The Puebloans, or Pueblo peoples, are Native Americans in the Southwestern United States who share common agricultural, material, and religious practices. Among the currently inhabited Pueblos, Taos, San Ildefonso, Acoma, Zuni, and Hopi are some of the most commonly known. Pueblo people speak languages from four different language families, and each Pueblo is further divided culturally by kinship systems and agricultural practices, although all cultivate varieties of corn (maize).

The Hopi are Native Americans who primarily live in northeastern Arizona. The majority are enrolled in the Hopi Tribe of Arizona and live on the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona; however, some Hopi people are enrolled in the Colorado River Indian Tribes of the Colorado River Indian Reservation at the border of Arizona and California.

A kachina is a spirit being in the religious beliefs of the Pueblo people, Native American cultures located in the south-western part of the United States. In the Pueblo cultures, kachina rites are practiced by the Hopi, Hopi-Tewa and Zuni peoples and certain Keresan tribes, as well as in most Pueblo tribes in New Mexico.

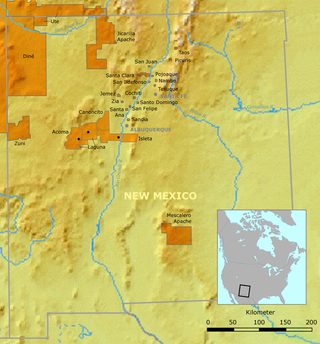

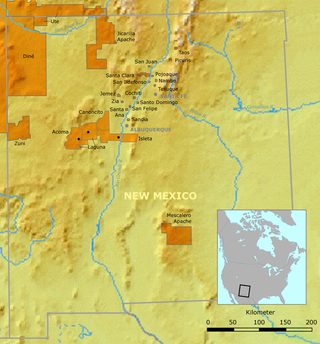

The Zuni are Native American Pueblo peoples native to the Zuni River valley. The Zuni people today are federally recognized as the Zuni Tribe of the Zuni Reservation, New Mexico, and most live in the Pueblo of Zuni on the Zuni River, a tributary of the Little Colorado River, in western New Mexico, United States. The Pueblo of Zuni is 55 km (34 mi) south of Gallup, New Mexico. The Zuni tribe lived in multi level adobe houses. In addition to the reservation, the tribe owns trust lands in Catron County, New Mexico, and Apache County, Arizona. The Zuni call their homeland Halona Idiwan’a or Middle Place. The word Zuni is believed to derive from the Western Keres language (Acoma) word sɨ̂‧ni, or a cognate thereof.

A kiva is a space used by Puebloans for rites and political meetings, many of them associated with the kachina belief system. Among the modern Hopi and most other Pueblo peoples, "kiva" means a large room that is circular and underground, and used for spiritual ceremonies and a place of worship.

The Tewa are a linguistic group of Pueblo Native Americans who speak the Tewa language and share the Pueblo culture. Their homelands are on or near the Rio Grande in New Mexico north of Santa Fe. They comprise the following communities:

Jesse Walter Fewkes was an American anthropologist, archaeologist, writer, and naturalist.

Clown society is a term used in anthropology and sociology for an organization of comedic entertainers who have a formalized role in a culture or society.

Oasisamerica is a cultural region of Indigenous peoples in North America. Their precontact cultures were predominantly agrarian, in contrast with neighboring tribes to the south in Aridoamerica. The region spans parts of Northwestern Mexico and Southwestern United States and can include most of Arizona and New Mexico; southern parts of Utah and Colorado; and northern parts of Sonora and Chihuahua. During some historical periods, it might have included parts of California and Texas as well.

Frederick Russell Eggan was an American anthropologist best known for his innovative application of the principles of British social anthropology to the study of Native American tribes. He was the favorite student of the British social anthropologist A. R. Radcliffe-Brown during Radcliffe-Brown's years at the University of Chicago. His fieldwork was among Pueblo peoples in the southwestern U.S. Eggan later taught at Chicago himself. His students there included Sol Tax.

Hopi katsina figures, also known as kachina dolls, are figures carved, typically from cottonwood root, by Hopi people to instruct young girls and new brides about katsinas or katsinam, the immortal beings that bring rain, control other aspects of the natural world and society, and act as messengers between humans and the spirit world.

Elsie Worthington Clews Parsons was an American anthropologist, sociologist, folklorist, and feminist who studied Native American tribes—such as the Tewa and Hopi—in Arizona, New Mexico, and Mexico. She helped found The New School. She was associate editor for The Journal of American Folklore (1918–1941), president of the American Folklore Society (1919–1920), president of the American Ethnological Society (1923–1925), and was elected the first female president of the American Anthropological Association (1941) right before her death.

The Awatovi Ruins, spelled Awat'ovi in recent literature, are an archaeological site on the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona, United States. The site contains the ruins of a pueblo estimated to be 500 years old, as well as those of a 17th-century Spanish mission. It was visited in the 16th century by members of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado's exploratory expedition. In the 1930s, Hopi artist Fred Kabotie was commissioned by the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of Harvard University to reproduce the prehistoric murals found during the excavation of the Awatovi Ruins. The site was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964.

The Koshare Indian Museum is an art and scouting museum in La Junta, Colorado. The building, located on the Otero Junior College campus, is a tri-level museum with an attached kiva that is built with the largest self-supporting log roof in the world. The building was built in 1949.

The Pueblo IV Period was the fourth period of ancient pueblo life in the American Southwest. At the end of prior Pueblo III Period, Ancestral Puebloans living in the Colorado and Utah regions abandoned their settlements and migrated south to the Pecos River and Rio Grande valleys. As a result, pueblos in those areas saw a significant increase in total population.

Ritual clowns, also known as sacred clowns, are a characteristic feature of the ritual life of many traditional religions, and they typically employ scatology and obscenities. Ritual clowning is where comedy and satire originated; in Ancient Greece, ritual clowning, phallic processions and ritual aischrologia found their literary form in the plays of Aristophanes.

Art of the American Southwest is the visual arts of the Southwestern United States. This region encompasses Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of California, Colorado, Nevada, Texas, and Utah. These arts include architecture, ceramics, drawing, filmmaking, painting, photography, sculpture, printmaking, and other media, ranging from the ancient past to the contemporary arts of the present day.

Bertha Pauline Dutton was an American anthropologist and ethnologist specializing in the American Southwest and Mesoamerica. She was one of the first female archeologists to work with the National Park Service.

Pueblo pottery are ceramic objects made by the Indigenous Pueblo people and their antecedents, the Ancestral Puebloans and Mogollon cultures in the Southwestern United States and Northern Mexico. For centuries, pottery has been central to pueblo life as a feature of ceremonial and utilitarian usage. The clay is locally sourced, most frequently handmade, and fired traditionally in an earthen pit. These items take the form of storage jars, canteens, serving bowls, seed jars, and ladles. Some utility wares were undecorated except from simple corrugations or marks made with a stick or fingernail, however many examples for centuries were painted with abstract or representational motifs. Some pueblos made effigy vessels, fetishes or figurines. During modern times, pueblo pottery was produced specifically as an art form to serve an economic function. This role is not dissimilar to prehistoric times when pottery was traded throughout the Southwest, and in historic times after contact with the Spanish colonialists.

Pueblo religion is the religion of the Puebloans, a group of Native American tribes in the Southwestern United States. It is deeply intertwined with their culture and daily life. The Puebloans practice a spirituality focused on maintaining balance between the physical and spiritual worlds, which they believe is essential for bringing rain, ensuring good crops, and promoting well-being.