In Greek mythology, Agamemnon was a king of Mycenae who commanded the Achaeans during the Trojan War. He was the son of King Atreus and Queen Aerope, the brother of Menelaus, the husband of Clytemnestra, and the father of Iphigenia, Iphianassa, Electra, Laodike, Orestes and Chrysothemis. Legends make him the king of Mycenae or Argos, thought to be different names for the same area. Agamemnon was killed upon his return from Troy by Clytemnestra, or in an older version of the story, by Clytemnestra's lover Aegisthus.

Aegisthus was a figure in Greek mythology. Aegisthus is known from two primary sources: the first is Homer's Odyssey, believed to have been first written down by Homer at the end of the 8th century BC, and the second from Aeschylus's Oresteia, written in the 5th century BC. Aegisthus also features heavily in the action of Euripides's Electra, although his character remains offstage.

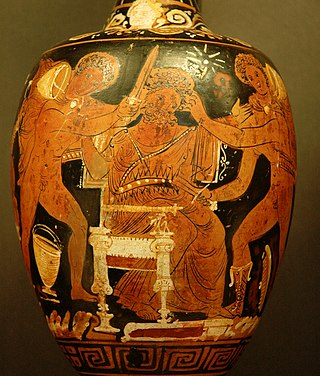

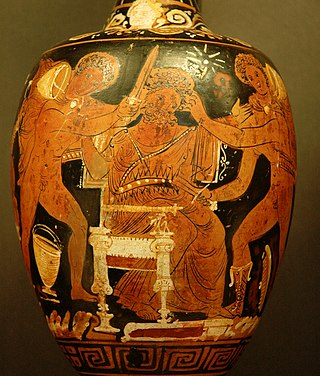

In Greek mythology, Menelaus was a Greek king of Mycenaean (pre-Dorian) Sparta. According to the Iliad, the Trojan war began as a result of Menelaus's wife, Helen, fleeing to Troy with the Trojan prince Paris. Menelaus was a central figure in the Trojan War, leading the Spartan contingent of the Greek army, under his elder brother Agamemnon, king of Mycenae. Prominent in both the Iliad and Odyssey, Menelaus was also popular in Greek vase painting and Greek tragedy, the latter more as a hero of the Trojan War than as a member of the doomed House of Atreus.

In Greek mythology, Orestes or Orestis was the son of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon, and the brother of Electra. He is the subject of several Ancient Greek plays and of various myths connected with his madness, revenge, and purification, which retain obscure threads of much older works. In particular Orestes plays a main role in Aeschylus' Oresteia.

In Greek mythology, Iphigenia was a daughter of King Agamemnon and Queen Clytemnestra, and thus a princess of Mycenae.

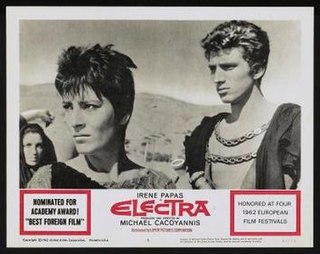

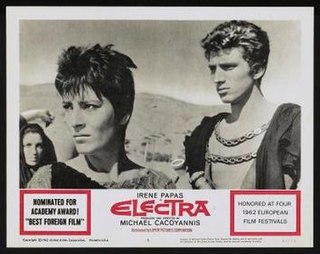

Electra, also spelt Elektra, is one of the most popular mythological characters in tragedies. She is the main character in two Greek tragedies, Electra by Sophocles and Electra by Euripides. She is also the central figure in plays by Aeschylus, Alfieri, Voltaire, Hofmannsthal, and Eugene O'Neill. She is a vengeful soul in The Libation Bearers, the second play of Aeschylus' Oresteia trilogy. She plans out an attack with her brother to kill their mother, Clytemnestra.

In Greek mythology, Strophius was the name of the following personages:

In Greek mythology, Atreus was a king of Mycenae in the Peloponnese, the son of Pelops and Hippodamia, and the father of Agamemnon and Menelaus. Collectively, his descendants are known as Atreidai or Atreidae.

The Oresteia is a trilogy of Greek tragedies written by Aeschylus in the 5th century BCE, concerning the murder of Agamemnon by Clytemnestra, the murder of Clytemnestra by Orestes, the trial of Orestes, the end of the curse on the House of Atreus and the pacification of the Furies.

Electra is a 1962 Greek film based on the play Electra, written by Euripides. It was directed by Michael Cacoyannis, serving as the first installment of his "Greek tragedy" trilogy, followed by The Trojan Women in 1971 and Iphigenia in 1977. The film starred Irene Papas in the lead role as Elektra and Giannis Fertis as Orestis.

Electra, also Elektra or The Electra, is a Greek tragedy by Sophocles. Its date is not known, but various stylistic similarities with the Philoctetes and the Oedipus at Colonus lead scholars to suppose that it was written towards the end of Sophocles' career. Jebb dates it between 420 BC and 414 BC.

Iphigenia in Aulis or Iphigenia at Aulis is the last of the extant works by the playwright Euripides. Written between 408, after Orestes, and 406 BC, the year of Euripides' death, the play was first produced the following year in a trilogy with The Bacchae and Alcmaeon in Corinth by his son or nephew, Euripides the Younger, and won first place at the City Dionysia in Athens.

Iphigenia in Tauris is a drama by the playwright Euripides, written between 414 BC and 412 BC. It has much in common with another of Euripides's plays, Helen, as well as the lost play Andromeda, and is often described as a romance, a melodrama, a tragi-comedy or an escape play.

Euripides' Electra is a play probably written in the mid 410s BC, likely before 413 BC. It is unclear whether it was first produced before or after Sophocles' version of the Electra story.

Iphigenia in Tauris is a reworking by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe of the ancient Greek tragedy Ἰφιγένεια ἐν Ταύροις by Euripides. Euripides' title means "Iphigenia among the Taurians", whereas Goethe's title means "Iphigenia in Taurica", the country of the Tauri.

Orestes (408 BCE) is an Ancient Greek play by Euripides that follows the events of Orestes after he had murdered his mother.

Iphigenia is a 1977 Greek film directed by Michael Cacoyannis, based on the Greek myth of Iphigenia, the daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, who was ordered by the goddess Artemis to be sacrificed. Cacoyannis adapted the film, the third in his "Greek Tragedy" trilogy, from his stage production of Euripides' play Iphigenia at Aulis. The film stars Tatiana Papamoschou as Iphigenia, Kostas Kazakos as Agamemnon and Irene Papas as Clytemnestra. The score was composed by Mikis Theodorakis.

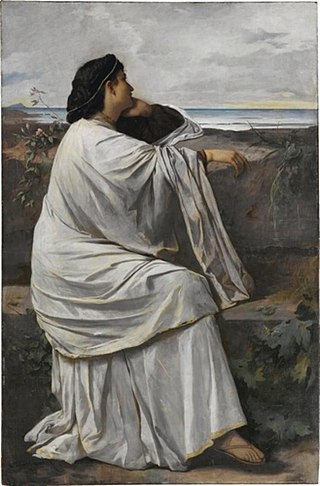

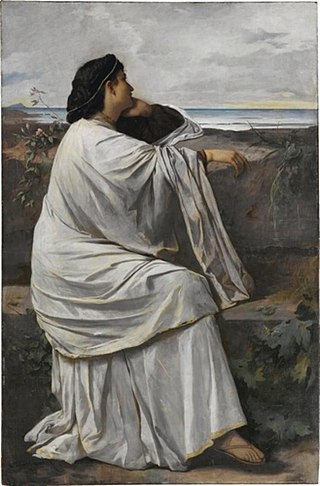

Clytemnestra, in Greek mythology, was the wife of Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, and the half-sister of Helen of Troy. In Aeschylus' Oresteia, she murders Agamemnon – said by Euripides to be her second husband – and the Trojan princess Cassandra, whom Agamemnon had taken as a war prize following the sack of Troy; however, in Homer's Odyssey, her role in Agamemnon's death is unclear and her character is significantly more subdued.

Agamemnon is a fabula crepidata of c. 1012 lines of verse written by Lucius Annaeus Seneca in the first century AD, which tells the story of Agamemnon, who was killed by his wife Clytemnestra in his palace after his return from Troy.

Iphigenia was the daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra. According to the story, Agamemnon committed a mistake and had to sacrifice Iphigenia to Artemis to appease her. There are different versions of the story. According to one side of the story, before Agamemnon could sacrifice her, Artemis saved her and replaced her with a deer on the altar. In the other version, Agamemnon actually went through with the sacrifice. The different versions aid in the different depictions of Iphigenia.