Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse (trivium) along with grammar and logic/dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or writers use to inform, persuade, and motivate their audiences. Rhetoric also provides heuristics for understanding, discovering, and developing arguments for particular situations.

A sophist was a teacher in ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. Sophists specialized in one or more subject areas, such as philosophy, rhetoric, music, athletics and mathematics. They taught arete, "virtue" or "excellence", predominantly to young statesmen and nobility.

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus was a Roman educator and rhetorician born in Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quintilian, although the alternate spellings of Quintillian and Quinctilian are occasionally seen, the latter in older texts.

Dispositio is the system used for the organization of arguments in the context of Western classical rhetoric. The word is Latin, and can be translated as "organization" or "arrangement".

The Dialogus de oratoribus is a short work attributed to Tacitus, in dialogue form, on the art of rhetoric. Its date of composition is unknown, though its dedication to Lucius Fabius Justus places its publication around 102 AD.

Lucius Licinius Crassus was a Roman orator and statesman who was a Roman consul and censor and who is also one of the main speakers in Cicero's dramatic dialogue on the art of oratory De Oratore, set just before Crassus' death in 91 BC. He was considered the greatest orator of his day by his pupil Cicero.

Gilbert Austin (1753–1837) was an Irish educator, clergyman and author. Austin is best known for his 1806 book on chironomia, Chironomia, or a Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery. Heavily influenced by classical writers, Austin stressed the importance of voice and gesture to a successful oration.

Owing to its origin in ancient Greece and Rome, English rhetorical theory frequently employs Greek and Latin words as terms of art. This page explains commonly used rhetorical terms in alphabetical order. The brief definitions here are intended to serve as a quick reference rather than an in-depth discussion. For more information, click the terms.

De Oratore is a dialogue written by Cicero in 55 BC. It is set in 91 BC, when Lucius Licinius Crassus dies, just before the Social War and the civil war between Marius and Sulla, during which Marcus Antonius, the other great orator of this dialogue, dies. During this year, the author faces a difficult political situation: after his return from exile in Dyrrachium, his house was destroyed by the gangs of Clodius in a time when violence was common. This was intertwined with the street politics of Rome.

Institutio Oratoria is a twelve-volume textbook on the theory and practice of rhetoric by Roman rhetorician Quintilian. It was published around year 95 AD. The work deals also with the foundational education and development of the orator himself.

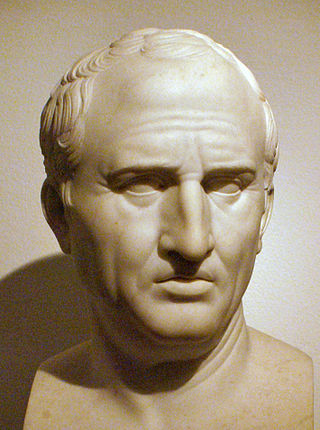

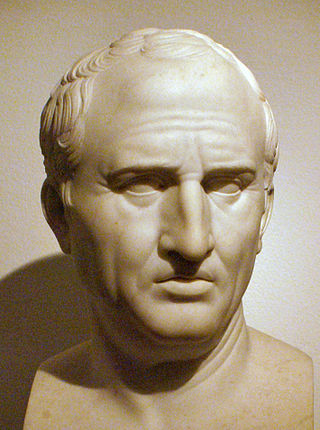

The writings of Marcus Tullius Cicero constitute one of the most renowned collections of historical and philosophical work in all of classical antiquity. Cicero was a Roman politician, lawyer, orator, political theorist, philosopher, and constitutionalist who lived during the years of 106–43 BC. He held the positions of Roman senator and Roman consul (chief-magistrate) and played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. He was extant during the rule of prominent Roman politicians, such as those of Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Marc Antony. Cicero is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.

De Oratore, Book III is the third part of De Oratore by Cicero. It describes the death of Lucius Licinius Crassus.

The gens Caepasia or Cepasia was an obscure plebeian family at Ancient Rome. It is known primarily from two brothers, Gaius and Lucius Caepasius, who obtained the quaestorship through their oratorical skill. Cicero describes them as contemporaries of Quintus Hortensius, and says that they were hard workers, although their rhetorical style was relatively simple. Several members of this gens are known from early Christian inscriptions at Rome, including a number of children.

De Optimo Genere Oratorum, "On the Best Kind of Orators", is a work from Marcus Tullius Cicero written in 46 BCE between two of his other works, Brutus and the Orator ad M. Brutum. Cicero attempts to explain why his view of oratorical style reflects true Atticism and is better than that of the Roman Atticists "who would confine the orator to the simplicity and artlessness of the early Attic orators."

In classical rhetoric, figures of speech are classified as one of the four fundamental rhetorical operations or quadripartita ratio: addition (adiectio), omission (detractio), permutation (immutatio) and transposition (transmutatio).

The Asiatic style or Asianism refers to an Ancient Greek rhetorical tendency that arose in the third century BC, which, although of minimal relevance at the time, briefly became an important point of reference in later debates about Roman oratory.

Orator was written by Marcus Tullius Cicero in the latter part of the year 46 BC. It is his last work on rhetoric, three years before his death. Describing rhetoric, Cicero addresses previous comments on the five canons of rhetoric: Inventio, Dispositio, Elocutio, Memoria, and Pronuntiatio. In this text, Cicero attempts to describe the perfect orator, in response to Marcus Junius Brutus’ request. Orator is the continuation of a debate between Brutus and Cicero, which originated in his text Brutus, written earlier in the same year.

In linguistics and literature, adnomination is a rhetorical device that involves the juxtaposed repetition of words with similar roots or speech sounds within a phrase or sentence. This technique serves to emphasize a particular concept or create a memorable rhythm captivating the audience's attention. It has been employed throughout history, from ancient orators to modern writers, demonstrating its enduring effectiveness in communication.

An orator is a person who speaks in public.

De Fato is a partially lost philosophical treatise written by the Roman orator Cicero in 44 BC. Only two-thirds of the work exists; the beginning and ending are missing. It takes the form of a dialogue, although it reads more like an exposition, whose interlocutors are Cicero and his friend Aulus Hirtius.