Black is a racialized classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid- to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin; in certain countries, often in socially based systems of racial classification in the Western world, the term "black" is used to describe persons who are perceived as dark-skinned compared to other populations. It is most commonly used for people of sub-Saharan African ancestry, Indigenous Australians and Melanesians, though it has been applied in many contexts to other groups, and is no indicator of any close ancestral relationship whatsoever. Indigenous African societies do not use the term black as a racial identity outside of influences brought by Western cultures.

African-American music is a broad term covering a diverse range of musical genres largely developed by African Americans and their culture. Its origins are in musical forms that developed as a result of the enslavement of African Americans prior to the American Civil War. It has been said that "every genre that is born from America has black roots."

An African American is a citizen or resident of the United States who has origins in any of the black populations of Africa. African American-related topics include:

The Black Arts Movement (BAM) was an African American-led art movement that was active during the 1960s and 1970s. Through activism and art, BAM created new cultural institutions and conveyed a message of black pride. The movement expanded from the incredible accomplishments of artists of the Harlem Renaissance.

Black History Month is an annual observance originating in the United States, where it is also known as African-American History Month. It has received official recognition from governments in the United States and Canada, and more recently has been observed in Ireland and the United Kingdom. It began as a way of remembering important people and events in the history of the African diaspora. It is celebrated in February in the United States and Canada, while in Ireland and the United Kingdom it is observed in October.

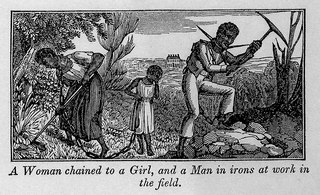

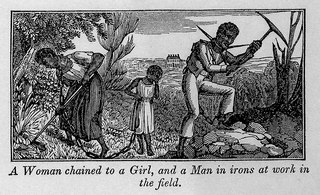

African American history started with the arrival of Africans to North America in the 16th and 17th centuries. Former Spanish slaves who had been freed by Francis Drake arrived aboard the Golden Hind at New Albion in California in 1579. The European colonization of the Americas, and the resulting Atlantic slave trade, led to a large-scale transportation of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic; of the roughly 10–12 million Africans who were sold by the Barbary slave trade, either to European slavery or to servitude in the Americas, approximately 388,000 landed in North America. After arriving in various European colonies in North America, the enslaved Africans were sold to white colonists, primarily to work on cash crop plantations. A group of enslaved Africans arrived in the English Virginia Colony in 1619, marking the beginning of slavery in the colonial history of the United States; by 1776, roughly 20% of the British North American population was of African descent, both free and enslaved.

African-American culture, also known as Black American Culture or Black Culture in American English, refers to the cultural expressions of African Americans, either as part of or distinct from mainstream American culture. African-American culture has been influential on American and global worldwide culture as a whole.

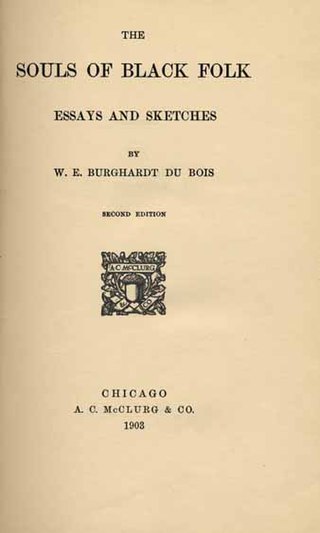

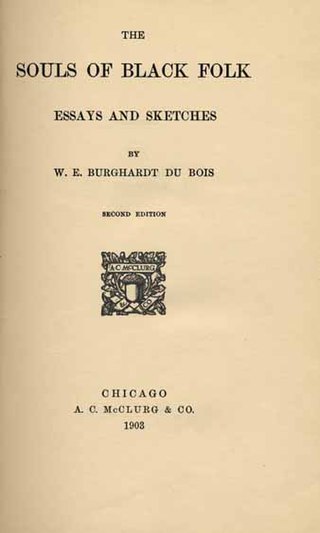

The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches is a 1903 work of American literature by W. E. B. Du Bois. It is a seminal work in the history of sociology and a cornerstone of African-American literature.

Double consciousness is the dual self-perception experienced by subordinated or colonized groups in an oppressive society. The term and the idea were first published in W. E. B. Du Bois's autoethnographic work, The Souls of Black Folk in 1903, in which he described the African American experience of double consciousness, including his own.

Nelson George is an American author, columnist, music and culture critic, journalist, and filmmaker. He has been nominated twice for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

"New Negro" is a term popularized during the Harlem Renaissance implying a more outspoken advocacy of dignity and a refusal to submit quietly to the practices and laws of Jim Crow racial segregation. The term "New Negro" was made popular by Alain LeRoy Locke in his anthology The New Negro.

Black American princess (BAP) is a (sometimes) pejorative term for African-American women of upper- and upper-middle-class background, who possess a spoiled or materialistic demeanor. While carrying "valley girl" overtones of the overly materialistic and style-conscious egotist, the term has also been reclaimed as a matter of racial pride to cover an indulged, but not necessarily spoiled or shallow, daughter of the emerging buppies or black urban middle class. At best, such figures carry with them through life a sense of civic pride, and of responsibility for giving back to their community.

Alice Dunbar Nelson was an American poet, journalist, and political activist. Among the first generation of African Americans born free in the Southern United States after the end of the American Civil War, she was one of the prominent African Americans involved in the artistic flourishing of the Harlem Renaissance. Her first husband was the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. After his death, she married physician Henry A. Callis; and, lastly, was married to Robert J. Nelson, a poet and civil rights activist. She achieved prominence as a poet, author of short stories and dramas, newspaper columnist, women's rights activist, and editor of two anthologies.

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the time, it was known as the "New Negro Movement", named after The New Negro, a 1925 anthology edited by Alain Locke. The movement also included the new African American cultural expressions across the urban areas in the Northeast and Midwest United States affected by a renewed militancy in the general struggle for civil rights, combined with the Great Migration of African American workers fleeing the racist conditions of the Jim Crow Deep South, as Harlem was the final destination of the largest number of those who migrated north.

Trey Ellis is an American novelist, screenwriter, professor, playwright, and essayist. He was born in Washington D.C. and graduated from Hopkins School and Phillips Academy, Andover, where he studied under Alexander Theroux before attending Stanford University, where he was the editor of the Stanford Chaparral and wrote his first novel, Platitudes in a creative writing class taught by Gilbert Sorrentino. He is a professor of Professional Practice in the Graduate School of the Arts at Columbia University.

Mark Anthony Neal is an American author and academic. He is the Professor of Black Popular Culture in the Department of African and African-American Studies at Duke University, where he won the 2010 Robert B. Cox Award for Teaching. Neal has written and lectured extensively on black popular culture, black masculinity, sexism and homophobia in Black communities, and the history of popular music.

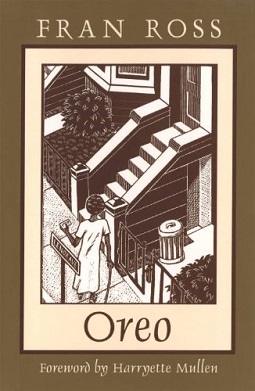

Oreo is a 1974 satirical novel by American writer Fran Ross, a journalist and, briefly, a comedy writer for Richard Pryor. The novel, addressing issues of a mixed-heritage child, was considered "before its time" and went out of print until Harryette Mullen rediscovered the novel and brought it out of obscurity.

Black power is a political slogan and a name which is given to various associated ideologies which aim to achieve self-determination for black people. It is primarily, but not exclusively, used by black people activists and proponents of what the slogan entails in the United States. The black power movement was prominent in the late 1960s and early 1970s, emphasizing racial pride and the creation of black political and cultural institutions to nurture, promote and advance what was seen by proponents of the movement as being the collective interests and values of black Americans.

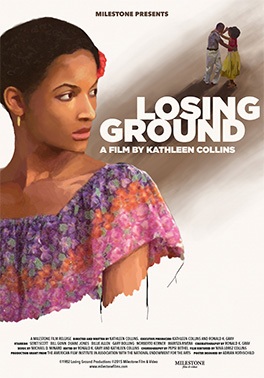

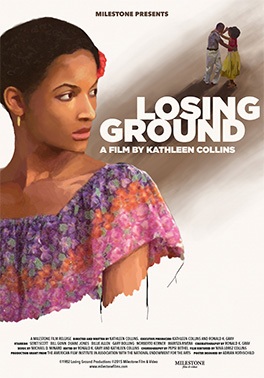

Losing Ground is a semiautobiographical 1982 American drama film written and directed by Kathleen Collins, and starring Seret Scott, Bill Gunn and Duane Jones. It is the first feature-length drama directed by an African American woman since the 1920s and won First Prize at the Figueira da Foz International Film Festival in Portugal.

Blaxicans are Americans who are both Black and Mexican American descent. Some may prefer to identify as Afro-Chicano or Black Chicana/o and embrace Chicano identity, culture, and political consciousness. Most Blaxicans have origins in working class community interactions between African Americans and Mexican Americans. Los Angeles has been cited as the hub for Blaxican culture. In 2010, it was recorded that 42,000 people in Los Angeles County identified as both Black and Latino, most of whom are believed to be both Black and Mexican American.