Unless otherwise noted, statements in this article refer to Standard Finnish, which is based on the dialect spoken in the former Häme Province in central south Finland. Standard Finnish is used by professional speakers, such as reporters and news presenters on television.

The phonology of the open back vowels of the English language has undergone changes both overall and with regional variations, through Old and Middle English to the present. The sounds heard in modern English were significantly influenced by the Great Vowel Shift, as well as more recent developments in some dialects such as the cot–caught merger.

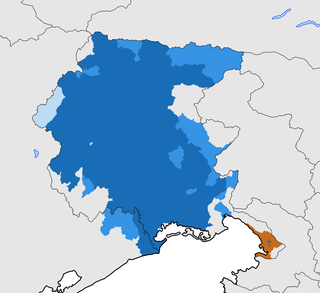

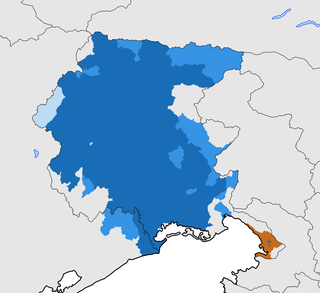

Friulian or Friulan is a Romance language belonging to the Rhaeto-Romance family, spoken in the Friuli region of northeastern Italy. Friulian has around 600,000 speakers, the vast majority of whom also speak Italian. It is sometimes called Eastern Ladin since it shares the same roots as Ladin, but over the centuries, it has diverged under the influence of surrounding languages, including German, Italian, Venetian, and Slovene. Documents in Friulian are attested from the 11th century and poetry and literature date as far back as 1300. By the 20th century, there was a revival of interest in the language.

Belgian French is the variety of French spoken mainly among the French Community of Belgium, alongside related Oïl languages of the region such as Walloon, Picard, Champenois, and Lorrain (Gaumais). The French language spoken in Belgium differs very little from that of France or Switzerland. It is characterized by the use of some terms that are considered archaic in France, as well as loanwords from languages such as Walloon, Picard, and Belgian Dutch.

Portuguese dialects are the mutually intelligible variations of the Portuguese language in Portuguese-speaking countries and other areas holding some degree of cultural bond with the language. Portuguese has two standard forms of writing and numerous regional spoken variations, with often large phonological and lexical differences.

The phonology of Portuguese varies among dialects, in extreme cases leading to some difficulties in mutual intelligibility. This article on phonology focuses on the pronunciations that are generally regarded as standard. Since Portuguese is a pluricentric language, and differences between European Portuguese (EP), Brazilian Portuguese (BP), and Angolan Portuguese (AP) can be considerable, varieties are distinguished whenever necessary.

While many languages have numerous dialects that differ in phonology, contemporary spoken Arabic is more properly described as a continuum of varieties. This article deals primarily with Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), which is the standard variety shared by educated speakers throughout Arabic-speaking regions. MSA is used in writing in formal print media and orally in newscasts, speeches and formal declarations of numerous types.

English phonology is the system of speech sounds used in spoken English. Like many other languages, English has wide variation in pronunciation, both historically and from dialect to dialect. In general, however, the regional dialects of English share a largely similar phonological system. Among other things, most dialects have vowel reduction in unstressed syllables and a complex set of phonological features that distinguish fortis and lenis consonants.

In phonology, epenthesis means the addition of one or more sounds to a word, especially in the beginning syllable (prothesis) or in the ending syllable (paragoge) or in-between two syllabic sounds in a word. The word epenthesis comes from epi-'in addition to' and en-'in' and thesis'putting'. Epenthesis may be divided into two types: excrescence for the addition of a consonant, and for the addition of a vowel, svarabhakti or alternatively anaptyxis. The opposite process, where one or more sounds are removed, is referred to as elision.

French phonology is the sound system of French. This article discusses mainly the phonology of all the varieties of Standard French. Notable phonological features include its uvular r, nasal vowels, and three processes affecting word-final sounds:

The sound system of Norwegian resembles that of Swedish. There is considerable variation among the dialects, and all pronunciations are considered by official policy to be equally correct – there is no official spoken standard, although it can be said that Eastern Norwegian Bokmål speech has an unofficial spoken standard, called Urban East Norwegian or Standard East Norwegian, loosely based on the speech of the literate classes of the Oslo area. This variant is the most common one taught to foreign students.

In an alphabetic writing system, a silent letter is a letter that, in a particular word, does not correspond to any sound in the word's pronunciation. In linguistics, a silent letter is often symbolised with a null sign U+2205∅EMPTY SET. Null is an unpronounced or unwritten segment. The symbol resembles the Scandinavian letter Ø and other symbols.

The phonology of the Persian language varies between regional dialects, standard varieties, and even from older variates of Persian. Persian is a pluricentric language and countries that have Persian as an official language have separate standard varieties, namely: Standard Dari (Afghanistan), Standard Iranian Persian (Iran) and Standard Tajik (Tajikistan). The most significant differences between standard varieties of Persian are their vowel systems. Standard varieties of Persian have anywhere from 6 to 8 vowel distinctions, and similar vowels may be pronounced differently between standards. However, there are not many notable differences when comparing consonants, as all standard varieties a similar amount of consonant sounds. Though, colloquial varieties generally have more differences than their standard counterparts. Most dialects feature contrastive stress and syllable-final consonant clusters. Linguists tend to focus on Iranian Persian, so this article may contain less adequate information regarding other varieties.

L-vocalization, in linguistics, is a process by which a lateral approximant sound such as, or, perhaps more often, velarized, is replaced by a vowel or a semivowel.

The phonology of Quebec French is more complex than that of Parisian or Continental French. Quebec French has maintained phonemic distinctions between and, and, and, and. The latter phoneme of each pair has disappeared in Parisian French, and only the last distinction has been maintained in Meridional French, yet all of these distinctions persist in Swiss and Belgian French.

Portuguese orthography is based on the Latin alphabet and makes use of the acute accent, the circumflex accent, the grave accent, the tilde, and the cedilla to denote stress, vowel height, nasalization, and other sound changes. The diaeresis was abolished by the last Orthography Agreement. Accented letters and digraphs are not counted as separate characters for collation purposes.

The phonology of Bengali, like that of its neighbouring Eastern Indo-Aryan languages, is characterised by a wide variety of diphthongs and inherent back vowels.

One of the dialects of the Maltese language is the Żejtun dialect. This dialect is used by many of the inhabitants of Żejtun and in other settlements around this city such as Marsaxlokk, and spoken by about 12,000 people.

The small group of Hachijō dialects, natively called Shima Kotoba, depending on classification, either are the most divergent form of Japanese, or comprise a branch of Japonic. Hachijō is currently spoken on two of the Izu Islands south of Tokyo as well as on the Daitō Islands of Okinawa Prefecture, which were settled from Hachijō-jima in the Meiji period. It was also previously spoken on the island of Hachijō-kojima, which is now abandoned. Based on the criterion of mutual intelligibility, Hachijō may be considered a distinct Japonic language, rather than a dialect of Japanese.

This article is about the phonology of Egyptian Arabic, also known as Cairene Arabic or Masri. It deals with the phonology and phonetics of Egyptian Arabic as well as the phonological development of child native speakers of the dialect. To varying degrees, it affects the pronunciation of Literary Arabic by native Egyptian Arabic speakers, as is the case for speakers of all other varieties of Arabic.