Related Research Articles

Maria Theresa was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position suo jure. She was the sovereign of Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Bohemia, Transylvania, Mantua, Milan, Galicia and Lodomeria, the Austrian Netherlands, and Parma. By marriage, she was Duchess of Lorraine, Grand Duchess of Tuscany, and Holy Roman Empress.

Charles VII was Prince-Elector of Bavaria from 26 February 1726 and Holy Roman Emperor from 24 January 1742 to his death. He was also King of Bohemia from 1741 to 1743. Charles was a member of the House of Wittelsbach, and his reign as Holy Roman Emperor thus marked the end of three centuries of uninterrupted Habsburg imperial rule, although he was related to the Habsburgs by both blood and marriage.

Joseph I was Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of the Austrian Habsburg monarchy from 1705 until his death in 1711. He was the eldest son of Emperor Leopold I from his third wife, Eleonor Magdalene of Neuburg. Joseph was crowned King of Hungary at the age of nine in 1687 and was elected King of the Romans at the age of eleven in 1690. He succeeded to the thrones of Bohemia and the Holy Roman Empire when his father died.

Leopold I was Holy Roman Emperor, King of Hungary, Croatia, and Bohemia. The second son of Ferdinand III, Holy Roman Emperor, by his first wife, Maria Anna of Spain, Leopold became heir apparent in 1654 after the death of his elder brother Ferdinand IV. Elected in 1658, Leopold ruled the Holy Roman Empire until his death in 1705, becoming the second longest-ruling Habsburg emperor. He was both a composer and considerable patron of music.

Charles VI was Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of the Austrian Habsburg monarchy from 1711 until his death, succeeding his elder brother, Joseph I. He unsuccessfully claimed the throne of Spain following the death of his relative, Charles II. In 1708, he married Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, by whom he had his four children: Leopold Johann, Maria Theresa, Maria Anna, and Maria Amalia.

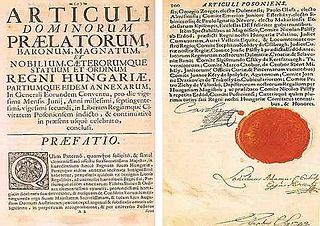

The Pragmatic Sanction was an edict issued by Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI, on 19 April 1713 to ensure that the Habsburg monarchy, which included the Archduchy of Austria, the Kingdom of Hungary, the Kingdom of Croatia, the Kingdom of Bohemia, the Duchy of Milan, the Kingdom of Naples, the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Austrian Netherlands, could be inherited by a daughter undivided.

A pragmatic sanction is a sovereign's solemn decree on a matter of primary importance and has the force of fundamental law. In the late history of the Holy Roman Empire, it referred more specifically to an edict issued by the Emperor.

The Silesian Wars were three wars fought in the mid-18th century between Prussia and Habsburg Austria for control of the Central European region of Silesia. The First (1740–1742) and Second (1744–1745) Silesian Wars formed parts of the wider War of the Austrian Succession, in which Prussia was a member of a coalition seeking territorial gain at Austria's expense. The Third Silesian War (1756–1763) was a theatre of the global Seven Years' War, in which Austria in turn led a coalition of powers aiming to seize Prussian territory.

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities that were ruled by the House of Habsburg and, following the partition of the dynasty, especially by its Austrian branch. From the 18th century it is also referred to as the Danubian monarchy or the Austrian monarchy.

Maximilian III Joseph, "the much beloved", was a Prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire and Duke of Bavaria from 1745 to 1777. He was the last of the Bavarian branch of the house of Wittelsbach and because of his death, the war of Bavarian Succession broke out.

The Kingdom of Hungary between 1526 and 1867 existed as a state outside the Holy Roman Empire, but part of the lands of the Habsburg monarchy that became the Austrian Empire in 1804. After the Battle of Mohács in 1526, the country was ruled by two crowned kings. Initially, the exact territory under Habsburg rule was disputed because both rulers claimed the whole kingdom. This unsettled period lasted until 1570 when John Sigismund Zápolya abdicated as King of Hungary in Emperor Maximilian II's favor.

Maria Josepha of Austria was the Queen of Poland and Electress of Saxony by marriage to Augustus III. From 1711 to 1717, she was heir presumptive to the Habsburg Empire. Her sister Maria Amalia became Electress of Bavaria.

Eleonore Magdalene Therese of Neuburg was Holy Roman Empress, German Queen, Archduchess of Austria, Queen of Hungary and Bohemia as the third and final wife of Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor. Before her marriage and during her widowhood, she led an ascetic and monastic life, translating the Bible from Latin to German and defended the Order of the Discalced Carmelites. Reputed to be one of the most educated and virtuous women of her time, Eleonore took part in the political affairs during the reign of her husband and sons, especially regarding court revenue and foreign relationships. She served as regent for a few months in 1711, period in which she signed the Treaty of Szatmár, which recognized the rights of her descendants to the Hungarian throne.

Maria Amalia of Austria was Holy Roman empress, queen of Bohemia, and electress of Bavaria among many other titles as the spouse of Emperor Charles VII. By birth, she was an archduchess of Austria as the daughter of Emperor Joseph I. One of her children was Maximilian III Joseph, Elector of Bavaria.

Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel was Princess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Holy Roman Empress, German Queen, Queen of Bohemia and Hungary; and Archduchess of Austria by her marriage to Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor. She was renowned for her delicate beauty and also for being the mother of Empress Maria Theresa. She was the longest serving Holy Roman Empress.

The Mutual Pact of Succession was a succession device secretly signed by archdukes Joseph and Charles of Austria, the future emperors of the Holy Roman Empire, in 1703.

The Pragmatic Army was an army which served during the War of the Austrian Succession. It was formed in 1743 by George II, who was both King of Great Britain and Elector of Hanover, and consisted of a mixture of British, Hanoverian, and Austrian forces. It was designed to uphold the Pragmatic Sanction in support of George's ally Maria Theresa of Austria and took its name from this.

The Article 7 of the Sabor of 1712, better known as the Pragmatic Sanction of 1712 or the Croatian Pragmatic Sanction, was a decision of the Croatian Parliament (Sabor) to accept that a Habsburg princess could become hereditary Queen of Croatia. It was passed against the will of the Diet of Hungary, despite the Kingdom of Croatia's centuries-long association with the Kingdom of Hungary. The resulting strife with the Hungarian officials ended with the legal recognition of the Croatian Parliament's sole jurisdiction over internal Croatian affairs. The Pragmatic Sanction is thus considered one of the most historically important decisions of the Croatian Parliament, and is recalled in the preamble of the Constitution of Croatia.

The Erblande of the House of Habsburg formed the Alpine heartland of the Habsburg monarchy. They were the hereditary possessions of the Habsburgs within the Holy Roman Empire from before 1526. The Erblande were not all unified under the head of the dynasty prior to the 17th century. They were divided into several groupings: the Archduchy of Austria, Inner Austria, the County of Tyrol, and Further Austria.

The Treaty of Nymphenburg was a treaty between Bavaria and Spain that was concluded on May 28, 1741 at the Nymphenburg Palace in Munich. It was the first formal pact of a series of French-sponsored alliances against the Habsburg Monarch, Maria Theresa. Through the agreement, the Bavarian Elector Charles Albert gained the support of King Philip V of Spain to become the next Holy Roman Emperor against the claims of the Habsburgs. The treaty was brokered by Marshal Belleisle under the authority of Louis XV of France. As part of the negotiations, the French agreed to materially support Charles Albert's claims. The treaty signaled the expansion of the First Silesian War, which started as a local war between Prussia and the Habsburg Monarchy, into the War of the Austrian Succession, a pan-European conflict.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Sugar 1994, p. 144.

- ↑ Ingrao 2000, p. 134.

- 1 2 3 4 Sugar 1994, p. 145.

- ↑ Sugar 1994, p. 245.

- ↑ Sugar 1994, p. 252.