Zeno of Citium was a Hellenistic philosopher from Citium, Cyprus. He was the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy, which he taught in Athens from about 300 BC. Based on the moral ideas of the Cynics, Stoicism laid great emphasis on goodness and peace of mind gained from living a life of virtue in accordance with nature. It proved very popular, and flourished as one of the major schools of philosophy from the Hellenistic period through to the Roman era, and enjoyed revivals in the Renaissance as Neostoicism and in the current era as Modern Stoicism.

Chrysippus of Soli was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a native of Soli, Cilicia, but moved to Athens as a young man, where he became a pupil of the Stoic philosopher Cleanthes. When Cleanthes died, around 230 BC, Chrysippus became the third head of the Stoic school. A prolific writer, Chrysippus expanded the fundamental doctrines of Cleanthes' mentor Zeno of Citium, the founder and first head of the school, which earned him the title of the Second Founder of Stoicism.

An augur was a priest and official in the classical Roman world. His main role was the practice of augury, the interpretation of the will of the gods by studying events he observed within a predetermined sacred space (templum). The templum corresponded to the heavenly space above. The augur's decisions were based on what he personally saw or heard from within the templum; they included thunder, lightning and any accidental signs such as falling objects, but in particular, birdsigns; whether the birds he saw flew in groups or alone, what noises they made as they flew, the direction of flight, what kind of birds they were, how many there were, or how they fed. This practice was known as "taking the auspices". As circumstance did not always favour the convenient appearance of wild birds or weather phenomena, domesticated chickens kept for the purpose were sometimes released into the templum, where their behaviour, particularly how they fed, could be studied by the augur.

Aulus Hirtius was consul of the Roman Republic in 43 BC and a writer on military subjects. He was killed during his consulship in battle against Mark Antony at the Battle of Mutina.

Fatalism is a belief and philosophical doctrine which considers the entire universe as a deterministic system and stresses the subjugation of all events, actions, and behaviors to fate or destiny, which is commonly associated with the consequent attitude of resignation in the face of future events which are thought to be inevitable and outside of human control.

The lazy argument or idle argument is an attempt to undermine the philosophical doctrine of fatalism by demonstrating that, if everything that happens is determined by fate, it is futile to take any kind of action. Its basic form is that of a complex constructive dilemma.

Panaetius of Rhodes was an ancient Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a pupil of Diogenes of Babylon and Antipater of Tarsus in Athens, before moving to Rome where he did much to introduce Stoic doctrines to the city, thanks to the patronage of Scipio Aemilianus. After the death of Scipio in 129 BC, he returned to the Stoic school in Athens, and was its last undisputed scholarch. With Panaetius, Stoicism became much more eclectic. His most famous work was his On Duties, the principal source used by Cicero in his own work of the same name.

Zeno of Sidon was a Greek Epicurean philosopher from the Seleucid city of Sidon. His writings have not survived, but there are some epitomes of his lectures preserved among the writings of his pupil Philodemus.

Aristo of Chios, also spelled Ariston, was a Greek Stoic philosopher and colleague of Zeno of Citium. He outlined a system of Stoic philosophy that was, in many ways, closer to earlier Cynic philosophy. He rejected the logical and physical sides of philosophy endorsed by Zeno and emphasized ethics. Although agreeing with Zeno that Virtue was the supreme good, he rejected the idea that morally indifferent things such as health and wealth could be ranked according to whether they are naturally preferred. An important philosopher in his day, his views were eventually marginalized by Zeno's successors.

Clitomachus or Cleitomachus was a Greek philosopher, originally from Carthage, who came to Athens in 163/2 BC and studied philosophy under Carneades. He became head of the Academy around 127/6 BC. He was an Academic skeptic like his master. Nothing survives of his writings, which were dedicated to making known the views of Carneades, but Cicero made use of them for some of his works.

De Divinatione is a philosophical dialogue about ancient Roman divination written in 44 BC by Marcus Tullius Cicero.

Diodorus Cronus was a Greek philosopher and dialectician connected to the Megarian school. He was most notable for logic innovations, including his master argument formulated in response to Aristotle's discussion of future contingents.

Diogenes of Babylon was a Stoic philosopher. He was the head of the Stoic school in Athens, and he was one of three philosophers sent to Rome in 155 BC. He wrote many works, but none of his writings survived, except as quotations by later writers.

De Natura Deorum is a philosophical dialogue by Roman Academic Skeptic philosopher Cicero written in 45 BC. It is laid out in three books that discuss the theological views of the Hellenistic philosophies of Epicureanism, Stoicism, and Academic Skepticism.

Antipater of Tarsus was a Stoic philosopher. He was the pupil and successor of Diogenes of Babylon as leader of the Stoic school, and was the teacher of Panaetius. He wrote works on the gods and on divination, and in ethics he took a higher moral ground than that of his teacher Diogenes.

Quintus Lucilius Balbus was a Stoic philosopher and a pupil of Panaetius.

In logic, contingency is the feature of a statement making it neither necessary nor impossible. Contingency is a fundamental concept of modal logic. Modal logic concerns the manner, or mode, in which statements are true. Contingency is one of three basic modes alongside necessity and possibility. In modal logic, a contingent statement stands in the modal realm between what is necessary and what is impossible, never crossing into the territory of either status. Contingent and necessary statements form the complete set of possible statements. While this definition is widely accepted, the precise distinction between what is contingent and what is necessary has been challenged since antiquity.

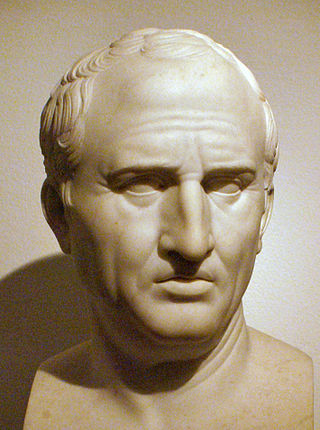

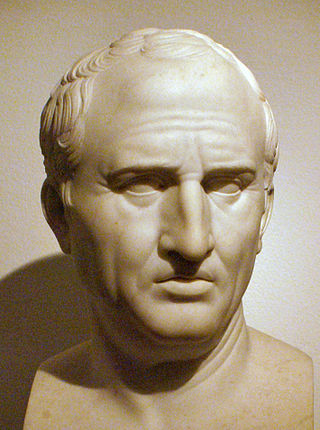

The writings of Marcus Tullius Cicero constitute one of the most renowned collections of historical and philosophical work in all of classical antiquity. Cicero was a Roman politician, lawyer, orator, political theorist, philosopher, and constitutionalist who lived during the years of 106–43 BC. He held the positions of Roman senator and Roman consul (chief-magistrate) and played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. He was extant during the rule of prominent Roman politicians, such as those of Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Marc Antony. Cicero is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.

In Classical mythology, Dolus (Deception) is a figure who appears in an Aesopic fable by the Roman fabulist Gaius Julius Phaedrus, where he is an apprentice of the Titan Prometheus. According to the Roman mythographer Hyginus, Dolus was the offspring of Aether and Terra (Earth), while Cicero has Dolus being the offspring of Aether and Dies (Day).

The Paradoxa Stoicorum is a work by the academic skeptic philosopher Cicero in which he attempts to explain six famous Stoic sayings that appear to go against common understanding: (1) virtue is the sole good; (2) virtue is the sole requisite for happiness; (3) all good deeds are equally virtuous and all bad deeds equally vicious; (4) all fools are mad; (5) only the wise are free, whereas all fools are enslaved; and (6) only the wise are rich.