A first-person narrative is a mode of storytelling in which a storyteller recounts events from their own point of view using the first person such as "I", "us", "our" and "ourselves". It may be narrated by a first-person protagonist, first-person re-teller, first-person witness, or first-person peripheral. A classic example of a first-person protagonist narrator is Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre (1847), in which the title character is also the narrator telling her own story, "I could not unlove him now, merely because I found that he had ceased to notice me".

Storytelling is the social and cultural activity of sharing stories, sometimes with improvisation, theatrics or embellishment. Every culture has its own stories or narratives, which are shared as a means of entertainment, education, cultural preservation or instilling moral values. Crucial elements of stories and storytelling include plot, characters and narrative point of view. The term "storytelling" can refer specifically to oral storytelling but also broadly to techniques used in other media to unfold or disclose the narrative of a story.

A narrative, story, or tale is any account of a series of related events or experiences, whether nonfictional or fictional. Narratives can be presented through a sequence of written or spoken words, through still or moving images, or through any combination of these. The word derives from the Latin verb narrare, which is derived from the adjective gnarus. Narration is a rhetorical mode of discourse, broadly defined, is one of four rhetorical modes of discourse. More narrowly defined, it is the fiction-writing mode in which a narrator communicates directly to an audience. The school of literary criticism known as Russian formalism has applied methods that are more often used to analyse narrative fiction, to non-fictional texts such as political speeches.

William Labov is an American linguist widely regarded as the founder of the discipline of variationist sociolinguistics. He has been described as "an enormously original and influential figure who has created much of the methodology" of sociolinguistics. He is a professor emeritus in the linguistics department of the University of Pennsylvania and pursues research in sociolinguistics, language change, and dialectology. He retired in 2015 but continues to publish research.

Diegesis is a style of fiction storytelling which presents an interior view of a world in which the narrator presents the actions of the characters to the readers or audience.

An unreliable narrator is a narrator whose credibility is compromised. They can be found in fiction and film, and range from children to mature characters. The term was coined in 1961 by Wayne C. Booth in The Rhetoric of Fiction. While unreliable narrators are almost by definition first-person narrators, arguments have been made for the existence of unreliable second- and third-person narrators, especially within the context of film and television, and sometimes also in literature.

Narration is the use of a written or spoken commentary to convey a story to an audience. Narration is conveyed by a narrator: a specific person, or unspecified literary voice, developed by the creator of the story to deliver information to the audience, particularly about the plot: the series of events. Narration is a required element of all written stories, presenting the story in its entirety. However, narration is merely optional in most other storytelling formats, such as films, plays, television shows, and video games, in which the story can be conveyed through other means, like dialogue between characters or visual action.

A frame story is a literary technique that serves as a companion piece to a story within a story, where an introductory or main narrative sets the stage either for a more emphasized second narrative or for a set of shorter stories. The frame story leads readers from a first story into one or more other stories within it. The frame story may also be used to inform readers about aspects of the secondary narrative(s) that may otherwise be hard to understand. This should not be confused with narrative structure.

Alias Grace is a historical fiction novel by Canadian writer Margaret Atwood. First published in 1996 by McClelland & Stewart, it won the Canadian Giller Prize and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize.

Haunted is a 2005 novel by Chuck Palahniuk. The plot is a frame story for a series of 23 short stories, most preceded by a free verse poem. Each story is followed by a chapter of the main narrative, is told by a character in main narrative, and ties back into the main story in some way. Typical of Palahniuk's work, the dominant motifs in Haunted are sexual deviance, sexual identity, desperation, social distastefulness, disease, murder, death, and existentialism.

Narrative inquiry or narrative analysis emerged as a discipline from within the broader field of qualitative research in the early 20th century, as evidence exists that this method was used in psychology and sociology. Narrative inquiry uses field texts, such as stories, autobiography, journals, field notes, letters, conversations, interviews, family stories, photos, and life experience, as the units of analysis to research and understand the way people create meaning in their lives as narratives.

An exemplum is a moral anecdote, brief or extended, real or fictitious, used to illustrate a point. The word is also used to express an action performed by another and used as an example or model.

Time's Arrow: or The Nature of the Offence (1991) is a novel by Martin Amis. It was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1991. It is notable partly because the events occur in a reverse chronology, with time passing in reverse and the main character becoming younger and younger during the novel.

Show, don't tell is a technique used in various kinds of texts to allow the reader to experience the story through actions, words, subtext, thoughts, senses, and feelings rather than through the author's exposition, summarization, and description. It avoids adjectives describing the author's analysis, but instead describes the scene in such a way that readers can draw their own conclusions. The technique applies equally to nonfiction and all forms of fiction, literature including haiku and Imagism poetry in particular, speech, movie making, and playwriting.

All Marketers Are Liars: The Power of Telling Authentic Stories in a Low Trust World (2005) is the seventh published book by Seth Godin, and the third in a series of books on 21st century marketing, following Purple Cow and Free Prize Inside.

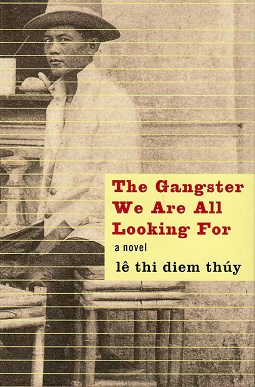

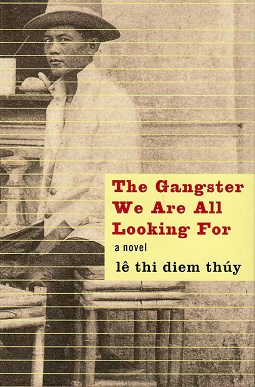

The Gangster We Are All Looking For is the first novel by Vietnamese-American author lê thi diem thúy, published in 2003. It was first published as a short piece in The Best American Essays of 1997 and was also awarded a Pushcart Prize “Special Mention.”

Alaska Native storytelling has been passed down through generations by means of oral presentation. The stories tell life lessons or serve as lessons in heritage. Many different aspects of Arctic life are incorporated into each story, mainly the various animals found in Alaska. Due to the decline in the number of speakers of native languages in Alaska and a change in lifestyle amongst many of the native peoples, oral storytelling has become less common. In recent years many of these stories have been written down, though many people argue that the telling of the story is just as important as the words within.

The theory of narrative identity postulates that individuals form an identity by integrating their life experiences into an internalized, evolving story of the self that provides the individual with a sense of unity and purpose in life. This life narrative integrates one's reconstructed past, perceived present, and imagined future. Furthermore, this narrative is a story – it has characters, episodes, imagery, a setting, plots, and themes and often follows the traditional model of a story, having a beginning, middle, and an end (denouement). Narrative identity is the focus of interdisciplinary research, with deep roots in psychology.

Personal narrative (PN) is a prose narrative relating personal experience usually told in first person; its content is nontraditional. "Personal" refers to a story from one's life or experiences. "Nontraditional" refers to literature that does not fit the typical criteria of a narrative.

Dominant narrative can be used to describe the lens in which history is told by the perspective of the dominant culture. This term has been described as an "invisible hand" that guides reality and perceived reality. Dominant narrative can refer to multiple aspects of life, such as history, politics, or different activist groups. Dominant culture is defined as the majority cultural practices of a society. Narrative can be defined as story telling, either true or imaginary. Pairing these two terms together create the notion of dominant narrative, that only the majority story is told and therefore heard. It is a common theme to hear or learn only about the dominant narrative as it comprises the perspective of the majority culture. Examples of dominant narrative can be seen throughout history. Dominant narrative can be defined and decided by the sociopolitical and socioeconomic setting someone lives his or her life in.