Related Research Articles

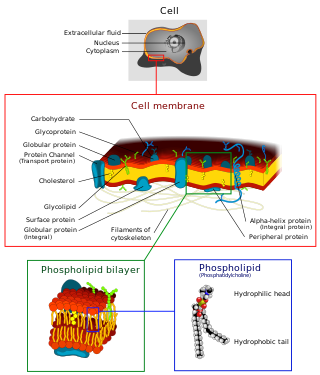

A biological membrane, biomembrane or cell membrane is a selectively permeable membrane that separates the interior of a cell from the external environment or creates intracellular compartments by serving as a boundary between one part of the cell and another. Biological membranes, in the form of eukaryotic cell membranes, consist of a phospholipid bilayer with embedded, integral and peripheral proteins used in communication and transportation of chemicals and ions. The bulk of lipids in a cell membrane provides a fluid matrix for proteins to rotate and laterally diffuse for physiological functioning. Proteins are adapted to high membrane fluidity environment of the lipid bilayer with the presence of an annular lipid shell, consisting of lipid molecules bound tightly to the surface of integral membrane proteins. The cell membranes are different from the isolating tissues formed by layers of cells, such as mucous membranes, basement membranes, and serous membranes.

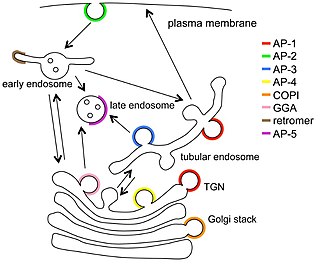

The endomembrane system is composed of the different membranes (endomembranes) that are suspended in the cytoplasm within a eukaryotic cell. These membranes divide the cell into functional and structural compartments, or organelles. In eukaryotes the organelles of the endomembrane system include: the nuclear membrane, the endoplasmic reticulum, the Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, vesicles, endosomes, and plasma (cell) membrane among others. The system is defined more accurately as the set of membranes that forms a single functional and developmental unit, either being connected directly, or exchanging material through vesicle transport. Importantly, the endomembrane system does not include the membranes of plastids or mitochondria, but might have evolved partially from the actions of the latter.

Endocytosis is a cellular process in which substances are brought into the cell. The material to be internalized is surrounded by an area of cell membrane, which then buds off inside the cell to form a vesicle containing the ingested materials. Endocytosis includes pinocytosis and phagocytosis. It is a form of active transport.

In cell biology, a vesicle is a structure within or outside a cell, consisting of liquid or cytoplasm enclosed by a lipid bilayer. Vesicles form naturally during the processes of secretion (exocytosis), uptake (endocytosis), and the transport of materials within the plasma membrane. Alternatively, they may be prepared artificially, in which case they are called liposomes. If there is only one phospholipid bilayer, the vesicles are called unilamellar liposomes; otherwise they are called multilamellar liposomes. The membrane enclosing the vesicle is also a lamellar phase, similar to that of the plasma membrane, and intracellular vesicles can fuse with the plasma membrane to release their contents outside the cell. Vesicles can also fuse with other organelles within the cell. A vesicle released from the cell is known as an extracellular vesicle.

Exocytosis is a form of active transport and bulk transport in which a cell transports molecules out of the cell. As an active transport mechanism, exocytosis requires the use of energy to transport material. Exocytosis and its counterpart, endocytosis, are used by all cells because most chemical substances important to them are large polar molecules that cannot pass through the hydrophobic portion of the cell membrane by passive means. Exocytosis is the process by which a large amount of molecules are released; thus it is a form of bulk transport. Exocytosis occurs via secretory portals at the cell plasma membrane called porosomes. Porosomes are permanent cup-shaped lipoprotein structure at the cell plasma membrane, where secretory vesicles transiently dock and fuse to release intra-vesicular contents from the cell.

In biology, caveolae, which are a special type of lipid raft, are small invaginations of the plasma membrane in the cells of many vertebrates. They are the most abundant surface feature of many vertebrate cell types, especially endothelial cells, adipocytes and embryonic notochord cells. They were originally discovered by E. Yamada in 1955.

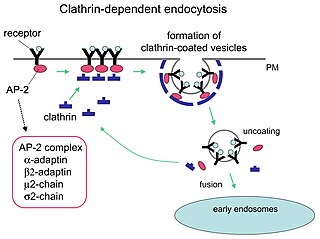

Clathrin is a protein that plays a major role in the formation of coated vesicles. Clathrin was first isolated by Barbara Pearse in 1976. It forms a triskelion shape composed of three clathrin heavy chains and three light chains. When the triskelia interact they form a polyhedral lattice that surrounds the vesicle. The protein's name refers to this lattice structure, deriving from Latin clathri meaning lattice. Barbara Pearse named the protein clathrin at the suggestion of Graeme Mitchison, selecting it from three possible options. Coat-proteins, like clathrin, are used to build small vesicles in order to transport molecules within cells. The endocytosis and exocytosis of vesicles allows cells to communicate, to transfer nutrients, to import signaling receptors, to mediate an immune response after sampling the extracellular world, and to clean up the cell debris left by tissue inflammation. The endocytic pathway can be hijacked by viruses and other pathogens in order to gain entry to the cell during infection.

Endosomes are a collection of intracellular sorting organelles in eukaryotic cells. They are parts of the endocytic membrane transport pathway originating from the trans Golgi network. Molecules or ligands internalized from the plasma membrane can follow this pathway all the way to lysosomes for degradation or can be recycled back to the cell membrane in the endocytic cycle. Molecules are also transported to endosomes from the trans Golgi network and either continue to lysosomes or recycle back to the Golgi apparatus.

The plasma membranes of cells contain combinations of glycosphingolipids, cholesterol and protein receptors organised in glycolipoprotein lipid microdomains termed lipid rafts. Their existence in cellular membranes remains controversial. Indeed, Kervin and Overduin imply that lipid rafts are misconstrued protein islands, which they propose form through a proteolipid code. Nonetheless, it has been proposed that they are specialized membrane microdomains which compartmentalize cellular processes by serving as organising centers for the assembly of signaling molecules, allowing a closer interaction of protein receptors and their effectors to promote kinetically favorable interactions necessary for the signal transduction. Lipid rafts influence membrane fluidity and membrane protein trafficking, thereby regulating neurotransmission and receptor trafficking. Lipid rafts are more ordered and tightly packed than the surrounding bilayer, but float freely within the membrane bilayer. Although more common in the cell membrane, lipid rafts have also been reported in other parts of the cell, such as the Golgi apparatus and lysosomes.

In cellular biology, pinocytosis, otherwise known as fluid endocytosis and bulk-phase pinocytosis, is a mode of endocytosis in which small molecules dissolved in extracellular fluid are brought into the cell through an invagination of the cell membrane, resulting in their containment within a small vesicle inside the cell. These pinocytotic vesicles then typically fuse with early endosomes to hydrolyze the particles.

Receptor-mediated endocytosis (RME), also called clathrin-mediated endocytosis, is a process by which cells absorb metabolites, hormones, proteins – and in some cases viruses – by the inward budding of the plasma membrane (invagination). This process forms vesicles containing the absorbed substances and is strictly mediated by receptors on the surface of the cell. Only the receptor-specific substances can enter the cell through this process.

In biology, cell signaling is the process by which a cell interacts with itself, other cells, and the environment. Cell signaling is a fundamental property of all cellular life in prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Vesicular transport adaptor proteins are proteins involved in forming complexes that function in the trafficking of molecules from one subcellular location to another. These complexes concentrate the correct cargo molecules in vesicles that bud or extrude off of one organelle and travel to another location, where the cargo is delivered. While some of the details of how these adaptor proteins achieve their trafficking specificity has been worked out, there is still much to be learned.

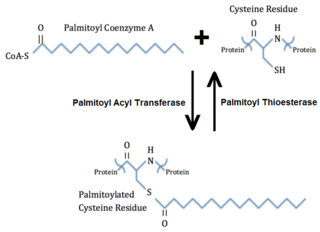

Palmitoylation is the covalent attachment of fatty acids, such as palmitic acid, to cysteine (S-palmitoylation) and less frequently to serine and threonine (O-palmitoylation) residues of proteins, which are typically membrane proteins. The precise function of palmitoylation depends on the particular protein being considered. Palmitoylation enhances the hydrophobicity of proteins and contributes to their membrane association. Palmitoylation also appears to play a significant role in subcellular trafficking of proteins between membrane compartments, as well as in modulating protein–protein interactions. In contrast to prenylation and myristoylation, palmitoylation is usually reversible (because the bond between palmitic acid and protein is often a thioester bond). The reverse reaction in mammalian cells is catalyzed by acyl-protein thioesterases (APTs) in the cytosol and palmitoyl protein thioesterases in lysosomes. Because palmitoylation is a dynamic, post-translational process, it is believed to be employed by the cell to alter the subcellular localization, protein–protein interactions, or binding capacities of a protein.

-Cytosis is a suffix that either refers to certain aspects of cells ie cellular process or phenomenon or sometimes refers to predominance of certain type of cells. It essentially means "of the cell". Sometimes it may be shortened to -osis and may be related to some of the processes ending with -esis or similar suffixes.

The active zone or synaptic active zone is a term first used by Couteaux and Pecot-Dechavassinein in 1970 to define the site of neurotransmitter release. Two neurons make near contact through structures called synapses allowing them to communicate with each other. As shown in the adjacent diagram, a synapse consists of the presynaptic bouton of one neuron which stores vesicles containing neurotransmitter, and a second, postsynaptic neuron which bears receptors for the neurotransmitter, together with a gap between the two called the synaptic cleft. When an action potential reaches the presynaptic bouton, the contents of the vesicles are released into the synaptic cleft and the released neurotransmitter travels across the cleft to the postsynaptic neuron and activates the receptors on the postsynaptic membrane.

The cell membrane is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment. The cell membrane consists of a lipid bilayer, made up of two layers of phospholipids with cholesterols interspersed between them, maintaining appropriate membrane fluidity at various temperatures. The membrane also contains membrane proteins, including integral proteins that span the membrane and serve as membrane transporters, and peripheral proteins that loosely attach to the outer (peripheral) side of the cell membrane, acting as enzymes to facilitate interaction with the cell's environment. Glycolipids embedded in the outer lipid layer serve a similar purpose. The cell membrane controls the movement of substances in and out of a cell, being selectively permeable to ions and organic molecules. In addition, cell membranes are involved in a variety of cellular processes such as cell adhesion, ion conductivity, and cell signalling and serve as the attachment surface for several extracellular structures, including the cell wall and the carbohydrate layer called the glycocalyx, as well as the intracellular network of protein fibers called the cytoskeleton. In the field of synthetic biology, cell membranes can be artificially reassembled.

Intracellular transport is the movement of vesicles and substances within a cell. Intracellular transport is required for maintaining homeostasis within the cell by responding to physiological signals. Proteins synthesized in the cytosol are distributed to their respective organelles, according to their specific amino acid’s sorting sequence. Eukaryotic cells transport packets of components to particular intracellular locations by attaching them to molecular motors that haul them along microtubules and actin filaments. Since intracellular transport heavily relies on microtubules for movement, the components of the cytoskeleton play a vital role in trafficking vesicles between organelles and the plasma membrane by providing mechanical support. Through this pathway, it is possible to facilitate the movement of essential molecules such as membrane‐bounded vesicles and organelles, mRNA, and chromosomes.

Substrate presentation is a biological process that activates a protein. The protein is sequestered away from its substrate and then activated by release and exposure of the protein to its substrate. A substrate is typically the substance on which an enzyme acts but can also be a protein surface to which a ligand binds. The substrate is the material acted upon. In the case of an interaction with an enzyme, the protein or organic substrate typically changes chemical form. Substrate presentation differs from allosteric regulation in that the enzyme need not change its conformation to begin catalysis. Substrate presentation is best described for domain partitioning at nanoscopic distances (<100 nm).

Clathrin-independent endocytosis refers to the cellular process by which cells internalize extracellular molecules and particles through mechanisms that do not rely on the protein clathrin, playing a crucial role in diverse physiological processes such as nutrient uptake, membrane turnover, and cellular signaling.

References

- 1 2 Widmaier, Eric P.; Hershel Raff; Kevin T. Strang (2008). Vander's Human Physiology, 11th Ed . McGraw-Hill. pp. 114. ISBN 978-0-07-304962-5.

- ↑ Mineo, C.; Anderson, R.G. (August 2001). "Potocytosis. Robert Feulgen Lecture". Histochem Cell Biology. 116 (2): 109–18. doi:10.1007/s004180100289. PMID 11685539.

- ↑ Lajoie, Patrick; Nabi, Ivan R. (2010). "Lipid rafts, caveolae, and their endocytosis". International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology. 282: 135–163. doi:10.1016/S1937-6448(10)82003-9. ISBN 9780123812568. ISSN 1937-6448. PMID 20630468.

- ↑ Anderson, R. G. (March 1993). "Potocytosis of small molecules and ions by caveolae". Trends in Cell Biology. 3 (3): 69–72. doi:10.1016/0962-8924(93)90065-9. ISSN 0962-8924. PMID 14731772.