Related Research Articles

In music, a fugue is a contrapuntal compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject that is introduced at the beginning in imitation and which recurs frequently in the course of the composition. It is not to be confused with a fuguing tune, which is a style of song popularized by and mostly limited to early American music and West Gallery music. A fugue usually has three main sections: an exposition, a development and a final entry that contains the return of the subject in the fugue's tonic key. Some fugues have a recapitulation.

Sonata, in music, literally means a piece played as opposed to a cantata, a piece sung. The term evolved through the history of music, designating a variety of forms until the Classical era, when it took on increasing importance. Sonata is a vague term, with varying meanings depending on the context and time period. By the early 19th century, it came to represent a principle of composing large-scale works. It was applied to most instrumental genres and regarded—alongside the fugue—as one of two fundamental methods of organizing, interpreting and analyzing concert music. Though the musical style of sonatas has changed since the Classical era, most 20th- and 21st-century sonatas still maintain the same structure.

Sonata form is a musical structure generally consisting of three main sections: an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation. It has been used widely since the middle of the 18th century.

In music, modulation is the change from one tonality to another. This may or may not be accompanied by a change in key signature. Modulations articulate or create the structure or form of many pieces, as well as add interest. Treatment of a chord as the tonic for less than a phrase is considered tonicization.

Modulation is the essential part of the art. Without it there is little music, for a piece derives its true beauty not from the large number of fixed modes which it embraces but rather from the subtle fabric of its modulation.

The Piano Quintet in E-flat major, Op. 44, by Robert Schumann was composed in 1842 and received its first public performance the following year. Noted for its "extroverted, exuberant" character, Schumann's piano quintet is considered one of his finest compositions and a major work of nineteenth-century chamber music. Composed for piano and string quartet, the work revolutionized the instrumentation and musical character of the piano quintet and established it as a quintessentially Romantic genre.

In Western musical theory, a cadence is the end of a phrase in which the melody or harmony creates a sense of full or partial resolution, especially in music of the 16th century onwards. A harmonic cadence is a progression of two or more chords that concludes a phrase, section, or piece of music. A rhythmic cadence is a characteristic rhythmic pattern that indicates the end of a phrase. A cadence can be labeled "weak" or "strong" depending on the impression of finality it gives. While cadences are usually classified by specific chord or melodic progressions, the use of such progressions does not necessarily constitute a cadence—there must be a sense of closure, as at the end of a phrase. Harmonic rhythm plays an important part in determining where a cadence occurs.

Ludwig van Beethoven's String Quartet No. 11 in F minor, Op. 95, from 1810, was his last before his late string quartets. It is commonly referred to as the "Serioso," stemming from his title "Quartett[o] Serioso" at the beginning and the tempo designation for the third movement.

Sonata form is one of the most influential ideas in the history of Western classical music. Since the establishment of the practice by composers like C.P.E. Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert and the codification of this practice into teaching and theory, the practice of writing works in sonata form has changed considerably.

E major is a major scale based on E, consisting of the pitches E, F♯, G♯, A, B, C♯, and D♯. Its key signature has four sharps. Its relative minor is C-sharp minor and its parallel minor is E minor. Its enharmonic equivalent, F-flat major, has six flats and the double-flat B, which makes it impractical to use.

The String Quartet No. 15 in A minor, Op. 132, by Ludwig van Beethoven, was written in 1825, given its public premiere on November 6 of that year by the Schuppanzigh Quartet and was dedicated to Count Nikolai Galitzin, as were Opp. 127 and 130. The number traditionally assigned to it is based on the order of its publication; it is actually the thirteenth quartet in order of composition.

G major is a major scale based on G, with the pitches G, A, B, C, D, E, and F♯. Its key signature has one sharp. Its relative minor is E minor and its parallel minor is G minor.

The Symphony No. 6 in A major, WAB 106, by Austrian composer Anton Bruckner (1824–1896) is a work in four movements composed between September 24, 1879 and September 3, 1881 and dedicated to his landlord, Anton van Ölzelt-Newin. Only two movements from it were performed in public in the composer's lifetime. Though it possesses many characteristic features of a Bruckner symphony, it differs the most from the rest of his symphonic repertory. Redlich went so far as to cite the lack of hallmarks of Bruckner's symphonic compositional style in the Sixth Symphony for the somewhat bewildered reaction of supporters and critics alike.

D minor is a minor scale based on D, consisting of the pitches D, E, F, G, A, B♭, and C. Its key signature has one flat. Its relative major is F major and its parallel major is D major.

A-flat minor is a minor scale based on A♭, consisting of the pitches A♭, B♭, C♭, D♭, E♭, F♭, and G♭. Its key signature has seven flats. Its relative major is C-flat major, its parallel major is A-flat major, and its enharmonic equivalent is G-sharp minor.

The Piano Sonata No. 3 in F minor, Op. 5 of Johannes Brahms was written in 1853 and published the following year. The sonata is unusually large, consisting of five movements, as opposed to the traditional three or four. When he wrote this piano sonata, the genre was seen by many to be past its heyday. Brahms, enamored of Beethoven and the classical style, composed Piano Sonata No. 3 with a masterful combination of free Romantic spirit and strict classical architecture. As a further testament to Brahms' affinity for Beethoven, the Piano Sonata is infused with the instantly recognizable motive from Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 during the first, third, and fourth movements. Composed in Düsseldorf, it marks the end of his cycle of three sonatas, and was presented to Robert Schumann in November of that year; it was the last work that Brahms submitted to Schumann for commentary. Brahms was barely 20 years old at its composition. The piece is dedicated to Countess Ida von Hohenthal of Leipzig.

Sergei Prokofiev's Piano Sonata No. 8 in B♭ major, Op. 84 is a sonata for solo piano, the third and longest of the three "war sonatas", with performances typically lasting around 30 minutes. He completed it in 1944 and dedicated it to his partner Mira Mendelson, who later became his second wife. The sonata was first performed on 30 December 1944, in Moscow, by Emil Gilels.

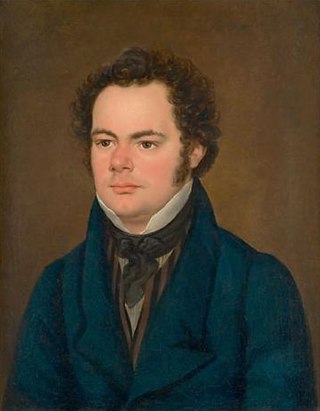

Franz Schubert's last three piano sonatas, D 958, 959 and 960, are his last major compositions for solo piano. They were written during the last months of his life, between the spring and autumn of 1828, but were not published until about ten years after his death, in 1838–39. Like the rest of Schubert's piano sonatas, they were mostly neglected in the 19th century. By the late 20th century, however, public and critical opinion had changed, and these sonatas are now considered among the most important of the composer's mature masterpieces. They are part of the core piano repertoire, appearing regularly on concert programs and recordings.

Homotonal (same-tonality) is a technical musical term pertaining to the tonal structure of multi-movement compositions. It was introduced into musicology by Hans Keller. According to Keller's definition and usage, a multi-movement composition is 'homotonal' if all of its movements have the same tonic (keynote).

The Piano Quartet No. 3 in C minor, Op. 60, completed by Johannes Brahms in 1875, is scored for piano, violin, viola and cello. It is sometimes called the Werther Quartet after Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther. The premiere took place in Vienna on November 18th 1875 to an anxious public. Richard Wagner and his wife Cosima were in attendance.

References

- ↑ Gordon Cameron Sly, ed. (2009). Keys to the Drama: Nine Perspectives on Sonata Forms, p.67. ISBN 9780754694601.

- 1 2 William Kinderman and Harald Krebs, eds. (1996). The Second Practice of Nineteenth-Century Tonality, p.9. ISBN 9780803227248.

- ↑ "When his father told him it was customary to start and finish in the same key, Ives said that was as silly as having to die in the same house you were born in." Paul Moor, "On Horseback to Heaven: Charles Ives", pp. 410-411, in James Peter Burkholder, ed., Charles Ives and His World, Princeton U. Press, (1996). ISBN 0-691-01164-8

- ↑ Radice, Mark A. (2012). Chamber Music: An Essential History. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472051656 . Retrieved 2014-08-10.

- ↑ Adrienne Fried Block (2000). Amy Beach, Passionate Victorian: The Life and Work of an American Composer, 1867-1944, p.375 n.18. ISBN 9780195137842.

- ↑ Block (2000), p.268.

- ↑ Mitchell (1980), p.265, n.160.

- ↑ Mitchell, Donald (1980). Gustav Mahler: The Early Years, p.221. ISBN 9780520041417.

- ↑ "Sonata for Violin and Cello (Ravel, Maurice) - IMSLP/Petrucci Music Library: Free Public Domain Sheet Music". imslp.org. Retrieved 2019-07-01.