Sir Matthew Hale was an influential English barrister, judge and jurist most noted for his treatise Historia Placitorum Coronæ, or The History of the Pleas of the Crown. Born to a barrister and his wife, who had both died by the time he was 5, Hale was raised by his father's relative, a strict Puritan, and inherited his faith. In 1626 he matriculated at Magdalen Hall, Oxford, intending to become a priest, but after a series of distractions was persuaded to become a barrister like his father thanks to an encounter with a Serjeant-at-Law in a dispute over his estate. On 8 November 1628 he joined Lincoln's Inn, where he was called to the Bar on 17 May 1636. As a barrister, Hale represented a variety of Royalist figures during the prelude and duration of the English Civil War, including Thomas Wentworth and William Laud; it has been hypothesised that Hale was to represent Charles I at his state trial, and conceived the defence Charles used. Despite the Royalist loss, Hale's reputation for integrity and his political neutrality saved him from any repercussions, and under the Commonwealth of England he was made Chairman of the Hale Commission, which investigated law reform. Following the Commission's dissolution, Oliver Cromwell made him a Justice of the Common Pleas.

Sir Edward Coke was an English barrister, judge, and politician who is considered to be the greatest jurist of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras.

William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, PC, SL was a British barrister, politician and judge noted for his reform of English law. Born to Scottish nobility, he was educated in Perth, Scotland, before moving to London at the age of 13 to take up a place at Westminster School. He was accepted into Christ Church, Oxford, in May 1723, and graduated four years later. Returning to London from Oxford, he was called to the Bar by Lincoln's Inn on 23 November 1730, and quickly gained a reputation as an excellent barrister.

Thomas Erskine, 1st Baron Erskine, was a British lawyer and politician. He served as Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain between 1806 and 1807 in the Ministry of All the Talents.

Lloyd Kenyon, 1st Baron Kenyon, was a British politician and barrister, who served as Attorney General, Master of the Rolls and Lord Chief Justice. Born to a country gentleman, he was initially educated in Hanmer before moving to Ruthin School aged 12. Rather than going to university he instead worked as a clerk to an attorney, joining the Middle Temple in 1750 and being called to the Bar in 1756. Initially almost unemployed due to the lack of education and contacts which a university education would have provided, his business increased thanks to his friendships with John Dunning, who, overwhelmed with cases, allowed Kenyon to work many, and Lord Thurlow who secured for him the Chief Justiceship of Chester in 1780. He was returned as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Hindon the same year, serving repeatedly as Attorney General under William Pitt the Younger. He effectively sacrificed his political career in 1784 to challenge the ballot of Charles James Fox, and was rewarded with a baronetcy; from then on he did not speak in the House of Commons, despite remaining an MP.

In law, comity is "a practice among different political entities " involving the "mutual recognition of legislative, executive, and judicial acts."

Edward Bearcroft, KC was an English barrister, judge, and politician.

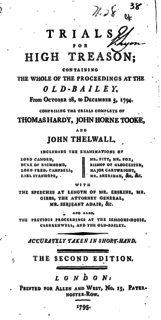

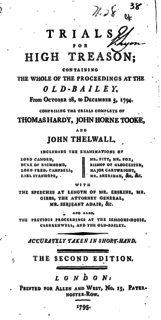

The 1794 Treason Trials, arranged by the administration of William Pitt, were intended to cripple the British radical movement of the 1790s. Over thirty radicals were arrested; three were tried for high treason: Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall. In a repudiation of the government's policies, they were acquitted by three separate juries in November 1794 to public rejoicing. The treason trials were an extension of the sedition trials of 1792 and 1793 against parliamentary reformers in both England and Scotland.

Rear Admiral Sir John Lindsay, was a British naval officer of the 18th century, who achieved the rank of admiral late in his career. Joining the Navy during the Seven Years' War, he served off France, followed by service for several years as captain of a warship stationed in the West Indies. After war's end, he returned to Britain, serving as an MP for Aberdeen Burghs from 1767 to 1768. From August 1769 to March 1772 Lindsay was promoted to commodore and assigned as commander-in-chief of the East Indies Station. He resigned from the Navy for a period following the Battle of Ushant (1778) off the coast of France, during the American War of Independence. In 1784 he was assigned as commodore and commander-in-chief in the Mediterranean. In the last year of his life, he was promoted to rear admiral as an honorary position, as his failing health prevented him from taking a command.

Sir William Garrow was an English barrister, politician and judge known for his indirect reform of the advocacy system, which helped usher in the adversarial court system used in most common law nations today. He introduced the phrase "presumed innocent until proven guilty", insisting that defendants' accusers and their evidence be thoroughly tested in court. Born to a priest and his wife in Monken Hadley, then in Middlesex, Garrow was educated at his father's school in the village before being apprenticed to Thomas Southouse, an attorney in Cheapside, which preceded a pupillage with Mr. Crompton, a special pleader. A dedicated student of the law, Garrow frequently observed cases at the Old Bailey; as a result Crompton recommended that he become a solicitor or barrister. Garrow joined Lincoln's Inn in November 1778, and was called to the Bar on 27 November 1783. He quickly established himself as a criminal defence counsel, and in February 1793 was made a King's Counsel by HM Government to prosecute cases involving treason and felonies.

Sir Richard Aston was an English judge, best known as King's Counsel and Lord Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas in Ireland. Sir Richard Aston was known as one of the early pioneers in Irish Law, in which he sought to change the process in which bills of indictment were issued without the examination of witnesses. In 1765 Sir Aston resigned from his role in Irish law and was subsequently Knighted. Aston died on the 1 March 1778, leaving nothing to either of his surviving wives.

Edward Pennefather PC, KC was an Irish barrister, Law Officer and judge of the Victorian era, who held office as Lord Chief Justice of Ireland.

Thomas Baillie, was an officer of the Royal Navy. He saw service in the Seven Years' War, rising to the rank of captain. He was later appointed to the office of Lieutenant-Governor of Greenwich Hospital, but became involved in the celebrated libel case R v Baillie after he made accusations of mismanagement in the running of the hospital. He was later appointed to the post of Clerk of the Deliveries of the Ordnance, which he held until his death in 1802.

The Trial of Lord George Gordon for high treason occurred on 5 February 1781 before Lord Mansfield in the Court of King's Bench, as a result of Gordon's role in the eponymously named riots. Gordon, President of the Protestant Association, had led a protest against the Papists Act 1778, a Catholic relief bill. Intending only to hand in a petition to Parliament, Gordon riled the crowd by announcing the postponement of the petition, denouncing Members of Parliament and launching "anti-Catholic harangues". The crowd of protesters fragmented and began looting nearby buildings; by the time the riots had finished a week later, 300 had died, and more property had been damaged than during the entire French Revolution. Gordon was almost immediately arrested, and indicted for levying war against the King.

The Case of the Dean of St Asaph, formally R v Shipley, was the 1784 trial of William Davies Shipley, the Dean of St Asaph, for seditious libel. In the aftermath of the American War of Independence, electoral reform had become a substantial issue, and William Pitt the Younger attempted to bring a Bill before Parliament to reform the electoral system. In its support Shipley republished a pamphlet written by his brother-in-law, Sir William Jones, which noted the defects of the existing system and argued in support of Pitt's reforms. Thomas FitzMaurice, the brother of British Prime Minister Earl of Shelburne, reacted by indicting Shipley for seditious libel, a criminal offence which acted as "the government's chief weapon against criticism", since merely publishing something that an individual judge interpreted as libel was enough for a conviction; a jury was prohibited from deciding whether the material was actually libellous. The law was widely seen as unfair, and a Society for Constitutional Information was formed to pay Shipley's legal fees. With financial backing from the society Shipley was able to secure the services of Thomas Erskine KC as his barrister.

William Davies Shipley was an Anglican priest who served as Dean of St Asaph for nearly 52 years, from 27 May 1774 until his death. In a legal cause célèbre which became known as the Case of the Dean of St Asaph, he was tried and convicted on a charge of seditious libel in August 1784, but was discharged by the Court of King's Bench a few months later without being punished.

The trial of Thomas Paine for seditious libel was held on 18 December 1792 in response to his publication of the second part of the Rights of Man. The government of William Pitt, worried by the possibility that the French Revolution might spread to England, had begun suppressing works that espoused radical philosophies.

John Hostettler (1925-2018) was an English writer of legal histories and biographies.

Mary Ann Tocker (1778–1853) was the first woman in Cornwall to be tried for Libel and was celebrated as the first woman to act as her own advocate in a British court of law. She has been referred to as the first woman lawyer. She was seen as a heroine by the radical writers of her day. Her case was widely discussed in the months following her trial in August 1818. She is still referred to today in books on early women radicals as having inspired others with her stand against corruption.