The OVRA, whose most probable name was Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism, was the secret police of the Kingdom of Italy, founded in 1927 under the regime of Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini and during the reign of King Victor Emmanuel III. The OVRA was the Italian precursor of the German Gestapo. Mussolini's secret police were assigned to stop any anti-fascist activity or sentiment. Approximately 50,000 OVRA agents infiltrated most aspects of domestic life in Italy. The OVRA, headed by Arturo Bocchini, never appeared in any official document, so the official name of the organization still remains unclear.

Aryanism is an ideology of racial supremacy which views the supposed Aryan race as a distinct and superior racial group which is entitled to rule the rest of humanity. Initially promoted by racist theorists such as Arthur de Gobineau and Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Aryanism reached its peak of influence in Nazi Germany. In the 1930s and 40s, the regime applied the ideology with full force, sparking World War II with the 1939 invasion of Poland in pursuit of Lebensraum, or living space, for the Aryan people. The racial policies which were implemented by the Nazis during the 1930s came to a head during their conquest of Europe and the Soviet Union, culminating in the industrial mass murder of six million Jews and eleven million other victims in what is now known as the Holocaust.

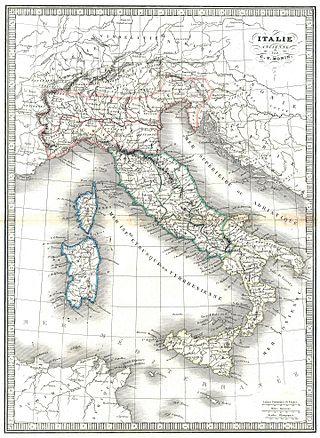

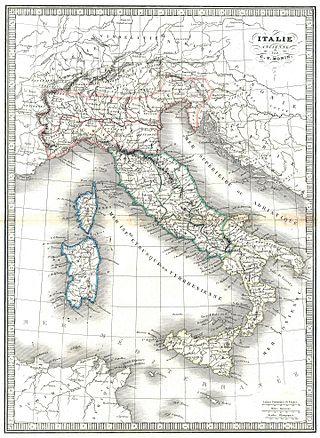

The history of the Jews in Italy spans more than two thousand years to the present. The Jewish presence in Italy dates to the pre-Christian Roman period and has continued, despite periods of extreme persecution and expulsions, until the present. As of 2019, the estimated core Jewish population in Italy numbers around 45,000.

Alexander Stille is an American author and journalist.

The "Manifesto of Race", otherwise referred to as the Charter of Race or the Racial Manifesto, was a manifesto which was promulgated by the Council of Ministers on the 14th of July 1938, its promulgation was followed by the enactment, in October 1938, of the Racial Laws in Fascist Italy (1922–1943) and the Italian colonial empire (1923–1947).

Leone Ginzburg was an Italian editor, writer, journalist and teacher, as well as an important anti-fascist political activist and a hero of the resistance movement. He was the husband of the renowned author Natalia Ginzburg and the father of the historian Carlo Ginzburg.

Ettore Ovazza was an Italian Jewish banker. He was an early financer of Benito Mussolini, of whom he was a personal friend, and Italian fascism, which he supported until the Italian racial laws of 1938. He founded the journal La nostra bandiera. Believing that his position would be restored after the war, Ovazza stayed on after the Germans marched into Italy. Together with his wife and children, shortly after the Fall of Fascism and Mussolini's government during World War II, he was executed near the Swiss border by SS troops in 1943.

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian dictator and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party (PNF). He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 1943, as well as "Duce" of Italian fascism from the establishment of the Italian Fasces of Combat in 1919 until his summary execution in 1945 by Italian partisans. As dictator of Italy and principal founder of fascism, Mussolini inspired and supported the international spread of fascist movements during the inter-war period.

Alain Elkann is an Italian novelist and journalist. Elkann is the conductor of cultural programs on Italian television. He is president of the Scientific Committee of the Italy–USA Foundation. A recurring theme in his books is the history of the Jews in Italy, their centrality to Italian history, and the relation between the Jewish faith and other religions. He is a writer for La Règle du Jeu, Nuovi Argomenti, A, and Shalom magazines.

Carlo Angela was an Italian doctor, who has been recognized as a "Righteous Among the Nations" for his efforts during World War II in saving Jewish lives. He is the father of TV journalist and science writer Piero Angela and grandfather of Alberto Angela.

The Italian racial laws, otherwise referred to as the Racial Laws, were a series of laws which were promulgated by the Mussolini government in Fascist Italy (1922–1943) from 1938 to 1943 in order to enforce racial discrimination and segregation in the Kingdom of Italy. The main victims of the Racial Laws were Italian Jews and the native African inhabitants of the Italian colonial empire (1923–1947). In the aftermath of Mussolini's fall from power, the Badoglio government suppressed the laws. They remained enforced and were made more severe in the territories ruled by the Italian Social Republic (1943–1945) until the end of the Second World War.

Cavalier Angelo Donati was an Italian banker and philanthropist, and a diplomat of the San Marino Republic in Paris.

Regina Coeli is the best known prison in the city of Rome. Previously a Catholic convent, it was built in 1654 in the rione of Trastevere. It started to serve as a prison in 1881.

Initially, Fascist Italy did not enact comprehensive racist policies like those policies which were enacted by its World War II Axis partner Nazi Germany. Italy's National Fascist Party leader, Benito Mussolini, expressed different views on the subject of race over the course of his career. In an interview conducted in 1932 at the Palazzo di Venezia in Rome, he said "Race? It is a feeling, not a reality: ninety-five percent, at least, is a feeling. Nothing will ever make me believe that biologically pure races can be shown to exist today". By 1938, however, he began to actively support racist policies in the Italian Fascist regime, as evidenced by his endorsement of the "Manifesto of Race", the seventh point of which stated that "it is time that Italians proclaim themselves to be openly racist", although Mussolini said that the Manifesto was endorsed "entirely for political reasons", in deference to Nazi German wishes. The "Manifesto of Race", which was published on 14 July 1938, paved the way for the enactment of the Racial Laws. Leading members of the National Fascist Party (PNF), such as Dino Grandi and Italo Balbo, reportedly opposed the Racial Laws. Balbo, in particular, regarded antisemitism as having nothing to do with fascism and he staunchly opposed the antisemitic laws. After 1938, discrimination and persecution intensified and became an increasingly important hallmark of Italian Fascist ideology and policies. Nevertheless, Mussolini and the Italian military did not consistently apply the laws adopted in the Manifesto of Race. In 1943, Mussolini expressed regret for the endorsement, saying that it could've been avoided. After the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, the Italian Fascist government implemented strict racial segregation between white people and black people in Ethiopia.

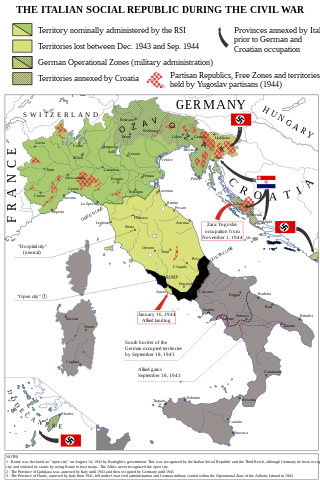

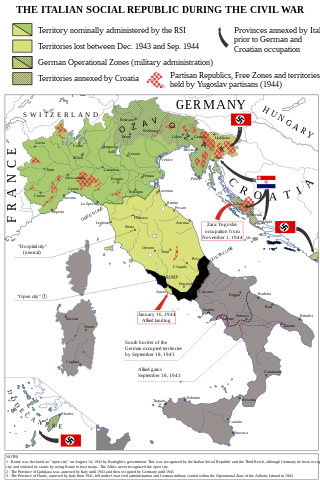

The Holocaust in Italy was the persecution, deportation, and murder of Jews between 1943 and 1945 in the Italian Social Republic, the part of the Kingdom of Italy occupied by Nazi Germany after the Italian surrender on 8 September 1943, during World War II.

The Kingdom of Italy was governed by the National Fascist Party from 1922 to 1943 with Benito Mussolini as prime minister and dictator. The Italian Fascists imposed totalitarian rule and crushed political and intellectual opposition, while promoting economic modernization, traditional social values and a rapprochement with the Roman Catholic Church.

Guido Jung was a successful Jewish-born Italian banker and merchant from Sicily.

Massimo Teglio was an Italian aviator responsible for DELASEM for Northern Italy from 1943 to 1945.

Guido Leto was an Italian police official, head of the OVRA, the secret police of the Fascist regime, from 1938 to 1945. Throughout his career as a policeman he served under the Kingdom of Italy, the Italian Social Republic, and the Italian Republic.

Edvige Mussolini was the younger sister of Arnaldo and Benito Mussolini.