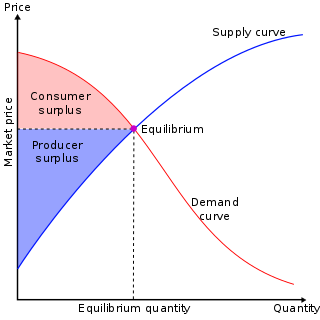

In mainstream economics, economic surplus, also known as total welfare or total social welfare or Marshallian surplus, is either of two related quantities:

In economics, an externality or external cost is an indirect cost or benefit to an uninvolved third party that arises as an effect of another party's activity. Externalities can be considered as unpriced goods involved in either consumer or producer market transactions. Air pollution from motor vehicles is one example. The cost of air pollution to society is not paid by either the producers or users of motorized transport to the rest of society. Water pollution from mills and factories is another example. All consumers are made worse off by pollution but are not compensated by the market for this damage. A positive externality is when an individual's consumption in a market increases the well-being of others, but the individual does not charge the third party for the benefit. The third party is essentially getting a free product. An example of this might be the apartment above a bakery receiving the benefit of enjoyment from smelling fresh pastries every morning. The people who live in the apartment do not compensate the bakery for this benefit.

In economics, a public good is a good that is both non-excludable and non-rivalrous. Use by one person neither prevents access by other people, nor does it reduce availability to others. Therefore, the good can be used simultaneously by more than one person. This is in contrast to a common good, such as wild fish stocks in the ocean, which is non-excludable but rivalrous to a certain degree. If too many fish were harvested, the stocks would deplete, limiting the access of fish for others. A public good must be valuable to more than one user, otherwise, its simultaneous availability to more than one person would be economically irrelevant.

Information goods are commodities that provide value to consumers as a result of the information it contains and refers to any good or service that can be digitalized. Examples of information goods includes books, journals, computer software, music and videos. Information goods can be copied, shared, resold or rented. Information goods are durable and thus, will not be destroyed through consumption. As information goods have distinct characteristics as they are experience goods, have returns to scale and are non-rivalrous, the laws of supply and demand that depend on the scarcity of products do not frequently apply to information goods. As a result, the buying and selling of information goods differs from ordinary goods. Information goods are goods whose unit production costs are negligible compared to their amortized development costs. Well-informed companies have development costs that increase with product quality, but their unit cost is zero. Once an information commodity has been developed, other units can be produced and distributed at almost zero cost. For example, allow downloads over the Internet. Conversely, for industrial goods, the unit cost of production and distribution usually dominates. Firms with an industrial advantage do not incur any development costs, but unit costs increase as product quality improves.

The theory of consumer choice is the branch of microeconomics that relates preferences to consumption expenditures and to consumer demand curves. It analyzes how consumers maximize the desirability of their consumption, by maximizing utility subject to a consumer budget constraint. Factors influencing consumers' evaluation of the utility of goods include: income level, cultural factors, product information and physio-psychological factors.

In economics, an inferior good is a good whose demand decreases when consumer income rises, unlike normal goods, for which the opposite is observed. Normal goods are those goods for which the demand rises as consumer income rises.

In economics and particularly in consumer choice theory, the income-consumption curve is a curve in a graph in which the quantities of two goods are plotted on the two axes; the curve is the locus of points showing the consumption bundles chosen at each of various levels of income.

In economics, goods are items that satisfy human wants and provide utility, for example, to a consumer making a purchase of a satisfying product. A common distinction is made between goods which are transferable, and services, which are not transferable.

In economics, a good is said to be rivalrous or a rival if its consumption by one consumer prevents simultaneous consumption by other consumers, or if consumption by one party reduces the ability of another party to consume it. A good is considered non-rivalrous or non-rival if, for any level of production, the cost of providing it to a marginal (additional) individual is zero. A good is "anti-rivalrous" and "inclusive" if each person benefits more when other people consume it.

Club goods are a type of good in economics, sometimes classified as a subtype of public goods that are excludable but non-rivalrous, at least until reaching a point where congestion occurs. Often these goods exhibit high excludability, but at the same time low rivalry in consumption. Thus, club goods have essentially zero marginal costs and are generally provided by what is commonly known as natural monopolies. Furthermore, club goods have artificial scarcity. Club theory is the area of economics that studies these goods. One of the most famous provisions was published by Buchanan in 1965 "An Economic Theory of Clubs," in which he addresses the question of how the size of the group influences the voluntary provision of a public good and more fundamentally provides a theoretical structure of communal or collective ownership-consumption arrangements.

In traditional usage, a global public good is a public good available on a more-or-less worldwide basis. There are many challenges to the traditional definition, which have far-reaching implications in the age of globalization.

Positional goods are goods valued only by how they are distributed among the population, not by how many of them there are available in total. The source of greater worth of positional goods is their desirability as a status symbol, which usually results in them greatly exceeding the value of comparable goods.

In economics, a common-pool resource (CPR) is a type of good consisting of a natural or human-made resource system, whose size or characteristics makes it costly, but not impossible, to exclude potential beneficiaries from obtaining benefits from its use. Unlike pure public goods, common pool resources face problems of congestion or overuse, because they are subtractable. A common-pool resource typically consists of a core resource, which defines the stock variable, while providing a limited quantity of extractable fringe units, which defines the flow variable. While the core resource is to be protected or nurtured in order to allow for its continuous exploitation, the fringe units can be harvested or consumed.

In economics, a good, service or resource are broadly assigned two fundamental characteristics; a degree of excludability and a degree of rivalry. Excludability is defined as the degree to which a good, service or resource can be limited to only paying customers, or conversely, the degree to which a supplier, producer or other managing body can prevent "free" consumption of a good.

Common goods are defined in economics as goods that are rivalrous and non-excludable. Thus, they constitute one of the four main types based on the criteria:

“Anti-rival good” is a neologism suggested by Steven Weber. According to his definition, it is the opposite of a rival good. The more people share an anti-rival good, the more utility each person receives. Examples include software and other information goods created through the process of commons-based peer production.

Property rights are constructs in economics for determining how a resource or economic good is used and owned, which have developed over ancient and modern history, from Abrahamic law to Article 17 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Resources can be owned by individuals, associations, collectives, or governments.

Public economics(or economics of the public sector) is the study of government policy through the lens of economic efficiency and equity. Public economics builds on the theory of welfare economics and is ultimately used as a tool to improve social welfare. Welfare can be defined in terms of well-being, prosperity, and overall state of being.

Several theories of taxation exist in public economics. Governments at all levels need to raise revenue from a variety of sources to finance public-sector expenditures.

This glossary of economics is a list of definitions of terms and concepts used in economics, its sub-disciplines, and related fields.