Guanajuato, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Guanajuato, is one of the 32 states which make up the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 46 municipalities and its capital city is Guanajuato. The largest city in the state is León.

Museo Universitario de Artes Populares María Teresa Pomar is a museum dedicated to Mexico's handcrafts and folk art tradition, called “artesanía.” It is part of the University of Colima in the city of Colima, founded by artesanía collector and promoter María Terea Pomar. It contains one of the most important collections of its type in Mexico, covering traditions from around the country as well as the artesanía and traditions of the state of Colima.

Cartonería or papier-mâché sculptures are a traditional handcraft in Mexico. The papier-mâché works are also called "carton piedra" for the rigidness of the final product. These sculptures today are generally made for certain yearly celebrations, especially for the Burning of Judas during Holy Week and various decorative items for Day of the Dead. However, they also include piñatas, mojigangas, masks, dolls and more made for various other occasions. There is also a significant market for collectors as well. Papier-mâché was introduced into Mexico during the colonial period, originally to make items for church. Since then, the craft has developed, especially in central Mexico. In the 20th century, the creation of works by Mexico City artisans Pedro Linares and Carmen Caballo Sevilla were recognized as works of art with patrons such as Diego Rivera. The craft has become less popular with more recent generations, but various government and cultural institutions work to preserve it.

The handcrafts of Guerrero include a number of products which are mostly made by the indigenous communities of the Mexican state of Guerrero. Some, like pottery and basketry, have existed relatively intact since the pre Hispanic period, while others have gone through significant changes in technique and design since the colonial period. Today, much of the production is for sale in the state's major tourism centers, Acapulco, Zihuatanejo and Taxco, which has influence the crafts’ modern evolution. The most important craft traditions include amate bark painting, the lacquerware of Olinalá and nearby communities and the silverwork of Taxdo.

María Teresa Pomar was a collector, researcher and promoter of Mexican handcrafts and folk art along with the communities associated with them. She began as a collector then working with museums to promote handcrafts and then working to found a number of museums and other organizations to the same purpose. She became one of Mexico’s foremost experts on the subject, serving as director of different organizations and judge at competitions in Mexico and abroad. She died in 2010 while she was serving as the director of the Museo Universitario de Artes Populares of the University of Colima, which changed its name to honor her.

Lupita dolls, also known as cartonería dolls, are toys made from a very hard kind of papier-mâché which has its origins about 200 years ago in central Mexico. They were originally created as a substitute for the far more expensive porcelain dolls and maintained popularity until the second half of the 20th century, with its availability of plastic dolls. Today they are made only by certain artisans’ workshops in the city of Celaya, as collectors’ items. Since the 1990s, there have been efforts to revitalize the crafts by artists such as María Eugenia Chellet and Carolina Esparragoza sponsored by the government to maintain traditional techniques but update the designs and shapes.

The pottery of Metepec is that of a municipality in central Mexico, located near Mexico City. It is noted for durable utilitarian items but more noted for its decorative and ritual items, especially sculptures called “trees of life,” decorative plaques in sun and moon shapes and mermaid like figures called Tlanchanas. Metepec potters such as the Soteno family have won national and international recognition for their work and the town hosts the annual Concurso Nacional de Alfarería y Cerámica.

Traditional metal working in Mexico dates from the Mesoamerican period with metals such as gold, silver and copper. Other metals were mined and worked starting in the colonial period. The working of gold and silver, especially for jewelry, initially declined after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. However, during the colonial period, the working of metals rose again and took on much of the character traditional goods still have. Today, important metal products include those from silver, gold, copper, iron, tin and more made into jewelry, household objects, furniture, pots, decorative objects, toys and more. Important metal working centers include Taxco for silver, Santa Clara del Cobre for copper, Celaya for tin and Zacatecas for wrought iron.

Traditional Mexican handcrafted toys are those made by artisans rather than manufactured in factories. The history of Mexican toys extends as far back as the Mesoamerican era, but many of the toys date to the colonial period. Many of these were introduced as teaching tools by evangelists, and were associated with certain festivals and holidays. These toys vary widely, including cup and ball, lotería, dolls, miniature people, animals and objects, tops and more—made of many materials, including wood, metal, cloth, corn husks, ceramic, and glass. These toys remained popular throughout Mexico until the mid-20th century, when commercially made, mostly plastic toys became widely available. Because of the advertising commercial toys receive and because they are cheaper, most traditional toys that are sold as handcrafts, principally to tourists and collectors.

Gorky González Quiñones was a Mexican potter who won the Premio Nacional de Ciencias y Artes for his efforts to revive Mexican maiolica pottery. He began in the arts following his father, sculptor Rodolfo González. Although he worked with and studied ceramics in Mexico and Japan, he did not work with maiolica until he received two pieces as part of his antique business. The technique had almost died out in his region, and González Quiñones learned how to make them. His workshop was in Guanajuato, with a client base in Mexico and the United States.

Oaxaca handcrafts and folk art is one of Mexico's important regional traditions of its kind, distinguished by both its overall quality and variety. Producing goods for trade has been an important economic activity in the state, especially in the Central Valleys region since the pre-Hispanic era which the area laid on the trade route between central Mexico and Central America. In the colonial period, the Spanish introduced new raw materials, new techniques and products but the rise of industrially produced products lowered the demand for most handcrafts by the early 20th century. The introduction of highways in the middle part of the century brought tourism to the region and with it a new market for traditional handcrafts. Today, the state boasts the largest number of working artisans in Mexico, producing a wide range of products that continue to grow and evolve to meet changing tastes in the market.

Michoacán handcrafts and folk art is a Mexican regional tradition centered in the state of Michoacán, in central/western Mexico. Its origins traced back to the Purépecha Empire, and later to the efforts to organize and promote trades and crafts by Vasco de Quiroga in what is now the north and northeast of the state. The state has a wide variety of over thirty crafts, with the most important being the working of wood, ceramics, and textiles. A number are more particular to the state, such as the creation of religious images from corn stalk paste, and a type of mosaic made from dyed wheat straw on a waxed board. Though there is support for artisans in the way of contests, fairs, and collective trademarks for certain wares, Michoacán handcrafts lack access to markets, especially those catering to tourists.

Handcrafts and folk art in Mexico City is a microcosm of handcraft production in most of the rest of country. One reason for this is that the city has attracted migration from other parts of Mexico, bringing these crafts. The most important handcraft in the city is the working of a hard paper mache called cartonería, used to make piñatas and other items related to various annual celebrations. It is also used to make fantastic creatures called alebrijes, which originated here in the 20th century. While there are handcrafts made in the city, the capital is better known for selling and promoting crafts from other parts of the country, both fine, very traditional wares and inexpensive curio types, in outlets from fine shops to street markets.

The Mexican State of Mexico produces various kinds of handcrafted items. While not as well documented as the work of other states, it does produce a number of notable items from the pottery of Metepec, the silverwork of the Mazahua people and various textiles including handwoven serapes and rebozos and knotted rugs. There are seventeen recognized handcraft traditions in the state, and include both those with pre Hispanic origins to those brought over by the Spanish after the Conquest. As the state industrializes and competition from cheaper goods increases, handcraft production has diminished. However, there are a number of efforts by state agencies to promote these traditions both inside and outside of Mexico.

Chiapas handcrafts and folk art is most represented with the making of pottery, textiles and amber products, though other crafts such as those working with wood, leather and stone are also important. The state is one of Mexico's main handcraft producers, with most artisans being indigenous women, who dominate the production of pottery and textiles. The making of handcrafts has become economically and socially important in the state, especially since the 1980s, with the rise of the tourist market and artisans’ cooperatives and other organizations. These items generally cannot compete with commercially made goods, but rather are sold for their cultural value, primarily in San Cristóbal de las Casas.

Puebla handcrafts and folk art is handcraft and folk art from the Mexican state of Puebla. The best-known craft of Puebla is Talavera pottery—which is the only mayolica style pottery continuously produced in Mexico since it was introduced in the early colonial period. Other notable handcraft traditions include trees of life from Izúcar de Matamoros and amate (bark) paper made by the very small town of San Pablito in the north of the state. The state also makes glass, Christmas tree ornaments, indigenous textiles, monumental clocks, baskets, and apple cider.

Hidalgo (state) handcrafts and folk art are mostly made for local consumption rather than for collectors, although there have been efforts to promote this work to a wider market. Most are utilitarian and generally simply decorated, if decorated at all. The most important handcraft traditions are pottery, especially in the municipality of Huejutla and textiles, which can be found in diverse parts of the state. Most artisans are indigenous, with the Otomi populations of the Mezquital Valley being the most dominant. Other important handcrafts include basketry, metal and wood working.

Jalisco handcrafts and folk art are noted among Mexican handcraft traditions. The state is one of the main producers of handcrafts, which are noted for quality. The main handcraft tradition is ceramics, which has produced a number of known ceramicists, including Jorge Wilmot, who introduced high fire work into the state. In addition to ceramics, the state also makes blown glass, textiles, wood furniture including the equipal chair, baskets, metal items, piteado and Huichol art.

Tlaxcala handcrafts and folk art is that which comes from the smallest state in Mexico, located in the center-east of the country. Its best-known wares are the "canes of Apizaco", sawdust carpets and the making of Saltillo-style serapes. However, there are other handcraft traditions, such as the making of pottery, including Talavera type wares, cartoneria, metalworking and stone working. The state supports artisans through the activities of the Fideicomiso Fondo de la Casa de las Artesanía de Tlaxcala

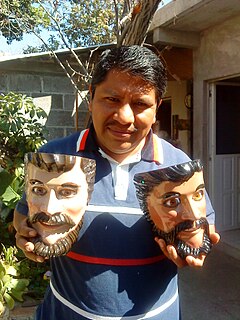

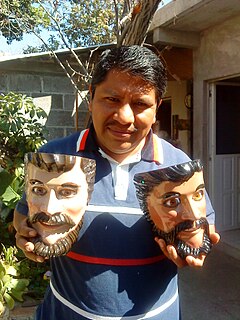

Sotero Lemus Gervacio is a cartonería artisan who is known for his traditional toymaking and large figures. Although situated in the Mexico City metro area, Lemus' work and style is based on the cartonería traditions of Celaya, Guanajuato. He is a fourth-generation "cartonero," from a family who is noted in Celaya for its work. Lemus' work has been sold and exhibited in various parts of the world, including the United States, Europe and Central America. Since 2005, he has also been involved in the making of much larger works for exhibition, starting with a twelve-meter tall image of Don Quixote on horseback, which toured Mexico for about a year.