Alan Mathison Turing was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher and theoretical biologist. He was highly influential in the development of theoretical computer science, providing a formalisation of the concepts of algorithm and computation with the Turing machine, which can be considered a model of a general-purpose computer. Turing is widely considered to be the father of theoretical computer science.

Bletchley Park is an English country house and estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes (Buckinghamshire), that became the principal centre of Allied code-breaking during the Second World War. The mansion was constructed during the years following 1883 for the financier and politician Herbert Leon in the Victorian Gothic, Tudor and Dutch Baroque styles, on the site of older buildings of the same name.

Colossus was a set of computers developed by British codebreakers in the years 1943–1945 to help in the cryptanalysis of the Lorenz cipher. Colossus used thermionic valves to perform Boolean and counting operations. Colossus is thus regarded as the world's first programmable, electronic, digital computer, although it was programmed by switches and plugs and not by a stored program.

Brigadier John Hessell Tiltman, was a British Army officer who worked in intelligence, often at or with the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) starting in the 1920s. His intelligence work was largely connected with cryptography, and he showed exceptional skill at cryptanalysis. His work in association with Bill Tutte on the cryptanalysis of the Lorenz cipher, the German teleprinter cipher, called "Tunny" at Bletchley Park, led to breakthroughs in attack methods on the code, without a computer. It was to exploit those methods, at extremely high speed with great reliability, that Colossus, the first digital programmable electronic computer, was designed and built.

Thomas Harold Flowers MBE was an English engineer with the British General Post Office. During World War II, Flowers designed and built Colossus, the world's first programmable electronic computer, to help decipher encrypted German messages.

Enigma is a 2001 espionage thriller film directed by Michael Apted from a screenplay by Tom Stoppard. The script was adapted from the 1995 novel Enigma by Robert Harris, about the Enigma codebreakers of Bletchley Park in the Second World War.

Commander Alexander "Alastair" Guthrie Denniston was a Scottish codebreaker in Room 40, deputy head of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) and hockey player. Denniston was appointed operational head of GC&CS in 1919 and remained so until February 1942.

Conel Hugh O'Donel Alexander, known as Hugh Alexander and C. H. O'D. Alexander, was an Irish-born British cryptanalyst, chess player, and chess writer. He worked on the German Enigma machine at Bletchley Park during the Second World War, and was later the head of the cryptanalysis division at GCHQ for 25 years. He was twice British chess champion and earned the title of International Master.

Edward Hugh Simpson CB was a British codebreaker, statistician and civil servant. He was best known for having described Simpson's paradox along with Udny Yule.

John Robert Fisher Jeffreys was a British mathematician and World War II codebreaker.

Rolf Noskwith was a British businessman who during the Second World War worked under Alan Turing as a cryptographer at the Bletchley Park British military base.

The Alan Turing Year, 2012, marked the celebration of the life and scientific influence of Alan Turing during the centenary of his birth on 23 June 1912. Turing had an important influence on computing, computer science, artificial intelligence, developmental biology, and the mathematical theory of computability and made important contributions to code-breaking during the Second World War. The Alan Turing Centenary Advisory committee (TCAC) was originally set up by Professor Barry Cooper

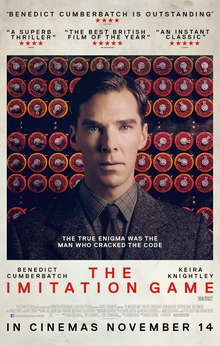

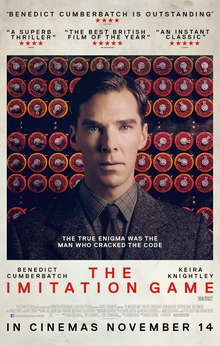

The Imitation Game is a 2014 American period biographical thriller film directed by Morten Tyldum and written by Graham Moore, based on the 1983 biography Alan Turing: The Enigma by Andrew Hodges.

About 7,500 women worked in Bletchley Park, the central site for British cryptanalysts during World War II. Women constituted roughly 75% of the workforce there. While women were overwhelmingly under-represented in high-level work such as cryptanalysis, they were employed in large numbers in other important areas, including as operators of cryptographic and communications machinery, translators of Axis documents, traffic analysts, clerical workers, and more. Women made up the majority of Bletchley Park’s workforce, most enlisted in the Women’s Royal Naval Service, WRNS, nicknamed the Wrens.

The Turing Guide, written by Jack Copeland, Jonathan Bowen, Mark Sprevak, Robin Wilson, and others and published in 2017, is a book about the work and life of the British mathematician, philosopher, and early computer scientist, Alan Turing (1912–1954).

Sir John Dermot Turing, 12th Baronet is a British solicitor and author.

Turochamp is a chess program developed by Alan Turing and David Champernowne in 1948. It was created as part of research by the pair into computer science and machine learning. Turochamp is capable of playing an entire chess game against a human player at a low level of play by calculating all potential moves and all potential player moves in response, as well as some further moves it deems considerable. It then assigns point values to each game state, and selects the move resulting in the highest point value.

Behind the Enigma: The Authorised History of GCHQ, Britain's Secret Cyber-Intelligence Agency is an authorised history of GCHQ, written by intelligence and security expert John Ferris. It was published on 20 October 2020 by Bloomsbury Publishing.