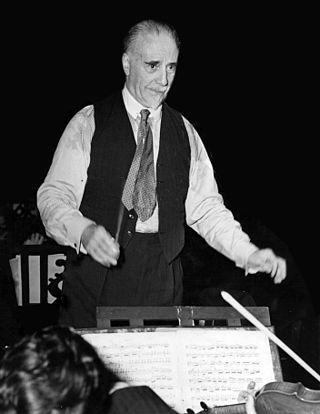

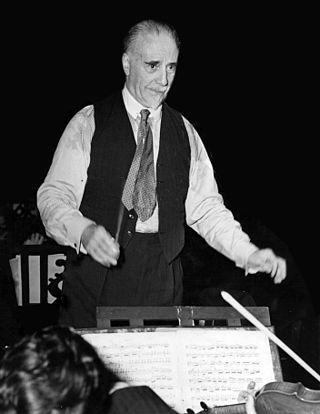

Sir Thomas Beecham, 2nd Baronet, CH was an English conductor and impresario best known for his association with the London Philharmonic and the Royal Philharmonic orchestras. He was also closely associated with the Liverpool Philharmonic and Hallé orchestras. From the early 20th century until his death, Beecham was a major influence on the musical life of Britain and, according to the BBC, was Britain's first international conductor.

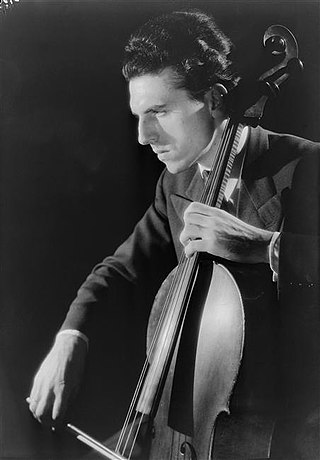

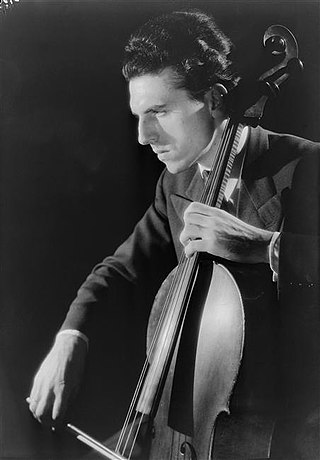

Paul Tortelier was a French cellist and composer. After an outstanding student career at the Conservatoire de Paris he played in orchestras in France and the US before the Second World War. After the war he became a well-known soloist, playing in countries round the globe. He taught at conservatoires in France, Germany and China, and gave televised masterclasses in England. He was particularly associated with the solo part in Richard Strauss's Don Quixote, cello concertos by Elgar and others, and Bach's Cello Suites.

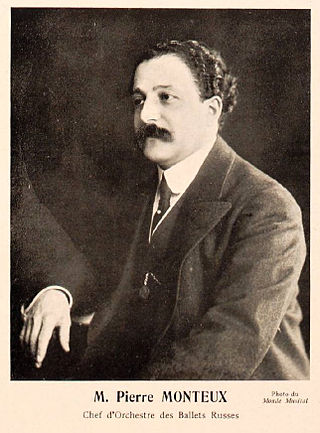

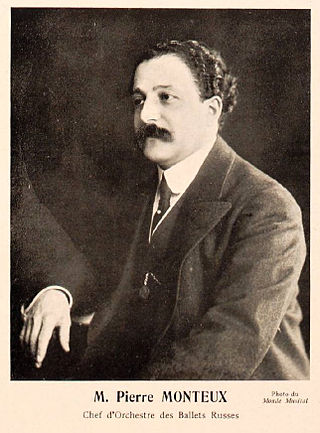

Pierre Benjamin Monteux was a French conductor. After violin and viola studies, and a decade as an orchestral player and occasional conductor, he began to receive regular conducting engagements in 1907. He came to prominence when, for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes company between 1911 and 1914, he conducted the world premieres of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring and other prominent works including Petrushka, The Nightingale, Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé, and Debussy's Jeux. Thereafter he directed orchestras around the world for more than half a century.

Sir Henry Joseph Wood was an English conductor best known for his association with London's annual series of promenade concerts, known as the Proms. He conducted them for nearly half a century, introducing hundreds of new works to British audiences. After his death, the concerts were officially renamed in his honour as the "Henry Wood Promenade Concerts", although they continued to be generally referred to as "the Proms".

The Queen's Hall was a concert hall in Langham Place, London, opened in 1893. Designed by the architect Thomas Knightley, it had room for an audience of about 2,500 people. It became London's principal concert venue. From 1895 until 1941, it was the home of the promenade concerts founded by Robert Newman together with Henry Wood. The hall had drab decor and cramped seating but superb acoustics. It became known as the "musical centre of the [British] Empire", and several of the leading musicians and composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries performed there, including Claude Debussy, Edward Elgar, Maurice Ravel and Richard Strauss.

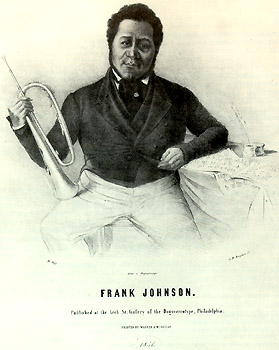

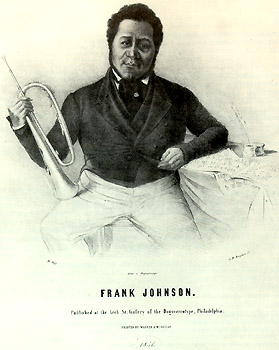

Francis "Frank" Johnson was an American musician and prolific composer during the Antebellum period. African American composers were rare in the U.S. during this period, but Johnson was among the few who were successful. Performing as a virtuoso of the keyed Kent bugle and the violin, he wrote more than two hundred compositions of various styles—operatic airs, Ethiopian minstrel songs, patriotic marches, ballads, cotillions, quadrilles, quicksteps and other dances. Only manuscripts and piano transcriptions survive today.

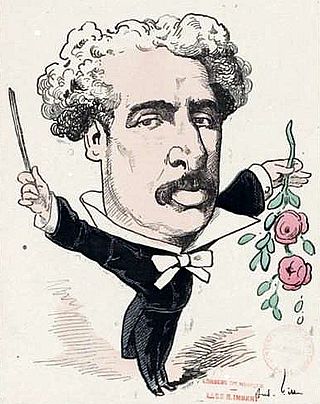

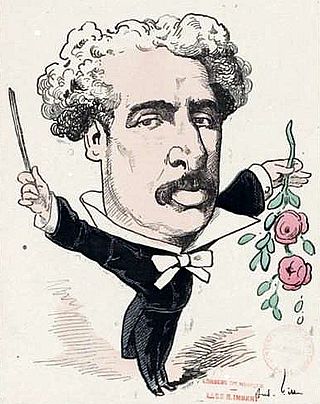

Louis George Maurice Adolphe Roche Albert Abel Antonio Alexandre Noë Jean Lucien Daniel Eugène Joseph-le-brun Joseph-Barême Thomas Thomas Thomas-Thomas Pierre Arbon Pierre-Maurel Barthélemi Artus Alphonse Bertrand Dieudonné Emanuel Josué Vincent Luc Michel Jules-de-la-plane Jules-Bazin Julio César Jullien, who shortened his name to Louis-Antoine Jullien, was a French conductor and composer of light music.

Igor Borisovich Markevitch was a Ukrainian-born composer and conductor who studied and worked in Paris and became a naturalized Italian and French citizen in 1947 and 1982 respectively. He was commissioned in 1929 for a piano concerto by impresario Serge Diaghilev of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo.

Vernon George "Tod" Handley was a British conductor, known in particular for his support of British composers.

Promenade concerts were musical performances in the 18th and 19th century pleasure gardens of London, where the audience would stroll about while listening to the music. The term derives from the French se promener, "to walk".

Adam Von Ahnen Carse was an English composer, academic, music writer and editor, remembered today for his studies on the history of instruments and the orchestra, and for his educational music. His collection of around 350 antique wind instruments is now in the Horniman Museum.

"Le beau monde", Op. 199, is a quadrille composed by Johann Strauss II in 1857, while Strauss was conducting a tour of Russia with his orchestra. The work exudes the authentic musical flavour of Russia, and the Saint Petersburg edition of the work describes the composition as a Quadrille sur des airs Russes. The title of the quadrille reflects the fashion then in Russia for the French language.

Jean Prosper Guivier was a French musician, best known for his solo performances within in the orchestra of Louis-Antoine Jullien. The son of a Napoleonic soldier, he was brought up in the army before enrolling at the Conservatoire de Paris, where he was expelled. As an early exponent of the ophicleide, Guivier became one of Jullien's core of elite musicians along with other soloists such as Herman Koenig. Ill health forced him to reduce his musical engagements during the 1850s and he supplemented his income by dealing and consulting on the design of brass instruments. He retired to Marseilles in 1860, where he died.

Henri Valentino was a French conductor and violinist. From 1824 to 1832, he was co-conductor of the Paris Opera, where he prepared and conducted the premieres of the first two grand operas, Auber's La muette de Portici and Rossini's Guillaume Tell. From 1832 to 1836, he was First Conductor of the Opéra-Comique, and from 1837 to 1841, conductor of classical music at the Concerts Valentino in a hall on the rue Saint-Honoré in Paris.

Jules-Louis-Olivier Métra was a French composer and conductor.

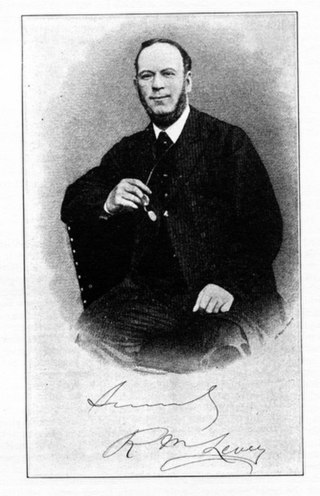

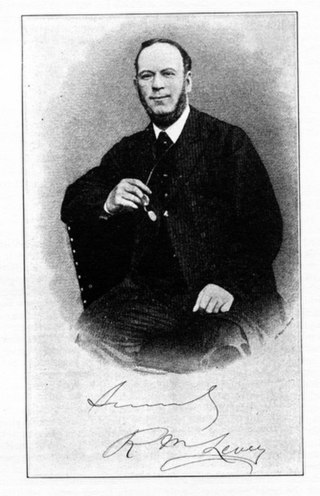

Richard Michael Levey, mostly known as R. M. Levey, was an Irish violinist, conductor, composer, and teacher. He was one of a handful of noted musicians who kept Dublin's concert life in the nineteenth century alive under difficult economic circumstances.

John Alexander Georgiadis was a British violinist and conductor. He was twice Concert Leader with the London Symphony Orchestra during the 1960s and 70s, a member of both the ensembles London Virtuosi and the Gabrieli String Quartet as well as conductor for both the Bangkok Symphony Orchestra and the Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra, and as Director of Orchestral Studies at the Royal Academy of Music.