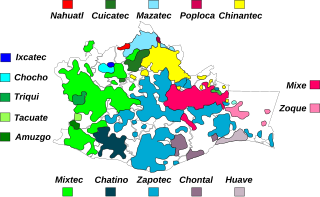

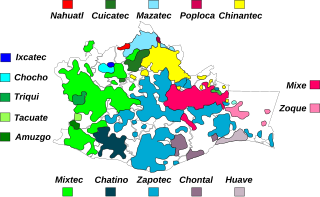

The Zapotec are an indigenous people of Mexico. The population is concentrated in the southern state of Oaxaca, but Zapotec communities also exist in neighboring states. The present-day population is estimated at 400,000 to 650,000 persons, many of whom are monolingual in one of the native Zapotec languages and dialects. In pre-Columbian times, the Zapotec civilization was one of the highly developed cultures of Mesoamerica that had a system of writing.

Oaxaca de Juárez, or simply Oaxaca, is the capital and largest city of the eponymous Mexican state of Oaxaca. It is the municipal seat for the surrounding municipality of Oaxaca. It is in the Centro District in the Central Valleys region of the state, in the foothills of the Sierra Madre at the base of the Cerro del Fortín, extending to the banks of the Atoyac River.

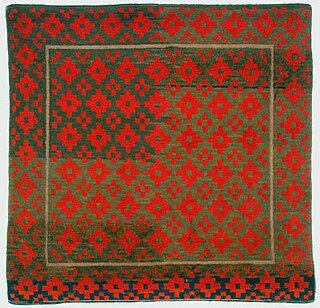

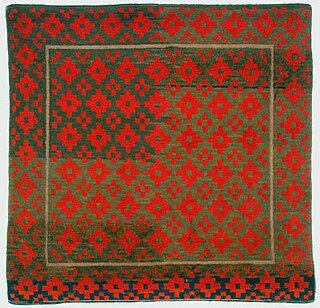

Tibetan rug making is an ancient, traditional craft. Tibetan rugs are traditionally made from Tibetan highland sheep's wool, called changpel. Tibetans use rugs for many purposes ranging from flooring to wall hanging to horse saddles, though the most common use is as a seating carpet. A typical sleeping carpet measuring around 3 ft × 5 ft is called a khaden.

A Persian carpet or Persian rug, also known as Iranian carpet, is a heavy textile made for a wide variety of utilitarian and symbolic purposes and produced in Iran, for home use, local sale, and export. Carpet weaving is an essential part of Persian culture and Iranian art. Within the group of Oriental rugs produced by the countries of the "rug belt", the Persian carpet stands out by the variety and elaborateness of its manifold designs.

Tourism in Mexico holds considerable significance as a pivotal industry within the nation's economic landscape. Beginning in the 1960s, it has been vigorously endorsed by the Mexican government, often heralded as "an industry without smokestacks," signifying its non-polluting and economically beneficial nature. Mexico has consistently ranked among the world's most frequented nations, as documented by the World Tourism Organization. Second only to the United States in the Americas, Mexico's status as a premier tourist destination is underscored by its standing as the sixth-most visited country globally for tourism activities, as of 2017. The country boasts a noteworthy array of UNESCO World Heritage Sites, encompassing ancient ruins, colonial cities, and natural reserves, alongside a plethora of modern public and private architectural marvels. Mexico has attracted foreign visitors beginning in the early nineteenth century, with its cultural festivals, colonial cities, nature reserves and the beach resorts. Mexico's allure to tourists is largely attributed to its temperate climate and distinctive cultural amalgamation, blending European and Mesoamerican influences. The nation experiences peak tourism seasons typically during December and the mid-Summer months. Additionally, brief spikes in visitor numbers occur in the weeks preceding Easter and Spring break, notably drawing college students from the United States to popular beach resort locales.

San Pablo Villa de Mitla is a town and municipality in Mexico which is most famous for being the site of the Mitla archeological ruins. It is part of the Tlacolula District in the east of the Valles Centrales Region. The town is also known for its handcrafted textiles, especially embroidered pieces and mezcal. The town also contains a museum which was closed without explanation in 1995, since when its entire collection of Zapotec and Mixtec cultural items has disappeared. The name “San Pablo” is in honor of Saint Paul, and “Mitla” is a hispanization of the Nahuatl name “Mictlán.” This is the name the Aztecs gave the old pre-Hispanic city before the Spanish arrived and means “land of the dead.” It is located in the Central Valleys regions of Oaxaca, 46 km from the city of Oaxaca, in the District of Tlacolula.

Anatolian rug or Turkish carpet is a term of convenience, commonly used today to denote rugs and carpets woven in Anatolia and its adjacent regions. Geographically, its area of production can be compared to the territories which were historically dominated by the Ottoman Empire. It denotes a knotted, pile-woven floor or wall covering which is produced for home use, local sale, and export, and religious purpose. Together with the flat-woven kilim, Anatolian rugs represent an essential part of the regional culture, which is officially understood as the Culture of Turkey today, and derives from the ethnic, religious and cultural pluralism of one of the most ancient centres of human civilisation.

Maya textiles (k’apak) are the clothing and other textile arts of the Maya peoples, indigenous peoples of the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Belize. Women have traditionally created textiles in Maya society, and textiles were a significant form of ancient Maya art and religious beliefs. They were considered a prestige good that would distinguish the commoners from the elite. According to Brumfiel, some of the earliest weaving found in Mesoamerica can date back to around 1000-800 B.C.E.

Navajo weaving are textiles produced by Navajo people, who are based near the Four Corners area of the United States. Navajo textiles are highly regarded and have been sought after as trade items for more than 150 years. Commercial production of handwoven blankets and rugs has been an important element of the Navajo economy. As one art historian wrote, "Classic Navajo serapes at their finest equal the delicacy and sophistication of any pre-mechanical loom-woven textile in the world."

San Bartolo Coyotepec is a town and municipality located in the center of the Mexican state of Oaxaca. It is in the Centro District of the Valles Centrales region about fifteen km south of the capital of Oaxaca.

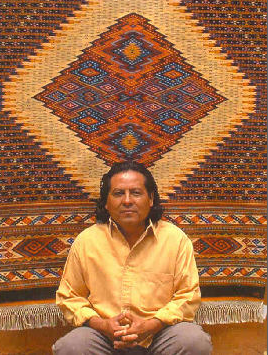

Teotitlán del Valle is a small village and municipality located in the Tlacolula District in the east of the Valles Centrales Region, 31 km from the city of Oaxaca in the foothills of the Sierra Juárez mountains. It is part of the Tlacolula Valley district. It is known for its textiles, especially rugs, which are woven on hand-operated looms, from wool obtained from local sheep and dyed mainly with local, natural dyes. They combine historical Zapotec designs with contemporary designs such as reproductions of famous artists' work. Artists take commissions and participate in tours of family-owned workshops. The name Teotitlán comes from Nahuatl and means "land of the gods." Its Zapotec name is Xaguixe, which means "at the foot of the mountain." Established in 1465, it was one of the first villages founded by Zapotec peoples in this area and retains its Zapotec culture and language.

The textiles of Mexico have a long history. The making of fibers, cloth and other textile goods has existed in the country since at least 1400 BCE. Fibers used during the pre-Hispanic period included those from the yucca, palm and maguey plants as well as the use of cotton in the hot lowlands of the south. After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, the Spanish introduced new fibers such as silk and wool as well as the European foot treadle loom. Clothing styles also changed radically. Fabric was produced exclusively in workshops or in the home until the era of Porfirio Díaz, when the mechanization of weaving was introduced, mostly by the French. Today, fabric, clothes and other textiles are both made by craftsmen and in factories. Handcrafted goods include pre-Hispanic clothing such as huipils and sarapes, which are often embroidered. Clothing, rugs and more are made with natural and naturally dyed fibers. Most handcrafts are produced by indigenous people, whose communities are concentrated in the center and south of the country in states such as Mexico State, Oaxaca and Chiapas. The textile industry remains important to the economy of Mexico although it has suffered a setback due to competition by cheaper goods produced in countries such as China, India and Vietnam.

According to the Mexican government agency Conapo, Oaxaca is the third most economically marginalized states in Mexico. The state has 3.3% of the population but produces only 1.5% of the GNP. The main reason for this is the lack of infrastructure and education, especially in the interior of the state outside of the capital. Eighty percent of the state's municipalities do not meet federal minimums for housing and education. Most development projects are planned for the capital and the surrounding area. Little has been planned for the very rural areas and the state lacks the resources to implement them. The largest sector of Oaxaca's economy is agriculture, mostly done communally in ejidos or similar arrangements. About 31% of the population is employed in agriculture, about 50% in commerce and services and 22% in industry. The commerce sector dominates the gross domestic product at 65.4%, followed by industry/mining at 18.9% and agriculture at 15.7%.

Alice Kagawa Parrott was a Japanese American fiber artist and ceramicist. She spent most of her adult life in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she established a reputation as one of the country's most important weavers, and opened one of Santa Fe's first shops devoted weaving and crafts.

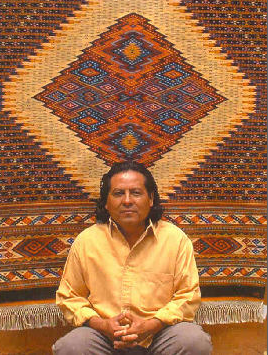

Arnulfo Mendoza Ruíz was an artist, cultural promotor, and weaver who exhibited his work within Mexico and internationally. Born in Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca, a well-known center of Zapotec weaving, he became one of its best-known artisans, recognized as a "Grand Master" by the Fomento cultural Banamex. He also belonged to the founding group of the Taller Rufino Tamayo in Oaxaca, called "The first generation of the Taller Rufino Tamayo" with artists such as Maximino Javier, Alejandro Santiago, Felipe Morales, Filemón Santiago, among others. He worked on the promotion and dissemination of contemporary art and Oaxacan folkart as director of the La Mano Mágica Gallery, together with his ex-wife Mary Jane Gagnier. The gallery and weaving workshop currently directed by his son Gabriel Mendoza Gagngier.

Oaxaca handcrafts and folk art is one of Mexico's important regional traditions of its kind, distinguished by both its overall quality and variety. Producing goods for trade has been an important economic activity in the state, especially in the Central Valleys region since the pre-Hispanic era which the area laid on the trade route between central Mexico and Central America. In the colonial period, the Spanish introduced new raw materials, new techniques and products but the rise of industrially produced products lowered the demand for most handcrafts by the early 20th century. The introduction of highways in the middle part of the century brought tourism to the region and with it a new market for traditional handcrafts. Today, the state boasts the largest number of working artisans in Mexico, producing a wide range of products that continue to grow and evolve to meet changing tastes in the market.

DOBAG is the Turkish acronym for "Doğal Boya Araştırma ve Geliştirme Projesi". The project aims at reviving the traditional Turkish art and craft of carpet weaving. It provides inhabitants of a rural village in Anatolia – mostly female – with a regular source of income. The DOBAG initiative marks the return of the traditional rug production by using hand-spun wool dyed with natural colours, which was subsequently adopted in other rug-producing countries.

D.Y. Begay is a Navajo textile artist born into the Tóʼtsohnii Clan and born from the Táchiiʼnii Clan.

Oaxaca, Mexico, has a high volume of indigenous Zapotec peoples.

Abigail Mendoza Ruiz is a Zapotec chef and co-owner of restaurant Tlamanalli, which she runs with her sisters, in Teotitlán del Valle, Mexico, near Oaxaca. She opened Tlamanalli in February 1990 in order to serve traditional Zapotec cuisine such as mole and squash blossom soup. The restaurant was soon featured in Gourmet magazine. In 1993, her restaurant received a write-up by food critic Molly O'Neill in the New York Times.