Related Research Articles

Genre is any style or form of communication in any mode with socially agreed-upon conventions developed over time. In popular usage, it normally describes a category of literature, music, or other forms of art or entertainment, based on some set of stylistic criteria. Often, works fit into multiple genres by way of borrowing and recombining these conventions. Stand-alone texts, works, or pieces of communication may have individual styles, but genres are amalgams of these texts based on agreed-upon or socially inferred conventions. Some genres may have rigid, strictly adhered-to guidelines, while others may show great flexibility. The proper use of a specific genre is important for a successful transfer of information (media-adequacy).

A genre of arts criticism, literary criticism or literary studies is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical analysis of literature's goals and methods. Although the two activities are closely related, literary critics are not always, and have not always been, theorists.

Diegesis is a style of fiction storytelling in which a participating narrator offers an on-site, often interior, view of the scene to the reader, viewer, or listener by subjectively describing the actions and, in some cases, thoughts, of one or more characters. Diegetic events are those experienced by both the characters within a piece and the audience, while non-diegetic elements of a story make up the "fourth wall" separating the characters from the audience. Diegesis in music describes a character's ability to hear the music presented for the audience, in the context of musical theatre or film scoring.

Aristotle's Poetics is the earliest surviving work of Greek dramatic theory and the first extant philosophical treatise to focus on literary theory. In this text, Aristotle offers an account of ποιητική, which refers to poetry, and more literally, "the poetic art", deriving from the term for "poet; author; maker", ποιητής. Aristotle divides the art of poetry into verse drama, lyric poetry, and epic. The genres all share the function of mimesis, or imitation of life, but differ in three ways that Aristotle describes:

- There are differences in music rhythm, harmony, meter, and melody.

- There is a difference of goodness in the characters.

- A difference exists in how the narrative is presented: telling a story or acting it out.

Erich Auerbach was a German philologist and comparative scholar and critic of literature. His best-known work is Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, a history of representation in Western literature from ancient to modern times frequently cited as a classic in the study of realism in literature. Along with Leo Spitzer, Auerbach is widely recognized as one of the foundational figures of comparative literature.

Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays is a book by Canadian literary critic and theorist Northrop Frye that attempts to formulate an overall view of the scope, theory, principles, and techniques of literary criticism derived exclusively from literature. Frye consciously omits all specific and practical criticism, instead offering classically inspired theories of modes, symbols, myths and genres, in what he termed "an interconnected group of suggestions." The literary approach proposed by Frye in Anatomy was highly influential in the decades before deconstructivist criticism and other expressions of postmodernism came to prominence in American academia circa 1980s.

Jacopo Mazzoni was an Italian philosopher, a professor in Pisa, and friend of Galileo Galilei. His first name is sometimes reported as Giacomo.

René Noël Théophile Girard was a French historian, literary critic, and philosopher of social science whose work belongs to the tradition of philosophical anthropology. Girard was the author of nearly thirty books, with his writings spanning many academic domains. Although the reception of his work is different in each of these areas, there is a growing body of secondary literature on his work and his influence on disciplines such as literary criticism, critical theory, anthropology, theology, mythology, sociology, economics, cultural studies, and philosophy.

Francis Fergusson (1904–1986) was a Harvard and Oxford-educated teacher and critic, a theorist of drama and mythology who wrote The Idea of a Theater, a book about drama. He contributed an introductory essay to S. H. Butcher’s 1961 translation of Aristotle’s Poetics. His other works include Dante's Drama of the Mind: A Modern Reading of the Purgatorio, which includes his translations of many passages. In The Rarer Action, a volume in tribute to Francis Fergusson, the critic Allen Tate wrote: "The Idea of a Theater is a work comparable in range and depth with Eric Auerbach's Mimesis. There is no other work by an American critic of which this can be said."

Poetics is the study or theory of poetry, specifically the study or theory of device, structure, form, type, and effect with regards to poetry, though usage of the term can also refer to literature broadly. Poetics is distinguished from hermeneutics by its focus on the synthesis of non-semantic elements in a text rather than its semantic interpretation. Most literary criticism combines poetics and hermeneutics in a single analysis; however, one or the other may predominate given the text and the aims of the one doing the reading.

Verisimilitude is the "lifelikeness" or believability of a work of fiction. The word comes from Latin: verum meaning truth and similis meaning similar. Language philosopher Steve Neale distinguishes between two types: cultural verisimilitude, meaning plausibility of the fictional work within the cultural and/or historical context of the real world, outside of the work; and generic verisimilitude, meaning plausibility of a fictional work within the bounds of its own genre.

Gerald Frank Else was a distinguished American classicist. He was professor of Greek and Latin at University of Michigan and University of Iowa. Else is substantially credited with the refinement of Aristotelian scholarship in aesthetics in the 20th century to expand the reading of catharsis alone to include the aesthetic triad of mimesis, hamartia, and catharsis as all essentially linked to each other.

An Apology for Poetry is a work of literary criticism by Elizabethan poet Philip Sidney. It was written in approximately 1580 and first published in 1595, after his death.

In philosophy, lexis is a complete group of words in a language, vocabulary, the total set of all words in a language, and all words that have meaning or a function in grammar.

Dennis Ronald MacDonald is the John Wesley Professor of New Testament and Christian Origins at the Claremont School of Theology in California. MacDonald proposes a theory wherein the earliest books of the New Testament were responses to the Homeric Epics, including the Gospel of Mark and the Acts of the Apostles. The methodology he pioneered is called Mimesis Criticism. If his theories are correct then "nearly everything written on [the] early Christian narrative is flawed." According to him, modern biblical scholarship has failed to recognize the impact of Homeric Poetry.

Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature is a book of literary criticism by Erich Auerbach, and his most well known work. It was written in German between 1942 and 1945, while Auerbach was teaching in Istanbul, Turkey, where he fled after being ousted from his professorship in Romance Philology at the University of Marburg by the Nazis in 1935, it was first published in Switzerland in 1946 by A. Francke Verlag, with an English translation by Princeton University Press following in 1953, since when it has remained in print.

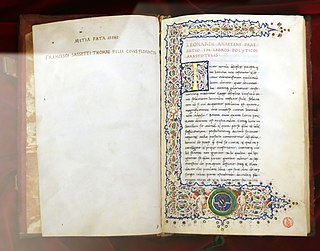

Dionysian imitatio is the influential literary method of imitation as formulated by Greek author Dionysius of Halicarnassus in the first century BCE, which conceived it as the rhetorical practice of emulating, adapting, reworking and enriching a source text by an earlier author. It is a departure from the concept of mimesis which only is concerned with "imitation of nature" instead of the "imitation of other authors."

Mimesis criticism is a method of interpreting texts in relation to their literary or cultural models. Mimesis, or imitation (imitatio), was a widely used rhetorical tool in antiquity up until the 18th century's romantic emphasis on originality. Mimesis criticism looks to identify intertextual relationships between two texts that go beyond simple echoes, allusions, citations, or redactions. The effects of imitation are usually manifested in the later text by means of distinct characterization, motifs, and/or plot structure.

Metaphysical concepts relate to the ideas of transcendent and universal elements that surpass the human interactions. They aim to explore notions that humans have yet to comprehend, or have merely touched on in order to provide an understanding of what lies beyond the physical world. Aesthetics aims to explore questions relating to the natural world, beauty and art, and the intertwining of each. Therefore, in conjunction with metaphysical concepts, these two branches of philosophy explore the transformative and distinctiveness of art and what distinguishes something as art. These ideas highly conflicted with modern scientific knowledge as they were based on theories and concepts in comparison to reliable experiments that resulted in tangible or viewable proof. In relation to naturalism many philosophers such as John Dewey, Ernest Nagel and Sidney Hook are compelled to believe that only what is seen and touched or scientifically proven can be true, and in saying so, can be meaningful to humans.

The mimetic theory of desire, an explanation of human behavior and culture, originated with the French historian, literary critic, and philosopher of social science René Girard (1923–2015). The name of the theory derives from the philosophical concept mimesis, which carries a wide range of meanings. In mimetic theory, mimesis refers to human desire, which Girard thought was not linear but the product of a mimetic process in which people imitate models who endow objects with value. Girard called this phenomenon "mimetic desire", and described mimetic desire as the foundation of his theory:

"Man is the creature who does not know what to desire, and he turns to others in order to make up his mind. We desire what others desire because we imitate their desires."

References

Classical sources

- ↑ Plato, Ion , 532c

- ↑ Plato, Ion , 540c

- ↑ Plato, Ion , 535b

- ↑ Plato, Republic, Book II, translated by B. Jowett.

- 1 2 3 Plato, Republic, Book X, translated by B. Jowett.

- ↑ Plato, The Republic, Book III, translated by B. Jowett. (Also available via Project Gutenberg):

You are aware, I suppose, that all mythology and poetry is a narration of events, either past, present, or to come? / Certainly, he replied.

And narration may be either simple narration, or imitation, or a union of the two? / [...] / And this assimilation of himself to another, either by the use of voice or gesture, is the imitation of the person whose character he assumes? / Of course. / Then in this case the narrative of the poet may be said to proceed by way of imitation? / Very true. / Or, if the poet everywhere appears and never conceals himself, then again, the imitation is dropped, and his poetry becomes simple narration. - ↑ Plato, 360 BC, The Republic, Book III, translated by B. Jowett. (Also available via Project Gutenberg).

- ↑ Aristotle, Poetics § I

- ↑ Aristotle, Poetics § III

Citations

- ↑ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- ↑ Gebauer and Wulf (1992, 1).

- ↑ Halliwell, Stephen. "'The Shifting Problems of Mimesis in Plato' [Author's MS] in J. Pfefferkorn & A. Spinelli (eds.) Platonic Mimesis Revisited (Academia Verlag, 2021)".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Auerbach, Erich. 1953. Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature . Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 069111336X.

- ↑ Aristotle (1968). Poetics. D. W. Lucas. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198141750. OCLC 3354067.

- ↑ Benjamin, Walter (1970). "On the Mimetic Faculty". Illuminations. London: Cape. ISBN 0224618253. OCLC 10931256.

- ↑ Horkheimer, Max (2002). Dialectic of enlightenment : philosophical fragments. Theodor W. Adorno, Gunzelin Schmid Noerr. Stanford, California. ISBN 978-0804788090. OCLC 919087055.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Taussig, Michael T. (1993). Mimesis and alterity : a particular history of the senses. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415906865. OCLC 26719038.

- ↑ Wilson, Kirt (2003). "The Racial Politics of Imitation in the Nineteenth Century". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 89 (2): 89–108. doi:10.1080/00335630308178. S2CID 144657276.

- ↑ Davis (1993, 3).

- ↑ See also, Pfister (1977, pp. 2–3); and Elam (1980):

"classical narrative is always oriented towards an explicit there and then, towards an imaginary 'elsewhere' set in the past and which has to be evoked for the reader through predication and description. Dramatic worlds, on the other hand, are presented to the spectator as 'hypothetically actual' constructs, since they are 'seen' in progress 'here and now' without narratorial mediation. [...] This is not merely a technical distinction but constitutes, rather, one of the cardinal principles of a poetics of the drama as opposed to one of narrative fiction. The distinction is, indeed, implicit in Aristotle's differentiation of representational modes, namely diegesis (narrative description) versus mimesis (direct imitation)." (pp. 110–111).

- ↑ Giner-Sorolla, Roger (April 2006). "Crimes Against Mimesis". Archived from the original on 19 June 2005. Retrieved 17 December 2006. This is a reformatted version of a set of articles originally posted to Usenet:

- Giner-Sorolla, Roger (11 April 2006). "Crimes Against Mimesis, Part 1" . Retrieved 17 December 2006.

- Giner-Sorolla, Roger (18 April 2006). "Crimes Against Mimesis, Part 2" . Retrieved 17 December 2006.

- Giner-Sorolla, Roger (25 April 2006). "Crimes Against Mimesis, Part 3" . Retrieved 17 December 2006.

- Giner-Sorolla, Roger (29 April 2006). "Crimes Against Mimesis, Part 4" . Retrieved 17 December 2006.

- 1 2 3 Ruthven (1979) pp. 103–104

- ↑ Jansen (2008)

- ↑ Coleridge, Samuel T. [1817] 1983. Biographia Literaria, vol. 1, edited by J. Engell and W. J. Bate. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691098743. p. 72.

- ↑ Auerbach, Erich. 1953. Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature . Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11336-X.

- 1 2 Benjamin, Walter (1986). Reflections : essays, aphorisms, autobiographical writing. Peter Demetz. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 333–335. ISBN 080520802X. OCLC 12805048.

- ↑ See .

- ↑ Taussig, 1993, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Girard, René (1987). Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World. Stanford University Press. pp. 7, 26, 307.

- ↑ Calasso, Roberto (2019). The unnamable present. Richard Dixon. New York. pp. 137–139. ISBN 978-0374279479. OCLC 1036096585.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Goebbels, Joseph (1941). "Mimicry". research.calvin.edu. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ↑ Adorno, Theodor (1944). Dialectic of Enlightenment. Verso. pp. 9–20 et al. ISBN 1784786802. OCLC 957655599.

- ↑ Benjamin, Walter (1968). Illuminations. Hannah Arendt. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 141–147, 217–265. ISBN 0-8052-0241-2. OCLC 12947710.

- ↑ "The Celestial Hunter by Roberto Calasso review – the sacrificial society". the Guardian. 9 May 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ↑ Calasso, Roberto (2020). The celestial hunter. Richard Dixon. New York. pp. 3–28, 97–156. ISBN 978-0374120061. OCLC 1102184868.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ See .

Bibliography

- Auerbach, Erich . 1953. Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature . Princeton: Princeton UP. ISBN 069111336X.

- Coleridge, Samuel T. 1983. Biographia Literaria, vol. 1, edited by J. Engell and W. J. Bate. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP. ISBN 0691098743.

- Davis, Michael. 1999. The Poetry of Philosophy: On Aristotle's Poetics . South Bend, IN: St Augustine's P. ISBN 1890318620.

- Elam, Keir. 1980. The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama , New Accents series. London: Methuen. ISBN 0416720609.

- Esposito, Mariangela (2023). The Realm of Mimesis in Plato: Orality, Writing, and the Ontology of the Image. Leiden; Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004533110.

- Gebauer, Gunter, and Christoph Wulf. [1992] 1995. Mimesis: Culture—Art—Society, translated by D. Reneau. Berkeley, CA: U of California Press. ISBN 0520084594.

- Girard, René. 2008. Mimesis and Theory: Essays on Literature and Criticism, 1953–2005, edited by R. Doran. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804755801.

- Halliwell, Stephen. 2002. The Aesthetics of Mimesis. Ancient Texts and Modern Problems . Princeton. ISBN 0691092583.

- Kaufmann, Walter . 1992. Tragedy and Philosophy . Princeton: Princeton UP. ISBN 0691020051.

- Lacoue-Labarthe, Philippe. 1989. Typography: Mimesis, Philosophy, Politics, edited by C. Fynsk. Cambridge: Harvard UP. ISBN 978-0804732826.

- Lawtoo, Nidesh. 2013. The Phantom of the Ego: Modernism and the Mimetic Unconscious. East Lansing: Michigan State UP. ISBN 978-1611860962.

- Lawtoo, Nidesh. 2022. Homo Mimeticus: A New Theory of Imitation Leuven: Leuven UP. ISBN 978-9462703469.

- Miller, Gregg Daniel. 2011. Mimesis and Reason: Habermas's Political Philosophy. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-1438437408

- Pfister, Manfred. [1977] 1988. The Theory and Analysis of Drama , translated by J. Halliday, European Studies in English Literature series. Cambridige: Cambridge UP. ISBN 052142383X.

- Potolsky, Matthew. 2006. Mimesis. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415700302.

- Prang, Christoph. 2010. "Semiomimesis: The influence of semiotics on the creation of literary texts. Peter Bichsel's Ein Tisch ist ein Tisch and Joseph Roth's Hotel Savoy." Semiotica (182):375–396.

- Sen, R. K. 1966. Aesthetic Enjoyment: Its Background in Philosophy and Medicine. Calcutta: University of Calcutta.

- —— 2001. Mimesis. Calcutta: Syamaprasad College.

- Sörbom, Göran. 1966. Mimesis and Art . Uppsala.

- Snow, Kim, Hugh Crethar, Patricia Robey, and John Carlson. 2005. "Theories of Family Therapy (Part 1)." As cited in "Family Therapy Review: Preparing for Comprehensive Licensing Examination." 2005. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0805843124.

- Tatarkiewicz, Władysław . 1980. A History of Six Ideas: An Essay in Aesthetics , translated by C. Kasparek . The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 9024722330.

- Taussig, Michael . 1993. Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses . London: Routledge. ISBN 0415906865.

- Tsitsiridis, Stavros. 2005. "Mimesis and Understanding. An Interpretation of Aristotle's 'Poetics' 4.1448b4–19." Classical Quarterly (55):435–446.