Related Research Articles

Burundi originated in the 16th century as a small kingdom in the African Great Lakes region. After European contact, it was united with the Kingdom of Rwanda, becoming the colony of Ruanda-Urundi - first colonised by Germany and then by Belgium. The colony gained independence in 1962, and split once again into Rwanda and Burundi. It is one of the few countries in Africa to be a direct territorial continuation of a pre-colonial era African state.

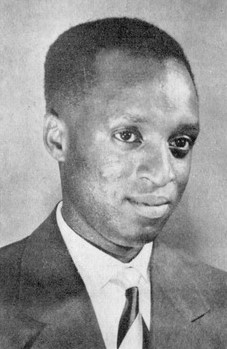

Louis Rwagasore was a Burundian prince and politician, who served as the second prime minister of Burundi for two weeks, from 28 September 1961 until his assassination on 13 October 1961. Born to the Ganwa family of Burundian Mwami (king) Mwambutsa IV in Belgian-administered Ruanda-Urundi in 1932, Rwagasore was educated in Burundian Catholic schools before attending university in Belgium. After he returned to Burundi in the mid-1950s he founded a series of cooperatives to economically empower native Burundians and build up his base of political support. The Belgian administration took over the venture, and as a result of the affair his national profile increased and he became a leading figure of the anti-colonial movement.

Michel Micombero was a Burundian politician and army officer who ruled the country as de facto military dictator for the decade between 1966 and 1976. He was the last Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Burundi from July to November 1966, and the first President of the Republic from November 1966 until his overthrow in 1976.

Mwambutsa IV Bangiricenge was the penultimate king of Burundi who ruled between 1915 and 1966. He succeeded to the throne on the death of his father Mutaga IV Mbikije. Born while Burundi was under German colonial rule, Mwambutsa's reign mostly coincided with Belgian colonial rule (1916–62). The Belgians retained the monarchs of both Rwanda and Burundi under the policy of indirect rule.

Pierre Ngendandumwe was a Burundian politician. He was a member of the Union for National Progress and was an ethnic Hutu. On 18 June 1963, about a year after Burundi gained independence and amidst efforts to bring about political cooperation between Hutus and the dominant minority Tutsis, Ngendandumwe became Burundi's first Hutu prime minister. He served as prime minister until 6 April 1964 and then became prime minister again on 7 January 1965, serving until his death. Eight days after beginning his second term, he was assassinated by a Rwandan Tutsi refugee.

The Kingdom of Burundi or Kingdom of Urundi was a Bantu kingdom in the modern-day Republic of Burundi. The Ganwa monarchs ruled over both Hutus and Tutsis. Created in the 17th century, the kingdom was preserved under German and Belgian colonial rule in the late 19th and early 20th century and was an independent state between 1962 and 1966.

Joseph Bamina was a Burundian politician and member of the Union for National Progress (UPRONA) party. Bamina was Prime Minister from 26 January to 30 September 1965, and President of the Senate of Burundi in 1965. He and other leaders of the government were assassinated on 15 December 1965, by Tutsi soldiers during a reprisal effort to stop a coup by Hutu officers.

Léopold Bihumugani or Biha (1919–2003) was a Burundian politician who served as Prime Minister of Burundi from 13 September 1965 until 8 July 1966. A Ganwa born to a chief in Ruanda-Urundi, he became a close confidant of Mwami Mwambutsa IV in the 1940s after being given charge of a chiefdom which included some of the monarch's property. In the late 1950s he became involved in the Union for National Progress (UPRONA) party as the Belgian colonial administration prepared to grant Burundi its independence. Biha left the party after becoming disenchanted with leader Louis Rwagasore's populist style, and held different roles in transitional governments. He created a new party, Burundi Populaire, but failed to get elected to office and was appointed private secretary to the Mwami after independence.

André Muhirwa (1920–2003) was a Burundian politician who served as prime minister of Burundi from 1961 to 1963. He became prime minister following the assassination of his predecessor, Louis Rwagasore. A member of the Union for National Progress (UPRONA), he previously served as Minister of the Interior from September to October 1961.

The Christian Democratic Party was a political alliance in Burundi.

On 18–19 October 1965, a group of ethnic Hutu officers from the Burundian military and gendarmerie attempted to overthrow Burundi's government in a coup d'état. The rebels were frustrated with Burundi's monarch, Mwami Mwambutsa IV, who had repeatedly attempted to cement his control over the government and bypassed parliamentary norms despite Hutu electoral gains. Although the prime minister was shot and wounded, the coup failed due to the intervention of a contingent of troops led by Captain Michel Micombero.

On 8 July 1966, a coup d'état took place in the Kingdom of Burundi. The second in Burundi's post-independence history, the coup ousted the government loyal to the king (mwami) of Burundi, Mwambutsa IV, who had gone into exile in October 1965 after the failure of an earlier coup d'état.

Paul Mirerekano was a Burundian politician. Ethnically Hutu, he worked as an agronomist for the Belgian colonial administration in Ruanda-Urundi before starting a successful market garden in Bugarama. Politically, he was a nationalist, monarchist, and advocate for Hutu civil rights. He was a leading member of Louis Rwagasore's political party, the Union for National Progress (UPRONA), and in 1961 served as the organisation's interim president. Rwagasore's assassination in 1961 fueled a rivalry between Mirerekano and Prime Minister André Muhirwa, as both men claimed to be the heirs to Rwagasore's legacy and sought to take control of UPRONA. The controversy led to the coalescing of two factions in the party, with Mirerekano leading what became known as the Hutu-dominated "Monrovia group". His criticism of Muhirwa and his successor led him to be arrested on several occasions, but in 1965 he was elected to a seat in the National Assembly representing the Bujumbura constituency. The body subsequently elected Mirerekano its First Vice-President on 20 July. In October Hutu soldiers launched a coup attempt which failed, but led to the outbreak of ethnic violence. The government believed Mirerekano helped plan the coup attempt and executed him. His reputation remains a controversial subject in Burundi.

Joseph Biroli-Baranyanka or Joseph Biroli was a Burundian politician and was the first Burundian to receive a university education. Born in 1929 to a prominent chief, he was a Ganwa of the Batare clan. He performed well as a student and earned a diploma from the Institut universitaire des Territoires d'Outre-Mer in 1953. After continuing his education at several other universities he took up work for the European Economic Community. In 1960 his brother Jean-Baptiste Ntidendereza co-founded the Christian Democratic Party, and Biroli became the party's president. His main political rival was Prince Louis Rwagasore, a Ganwa of the Bezi clan who led the Union for National Progress. Biroli was friendly to the Belgian colonial administration in Ruanda-Urundi, while UPRONA demanded immediate independence.

Jean-Baptiste Ntidendereza was a Burundian politician. A co-founder of the Christian Democratic Party, he served as Minister of Interior of Burundi in 1961. He was later convicted of conspiring to kill Louis Rwagasore, a political opponent, and publicly executed.

The Definitive Constitution of the Kingdom of Burundi, sometimes called the "independence constitution", was the constitution of the independent Kingdom of Burundi from its promulgation in 1962 until its suspension in 1966.

Charles Baranyanka was a Burundian diplomat and historian.

Thaddée Siryuyumunsi was a Burundian politician who served as President of the National Assembly from 1961 to 1965.

The Kamenge incidents or Kamenge riots were a series of armed raids and murders conducted in the Kamenge quarter of Bujumbura, Burundi in January 1962. They were perpetrated by militants of the Jeunesse Nationaliste Rwagasore against Hutu leaders of the Syndicats Chrétiens trade union and the Parti du Peuple. The Kamenge incidents were the first major instance of ethnic violence in modern Burundi.

Joseph Mbazumutima was a Burundian politician.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Weinstein 1976, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 4 Akyeampong & Gates 2012, p. 383.

- 1 2 Lemarchand 1970, p. 314.

- ↑ Chrétien 2016, paragraph 78.

- ↑ Russell 2019, p. 48.

- ↑ Lemarchand 1970, p. 336.

- ↑ Russell 2019, pp. 48, 50.

- 1 2 3 Russell 2019, p. 53.

- ↑ Akyeampong & Gates 2012, pp. 383–384.

- ↑ Russell 2019, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Russell 2019, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Russell 2019, pp. 57–58.

- 1 2 Russell 2019, p. 50.

- ↑ Russell 2019, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Russell 2019, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Russell 2019, p. 54.

- ↑ Russell 2019, p. 59.

- 1 2 Russell 2019, p. 107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Akyeampong & Gates 2012, p. 384.

- ↑ Russell 2019, pp. 42, 50.

- ↑ Russell 2019, p. 49.

- ↑ Russell 2019, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Russell 2019, p. 58.

- ↑ Russell 2019, p. 61.

- ↑ Ghislain 1970, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Russell 2019, p. 65.

- ↑ Russell 2019, pp. 65, 69.

- ↑ Russell 2019, pp. 69–70.

- ↑ Russell 2019, p. 70.

- ↑ Russell 2019, p. 218.

- ↑ Russell 2019, p. 98.

- ↑ Russell 2019, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Russell 2019, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Russell 2019, p. 100.

- ↑ Russell 2019, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Russell 2019, pp. 101–103.

- ↑ Russell 2019, p. 104.

- ↑ Lemarchand 1970, p. 340.

- ↑ Lemarchand 1970, pp. 340–341.

- ↑ Weinstein 1976, pp. 80, 280–281.

- ↑ Lemarchand 1970, pp. 341–342.

- ↑ Russell 2019, p. 125.

- ↑ Russell 2019, p. 128.