Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus, commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and theologian, educationalist, satirist, and philosopher. Through his vast number of translations, books, essays, prayers and letters, he is considered one of the most influential thinkers of the Northern Renaissance and one of the major figures of Dutch and Western culture.

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse (trivium) along with grammar and logic/dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or writers use to inform, persuade, and motivate their audiences. Rhetoric also provides heuristics for understanding, discovering, and developing arguments for particular situations.

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus was a Roman educator and rhetorician born in Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quintilian, although the alternate spellings of Quintillian and Quinctilian are occasionally seen, the latter in older texts.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary style was atticistic – imitating Classical Attic Greek in its prime.

William Lily was an English classical grammarian and scholar. He was an author of the most widely used Latin grammar textbook in England and was the first high master of St Paul's School, London.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1512.

Polydore Vergil or Virgil, widely known as Polydore Vergil of Urbino, was an Italian humanist scholar, historian, priest and diplomat, who spent much of his life in England. He is particularly remembered for his works the Proverbiorum libellus (1498), a collection of Latin proverbs; De inventoribus rerum (1499), a history of discoveries and origins; and the Anglica Historia, an influential history of England. He has been dubbed the "Father of English History".

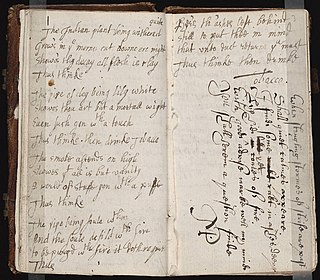

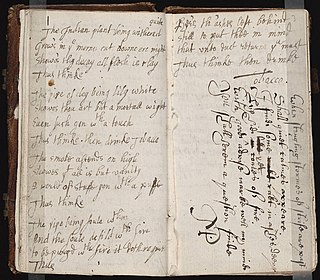

Commonplace books are a way to compile knowledge, usually by writing information into books. They have been kept from antiquity, and were kept particularly during the Renaissance and in the nineteenth century. Such books are similar to scrapbooks filled with items of many kinds: notes, proverbs, adages, aphorisms, maxims, quotes, letters, poems, tables of weights and measures, prayers, legal formulas, and recipes.

Robert Whittington was an English grammarian. He was a pupil at Magdalen College School, Oxford, where he probably studied under the grammarian John Stanbridge.

The Education of a Christian Prince is a Renaissance "how-to" book for princes, by Desiderius Erasmus, which advises the reader on how to be a good Christian prince. The book was dedicated to Prince Charles, who later became Habsburg Emperor Charles V.

Gasparino Barzizza was an Italian grammarian and teacher noted for introducing a new style of epistolary Latin inspired by the works of Cicero.

Ecclesiastes: On the Art of Preaching was a 1535 book by Desiderius Erasmus. One of the last major works he produced, Ecclesiastes focuses on the subject of effective preaching. Previously, Erasmus had written treatises on the Christian layperson, Christian prince, and Christian educator. Friends and admirers, including Bishop John Fisher suggested that Erasmus write on the office of the Christian priesthood. He began writing the text in 1523, finally completing and printing Ecclesiastes in 1535.

L'huomo di lettere difeso ed emendato by the Ferrarese Jesuit Daniello Bartoli (1608–1685) is a two-part treatise on the man of letters bringing together material he had assembled over twenty years since his entry in 1623 into the Society of Jesus as a brilliant student, a successful teacher of rhetoric and a celebrated preacher. His international literary success with this work led to his appointment in Rome as the official historiographer of the Society of Jesus and his monumental Istoria della Compagnia di Gesu (1650–1673).

Robert Sonkowsky was a professor emeritus of Classical and Near Eastern Studies at the University of Minnesota. He was an authority on Latin rhetoric and the pronunciation of Golden Age Latin. His bachelor's degree was from Lawrence College (1954), and his PhD from the University of North Carolina (1958). He was an Honorary Member of the Center for Chronobiology in the Mayo Building, Medical School.

Leonard Cox was an English humanist, author of the first book in English on rhetoric. He was a scholar of international reputation who found patronage in Poland, and was friend of Erasmus and Melanchthon. He was known to contemporaries as a grammarian, rhetorician, poet, and preacher, and was skilled in the modern as well as the classical languages.

The Rhetoric to Alexander is a treatise traditionally attributed to Aristotle. It is now generally believed to be the work of Anaximenes of Lampsacus.

In classical rhetoric, figures of speech are classified as one of the four fundamental rhetorical operations or quadripartita ratio: addition (adiectio), omission (detractio), permutation (immutatio) and transposition (transmutatio).

Dionysian imitatio is the influential literary method of imitation as formulated by Greek author Dionysius of Halicarnassus in the first century BCE, which conceived it as the rhetorical practice of emulating, adapting, reworking and enriching a source text by an earlier author. It is a departure from the concept of mimesis which only is concerned with "imitation of nature" instead of the "imitation of other authors."

Desiderius Erasmus was the most popular, most printed and arguably most influential author of the early Sixteenth Century, read in all nations in the West and frequently translated. By the 1530s, the writings of Erasmus accounted for 10 to 20 percent of all book sales in Europe. "Undoubtedly he was the most read author of his age."