The Gospel of Luke tells of the origins, birth, ministry, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ. Together with the Acts of the Apostles, it makes up a two-volume work which scholars call Luke–Acts, accounting for 27.5% of the New Testament. The combined work divides the history of first-century Christianity into three stages, with the gospel making up the first two of these – the life of Jesus the Messiah from his birth to the beginning of his mission in the meeting with John the Baptist, followed by his ministry with events such as the Sermon on the Plain and its Beatitudes, and his Passion, death, and resurrection.

Homer was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the most revered and influential authors in history.

In Greek mythology, Elpenor, also spelled Elpinor, was the youngest comrade of Odysseus. While on the island of Circe, he became drunk and decided to spend the night on the roof. In the morning he slipped on the ladder, fell, and broke his neck, dying instantly.

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus was a Roman educator and rhetorician born in Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quintilian, although the alternate spellings of Quintillian and Quinctilian are occasionally seen, the latter in older texts.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary style was atticistic – imitating Classical Attic Greek in its prime.

Mimesis is a term used in literary criticism and philosophy that carries a wide range of meanings, including imitatio, imitation, nonsensuous similarity, receptivity, representation, mimicry, the act of expression, the act of resembling, and the presentation of the self.

Aristotle's Poetics is the earliest surviving work of Greek dramatic theory and the first extant philosophical treatise to focus on literary theory. In this text Aristotle offers an account of ποιητική, which refers to poetry and more literally "the poetic art," deriving from the term for "poet; author; maker," ποιητής. Aristotle divides the art of poetry into verse drama, lyric poetry, and epic. The genres all share the function of mimesis, or imitation of life, but differ in three ways that Aristotle describes:

- Differences in music rhythm, harmony, meter, and melody.

- Difference of goodness in the characters.

- Difference in how the narrative is presented: telling a story or acting it out.

Imitation of God is the religious precept of Man finding salvation by attempting to realize his concept of supreme being. It is found in ancient Greek philosophy and several world religions. In some branches of Christianity, however, it plays a key role.

The study of Jesus in comparative mythology is the examination of the narratives of the life of Jesus in the Christian gospels, traditions and theology, as they relate to Christianity and other religions. Although the vast majority of New Testament scholars and historians of the ancient Near East agree that Jesus existed as a historical figure, most secular historians also agree that the gospels contain large quantities of ahistorical legendary details mixed in with historical information about Jesus's life. The Synoptic Gospels of Mark, Matthew, and Luke are heavily shaped by Jewish tradition, with the Gospel of Matthew deliberately portraying Jesus as a "new Moses". Although it is highly unlikely that the authors of the Synoptic Gospels directly based any of their accounts on pagan mythology, it is possible that they may have subtly shaped their accounts of Jesus's healing miracles to resemble familiar Greek stories about miracles associated with Asclepius, the god of healing and medicine. The birth narratives of Matthew and Luke are usually seen by secular historians as legends designed to fulfill Jewish expectations about the Messiah.

Homeric Greek is the form of the Greek language that was used in the Iliad, Odyssey, and Homeric Hymns. It is a literary dialect of Ancient Greek consisting mainly of Ionic, with some Aeolic forms, a few from Arcadocypriot, and a written form influenced by Attic. It was later named Epic Greek because it was used as the language of epic poetry, typically in dactylic hexameter, by poets such as Hesiod and Theognis of Megara. Compositions in Epic Greek may date from as late as the 5th century CE, and it only fell out of use by the end of classical antiquity.

The Homeric Question concerns the doubts and consequent debate over the identity of Homer, the authorship of the Iliad and Odyssey, and their historicity. The subject has its roots in classical antiquity and the scholarship of the Hellenistic period, but has flourished among Homeric scholars of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries.

"Odysseus' Scar" is the first chapter of Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, a collection of essays by German-Jewish philologist Erich Auerbach charting the development of representations of reality in literature. This first chapter examines the differences between two types of writing about reality embodied by Homer's Odyssey and the Old Testament. In the essay, Auerbach introduces his anti-rhetorical position, a position developed further in the companion essay "Fortunata" which compares the Roman tradition of Tacitus and Petronius with the New Testament, as anathema to a true representation of everyday life. Auerbach proceeds with this comparative approach until the triumph of Flaubert, Balzac and "modern realism".

Eutychus was a young man of Troas tended to by St. Paul. Eutychus fell asleep due to the long nature of the discourse Paul was giving, fell from a window out of the three-story building, and died. Paul then embraced him, insisting that he was not dead, and they carried him back upstairs alive; those gathered then had a meal and a long talk which lasted until dawn. This is related in the New Testament book of the Acts of the Apostles 20:7–12.

Dennis Ronald MacDonald is the John Wesley Professor of New Testament and Christian Origins at the Claremont School of Theology in California. MacDonald proposes a theory wherein the earliest books of the New Testament were responses to the Homeric Epics, including the Gospel of Mark and the Acts of the Apostles. The methodology he pioneered is called Mimesis Criticism. If his theories are correct then "nearly everything written on [the] early Christian narrative is flawed." According to him, modern biblical scholarship has failed to recognize the impact of Homeric Poetry.

Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature is a book of literary criticism by Erich Auerbach, and his most well known work. Written while Auerbach was teaching in Istanbul, Turkey, where he fled after being ousted from his professorship in Romance Philology at the University of Marburg by the Nazis in 1935, it was first published in 1946 by A. Francke Verlag.

The gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles make up a two-volume work which scholars call Luke–Acts. The author is not named in either volume. According to a Church tradition, first attested by Irenaeus, he was the Luke named as a companion of Paul in three of the Pauline letters, but "a critical consensus emphasizes the countless contradictions between the account in Acts and the authentic Pauline letters." The eclipse of the traditional attribution to Luke the companion of Paul has meant that an early date for the gospel is now rarely put forward. Most scholars date the composition of the combined work to around 80–90 AD, although some others suggest 90–110, and there is textual evidence that Luke–Acts was still being substantially revised well into the 2nd century.

Heraclitus was a grammarian and rhetorician, who wrote a Greek commentary on Homer which is still extant.

Dionysian imitatio is the influential literary method of imitation as formulated by Greek author Dionysius of Halicarnassus in the first century BCE, which conceived it as the rhetorical practice of emulating, adapting, reworking and enriching a source text by an earlier author. It is a departure from the concept of mimesis which only is concerned with "imitation of nature" instead of the "imitation of other authors."

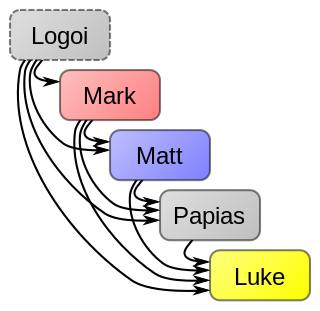

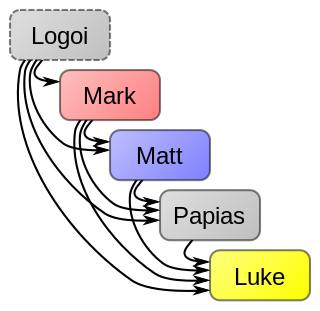

Advanced by Dennis R. MacDonald, the Q+/Papias hypothesis (Q+/PapH) offers an alternative solution to the synoptic problem. MacDonald prefers to call this expanded version of Q Logoi of Jesus, which is supposed to have been its original title.

On Training for Public Speaking is a short text written by Dio Chrysostom in the late first or early second century AD. The work takes the form of a letter to an anonymous man of affairs who has decided to train as a public speaker. It mostly consists of recommendations of authors for the recipient to read as examples of good style. The text is thus an important source on the formation of the Greek Classical canon in the early Roman empire.