Fides was the goddess of trust, faithfulness, and good faith in ancient Roman religion. She was one of the original virtues to be considered an actual religious divinity. Fides is everything that is required for "honour and credibility, from fidelity in marriage, to contractual arrangements, and the obligation soldiers owed to Rome." Fides also means reliability, "reliability between two parties, which is always reciprocal." and "bedrock of relations between people and their communities", and then it was turned into a Roman deity and from which we gain the English word, 'fidelity'.

Libitina, also Libentina or Lubentina, is an ancient Roman goddess of funerals and burial. Her name was used as a metonymy for death, and undertakers were known as libitinarii. Libitina was associated with Venus, and the name appears in some authors as an epithet of Venus.

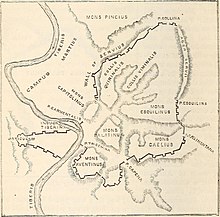

The Aventine Hill is one of the Seven Hills on which ancient Rome was built. It belongs to Ripa, the modern twelfth rione, or ward, of Rome.

The Via Flaminia was an ancient Roman road leading from Rome over the Apennine Mountains to Ariminum (Rimini) on the coast of the Adriatic Sea, and due to the ruggedness of the mountains was the major option the Romans had for travel between Etruria, Latium, Campania, and the Po Valley. The section running through northern Rome is where Constantine the Great, allegedly, had his famous vision of the Chi Rho, leading to his conversion to Christianity and the Christianization of the Roman Empire.

The Via Aurelia is a Roman road in Italy constructed in approximately 241 BC. The project was undertaken by Gaius Aurelius Cotta, who at that time was censor. Cotta had a history of building roads for Rome, as he had overseen the construction of a military road in Sicily connecting Agrigentum and Panormus.

The Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, also known as the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus was the most important temple in Ancient Rome, located on the Capitoline Hill. It was surrounded by the Area Capitolina, a precinct where numerous shrines, altars, statues and victory trophies were displayed.

The Milliarium Aureum, also known by the translation Golden Milestone, was a monument, probably of marble or gilded bronze, erected by the Emperor Augustus near the Temple of Saturn in the central Forum of Ancient Rome. All roads were considered to begin at this monument and all distances in the Roman Empire were measured relative to it. On it perhaps were listed all the major cities in the empire and distances to them, though the monument's precise location and inscription remain matters of debate among historians.

The Porta del Popolo, or Porta Flaminia, is a city gate of the Aurelian Walls of Rome that marks the border between Piazza del Popolo and Piazzale Flaminio.

The Porta Esquilina was a gate in the Servian Wall, of which the Arch of Gallienus is extant today. Tradition dates it back to the 6th century BC, when the Servian Wall was said to have been built by the Roman king Servius Tullius. However modern scholarship and evidence from archaeology indicate a date in the fourth century BC. The archway of the gate was rededicated in 262 as the Arch of Gallienus.

The Pons Aemilius is the oldest Roman stone bridge in Rome. Preceded by a wooden version, it was rebuilt in stone in the 2nd century BC. It once spanned the Tiber, connecting the Forum Boarium, the Roman cattle market, on the east with Trastevere on the west. A single arch in mid-river is all that remains today, lending the bridge its name Ponte Rotto.

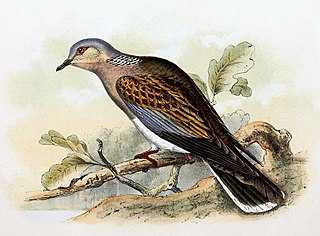

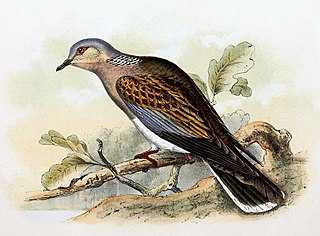

In ancient Roman religion and myth, the Querquetulanae or Querquetulanae virae were nymphs of the oak grove at a stage of producing green growth. Their sacred grove (lucus) was within the Porta Querquetulana, a gate in the Servian Wall. According to Festus, it was believed that in Rome there was once an oakwood within the Porta Querquetulana onto the greening of which presided the virae Querquetulanae.

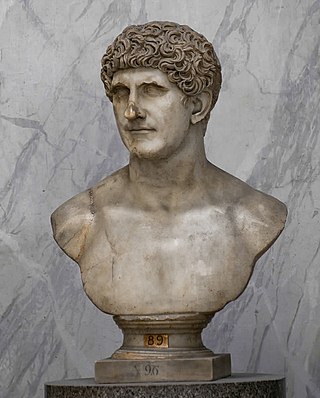

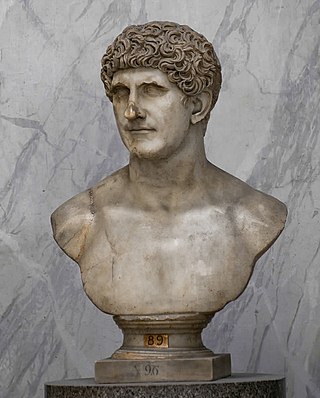

The gens Antonia was a Roman family of great antiquity, with both patrician and plebeian branches. The first of the gens to achieve prominence was Titus Antonius Merenda, one of the second group of Decemviri called, in 450 BC, to help draft what became the Law of the Twelve Tables. The most prominent member of the gens was Marcus Antonius.

In ancient Rome, the Piscina Publica was a public reservoir and swimming pool located in Regio XII. The region itself came to be called informally Piscina Publica from the landmark. The piscina was situated in the low-lying area between the Via Appia, the Servian Wall, and the northeast slope of the Aventine Hill, an area later occupied by the Baths of Caracalla.

The Porta Caelimontana or Celimontana was a gate in the Servian Wall on the rise of the Caelian Hill.

The Arch of Dolabella and Silanus or Arch of Dolabella is an ancient Roman arch. It was built by senatorial decree in 10 AD by the consuls P. Cornelius Dolabella and C. Junius Silanus.

The lautumiae were tufa quarries that became a topographical marker in ancient Rome. They were located on the northeast slope of the Capitoline Hill, forming one side of the Graecostasis, where foreign embassies gathered prior to appearing before the Roman Senate.

The Porta Querquetulana or Querquetularia was a gateway in the Servian Wall, named after the sacred grove of the Querquetulanae adjacent to and just within it. The grove appears not to have still existed in the latter 1st century BC.

The Alta Semita was a street in ancient Rome that gave its name to one of the 14 regions of Augustan Rome.

The Carmental Gate, also known by its Latin name as the Porta Carmentalis, was a double gate in the Servian Walls of ancient Rome. It was named for a nearby shrine to the goddess or nymph Carmenta, whose importance in early Roman religion is also indicated by the assignment of one of the fifteen flamines to her cult, and by the archaic festival in her honor, the Carmentalia. The shrine was to the right as one exited the gate.

The Regio II Caelimontium is the second regio of imperial Rome, under Augustus's administrative reform. It took its name from the Caelian Hill, which the region was centred on.