Working memory is a cognitive system with a limited capacity that can hold information temporarily. It is important for reasoning and the guidance of decision-making and behavior. Working memory is often used synonymously with short-term memory, but some theorists consider the two forms of memory distinct, assuming that working memory allows for the manipulation of stored information, whereas short-term memory only refers to the short-term storage of information. Working memory is a theoretical concept central to cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and neuroscience.

In psychology, theory of mind refers to the capacity to understand other people by ascribing mental states to them. A theory of mind includes the knowledge that others' beliefs, desires, intentions, emotions, and thoughts may be different from one's own. Possessing a functional theory of mind is crucial for success in everyday human social interactions. People utilise a theory of mind when analyzing, judging, and inferring others' behaviors. The discovery and development of theory of mind primarily came from studies done with animals and infants. Factors including drug and alcohol consumption, language development, cognitive delays, age, and culture can affect a person's capacity to display theory of mind. Having a theory of mind is similar to but not identical with having the capacity for empathy or sympathy.

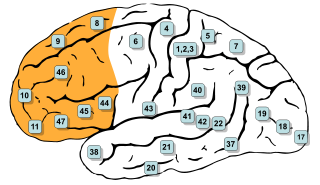

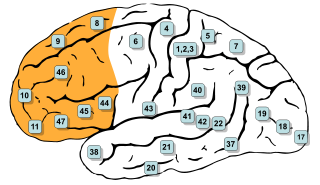

Brodmann area 10 is the anterior-most portion of the prefrontal cortex in the human brain. BA10 was originally defined broadly in terms of its cytoarchitectonic traits as they were observed in the brains of cadavers, but because modern functional imaging cannot precisely identify these boundaries, the terms anterior prefrontal cortex, rostral prefrontal cortex and frontopolar prefrontal cortex are used to refer to the area in the most anterior part of the frontal cortex that approximately covers BA10—simply to emphasize the fact that BA10 does not include all parts of the prefrontal cortex.

Pyramidal cells, or pyramidal neurons, are a type of multipolar neuron found in areas of the brain including the cerebral cortex, the hippocampus, and the amygdala. Pyramidal cells are the primary excitation units of the mammalian prefrontal cortex and the corticospinal tract. Pyramidal neurons are also one of two cell types where the characteristic sign, Negri bodies, are found in post-mortem rabies infection. Pyramidal neurons were first discovered and studied by Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Since then, studies on pyramidal neurons have focused on topics ranging from neuroplasticity to cognition.

The consciousness and binding problem is the problem of how objects, background and abstract or emotional features are combined into a single experience.

A gamma wave or gamma rhythm is a pattern of neural oscillation in humans with a frequency between 25 and 140 Hz, the 40 Hz point being of particular interest. Gamma rhythms are correlated with large-scale brain network activity and cognitive phenomena such as working memory, attention, and perceptual grouping, and can be increased in amplitude via meditation or neurostimulation. Altered gamma activity has been observed in many mood and cognitive disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, epilepsy, and schizophrenia.

In mammalian brain anatomy, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) covers the front part of the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex. The PFC contains the Brodmann areas BA8, BA9, BA10, BA11, BA12, BA13, BA14, BA24, BA25, BA32, BA44, BA45, BA46, and BA47.

Neural oscillations, or brainwaves, are rhythmic or repetitive patterns of neural activity in the central nervous system. Neural tissue can generate oscillatory activity in many ways, driven either by mechanisms within individual neurons or by interactions between neurons. In individual neurons, oscillations can appear either as oscillations in membrane potential or as rhythmic patterns of action potentials, which then produce oscillatory activation of post-synaptic neurons. At the level of neural ensembles, synchronized activity of large numbers of neurons can give rise to macroscopic oscillations, which can be observed in an electroencephalogram. Oscillatory activity in groups of neurons generally arises from feedback connections between the neurons that result in the synchronization of their firing patterns. The interaction between neurons can give rise to oscillations at a different frequency than the firing frequency of individual neurons. A well-known example of macroscopic neural oscillations is alpha activity.

A neuronal ensemble is a population of nervous system cells involved in a particular neural computation.

Neural binding is the neuroscientific aspect of what is commonly known as the binding problem: the interdisciplinary difficulty of creating a comprehensive and verifiable model for the unity of consciousness. "Binding" refers to the integration of highly diverse neural information in the forming of one's cohesive experience. The neural binding hypothesis states that neural signals are paired through synchronized oscillations of neuronal activity that combine and recombine to allow for a wide variety of responses to context-dependent stimuli. These dynamic neural networks are thought to account for the flexibility and nuanced response of the brain to various situations. The coupling of these networks is transient, on the order of milliseconds, and allows for rapid activity.

In cognitive science and neuropsychology, executive functions are a set of cognitive processes that are necessary for the cognitive control of behavior: selecting and successfully monitoring behaviors that facilitate the attainment of chosen goals. Executive functions include basic cognitive processes such as attentional control, cognitive inhibition, inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. Higher-order executive functions require the simultaneous use of multiple basic executive functions and include planning and fluid intelligence.

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) is a part of the prefrontal cortex in the mammalian brain. The ventral medial prefrontal is located in the frontal lobe at the bottom of the cerebral hemispheres and is implicated in the processing of risk and fear, as it is critical in the regulation of amygdala activity in humans. It also plays a role in the inhibition of emotional responses, and in the process of decision-making and self-control. It is also involved in the cognitive evaluation of morality.

The concept of motor cognition grasps the notion that cognition is embodied in action, and that the motor system participates in what is usually considered as mental processing, including those involved in social interaction. The fundamental unit of the motor cognition paradigm is action, defined as the movements produced to satisfy an intention towards a specific motor goal, or in reaction to a meaningful event in the physical and social environments. Motor cognition takes into account the preparation and production of actions, as well as the processes involved in recognizing, predicting, mimicking, and understanding the behavior of other people. This paradigm has received a great deal of attention and empirical support in recent years from a variety of research domains including embodied cognition, developmental psychology, cognitive neuroscience, and social psychology.

Visual object recognition refers to the ability to identify the objects in view based on visual input. One important signature of visual object recognition is "object invariance", or the ability to identify objects across changes in the detailed context in which objects are viewed, including changes in illumination, object pose, and background context.

The dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC or DMPFC is a section of the prefrontal cortex in some species' brain anatomy. It includes portions of Brodmann areas BA8, BA9, BA10, BA24 and BA32, although some authors identify it specifically with BA8 and BA9. Some notable sub-components include the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, the prelimbic cortex, and the infralimbic cortex.

Joni Wallis is a cognitive neurophysiologist and Professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of California, Berkeley.

Social cognitive neuroscience is the scientific study of the biological processes underpinning social cognition. Specifically, it uses the tools of neuroscience to study "the mental mechanisms that create, frame, regulate, and respond to our experience of the social world". Social cognitive neuroscience uses the epistemological foundations of cognitive neuroscience, and is closely related to social neuroscience. Social cognitive neuroscience employs human neuroimaging, typically using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Human brain stimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct-current stimulation are also used. In nonhuman animals, direct electrophysiological recordings and electrical stimulation of single cells and neuronal populations are utilized for investigating lower-level social cognitive processes.

The term posterior cortical hot zone was coined by Christof Koch and colleagues to describe the part of the neocortex closely associated with the minimal neural substrate essential for conscious perception. The posterior cortical hot zone includes sensory cortical areas in the parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes. It is the “sensory” cortex, much as the frontal cortex is the “action” cortex.

Prefrontal analysis (PFA) is a type of active constructive imagination that allows humans to mentally reduce an object into parts. For example, humans can recall a kettle and then mentally break a handle. The imaginary kettle with the broken handle, a horse without the tail, or a cow without the ear are novel objects since they were never before observed physically. The process of generating these objects in the mind is the process of image decomposition or analysis, as opposed to Prefrontal Synthesis that involves combining two or more objects together.

Hyperphantasia is the condition of having extremely vivid mental imagery. It is the opposite condition to aphantasia, where mental visual imagery is not present. The experience of hyperphantasia is more common than aphantasia and has been described as being "as vivid as real seeing". Hyperphantasia constitutes all five senses within vivid mental imagery, although literature on the subject is dominated by "visual" mental imagery research, with a lack of research on the other four senses.